Giacobbe Giusti, ギリシャ彫刻

ウィキペディア、フリー百科事典から。

プラクシテレス 、 ディオニュソスとエルメス 、紀元前4世紀の半分

彫刻は、おそらく最高の’の知られているギリシャの芸術 、これは考古学の大きい数は、例えば、のものに、より現在までに受信に起因する塗装に使用される材料の抵抗が低いです。 しかし、ギリシャの彫刻の出力のごく一部は、私たちに降りてきます。 古代の文献によって記述傑作の多くは、今ひどくバラバラ、失われ、またはのみのコピーを介して知られているローマ時代 以来ルネッサンス 、多くの彫刻はまた時々、オリジナル作品の外観と意味を変えること、現代の芸術家によって復元されました。

インデックス

[ 非表示 ]

使用し、技術と材料

モニュメンタル彫刻

それは戦いに勝利するための記念碑を欠いていたが、ギリシャの芸術は、例えば、主に少なくとも太古の時代に、礼拝のニーズにリンクされていて、その彫刻しました。 偉大な芸術的業績は、教団の委員会や状態によって行われたが、ギリシャの神々にささげか死んとして芸術の構想民間人は、しながら、聖域であっても作品を捧げるために彼らの限られた資源を投資することができます芸術の分野で個人のイニシアティブで東文明は全く不明でした。 類型学の抽象に従って考案された個人の基準偏見にリンクされていないが、彫像は、帰依者の継続的な存在に証言しているクーロスとコレ。 [1]テーマであった、他の分野で人間の姿をしたその同じ神話エジプトとアッシリアの場合と同様に、日常生活や歴史的な戦いの表現の場面では、まれにしか直接神話の物語を通して、主に行われたと。 使用される材料は石(た大理石や石灰岩 )、 ブロンズ 、木材、 粘土など

より多くの古代の石の彫刻では、それらは直接チッピングで実行されました。 使用される機器であったノミ 、ドリルや様々なノミ、マレットで操作すべて。 石のブロックの輸送が問題と高価なので、記念碑的な彫像は、彼らが骨折のリスクを示している場合、彼らは今日まで残っどこに放棄された採石場でのラフな形で切断されたとした。 [2]頭や腕、場合に付着していません本体は、別々に彫刻されて後に混合したペグ小さな部分がセメントで攻撃される可能性がありながら、通常、溶融鉛中に埋め込まれ、金属の石のウェッジ。 これらの彫刻は、常に他のすべてのような驚異的な現実の色の外観を塗装されていたと離れて彫像に着色されているとは異なる材料で作られたアクセサリーを加えて装飾された:目が着色石、ガラスペーストや象牙の一部でした。 金属、ティアラ、イヤリングやネックレスのカール。 槍、剣、手綱やブライドル。 材料はほとんどが失われ、そのうちのサポートの穴に残ってトレースします。

七世紀の作品のサイズの増加BCで、ブロンズ像は、古代からエジプトで実施され、それらを使用した6世紀紀元前の間に広がっていることを融合採石場の技術で製造されるようになりましたにおける技術ロストワックスは棚上げ行列です。 図は、通常のセクションで行われた後者の方法では、モデルではなく、ワックスの木で作られたとの融合のための足跡左湿った砂を充填した容器に撃沈されました。 石像に何が起こったとは対照的に、ブロンズは、自然の色を残したが、私たちが見てきたように、照射さは、他の材料を挿入します。

大きなサイズのテラコッタ像やレリーフがで発見された キプロスで、 エトルリア大理石が不足したシチリア島と南イタリアで、。 最も早い期間陶器片で、それらは、外壁を形成するための粘土のロールで形成されました。焼成時の変形や収縮を防ぐために、粘土、砂、焼成粘土の部分と合わせました。ヘレニズム時代とローマ時代では、金型を使用することがより一般的でした。

二十世紀考古学的発見の唯一の半分は前の過程を明らかにした金と象牙で作られたし 。

小さなプラスチックと「マイナー芸術“

芸術の目的のために小さなギリシャ人は、すでに述べた材料、象牙、骨、金、銀に加えて、使用されます。 切断して絶縁ジョイントされているオブジェクトの多くは、もともとの装飾部品であった三脚 、花瓶、ミラーやその他のツール、およびこれらの場合には、通常、穴がそれを通して、彼らが所属するオブジェクトにリンクされた持っています。他の時間は、彼らが聖域で提供され、吊り下げ用のフックを提示することができます。 溝は神社ドレインに彼らはおそらく彼らはこの日に埋もれたままで、新しい奉納のための部屋を作るために、ぎゅうぎゅう詰めたので、多くの彫像は、私たちに来ています。

小さな金属のオブジェクトは、採石場より少ない労力を要し、固体溶融することにより、主に得られました。 小像は、彼らの拠点で一緒に融合または対応する塩基でそれらを入力することができ、脚の底部にピンを持っていました。 装飾品の製造のためのギリシャ人からの好ましい金属は、銀、金、続いて、異なる合金で青銅でした。 ギリシャ神殿の在庫では、銀と青銅の鍋や調理器具は、常にカタログ表示されますが、最も貴重なオブジェクトは明らかに戦争の戦利品となり、私たちに降りてくるしていません。 聖域での発掘調査は、装飾的なモチーフで、ハーネスや様々な家庭用家具の部品を特に鎧をもたらしたエンボス加工 、落書きやラウンド。打ち出し技法金属箔中のベース上に配置された:使用される技術は異なっていた ビチューメンモデルがで発掘された金型内で逆に殴られた板金をハンマーで、法律で、逆に両方反論した固体パンチの姿貨幣は金属に直接押されました。 切開部を得ることが望まれる設計に応じて形状が変化する器具を用いて行きました。 また、着色石、ガラス、象牙、または他の金属常に多色の効果を得ることを目的とインレイを使用しました。

古代ギリシャで刻まれた宝石は、時には正式ので、それらの使用は、碑文に挙げることができ、シール又は識別マークとして富裕層が使用していました。 第5、第四世紀の寺院の宝物のリストでは、例えば、パルテノン神殿は、宝石を提供間で記憶されます。

ジュエリーの生産のためにギリシャ人によって好ましい材料は、 ‘の川岸に由来し、金であった小アジアで、 トラキアとロシア 。 処理の可能性が多くあった:モデリング、鋳造、打ち出し技法、彫刻、 造粒 、 フィリグリー 、 インレイやノミ 、技術がエジプトやメソポタミアの宝石商によっておそらく学びました。 でも銀は、宝石非常に古風な時代に用いられる金と銀の天然合金広く使用され、電気でした。 このような青銅、鉄、鉛や粘土などの少ない貴重な材料には貴重品を交換するために墓に入れリングやブレスレットに使用しました。 一次情報源は明らかに墓や神社で見つかった作品であるが、他の有用な詳細を提供碑文寺院や発掘調査によって再燃した聖職者の行為の在庫として、。 それはギリシャ本土のような比較的貧しいで古風な、類似したオブジェクトが着用されていなかった場合であっても、金や銀の装飾品、貴重なオブジェクトの慣習儀式申し出ました。 また、古代寺院に多くの場合、宝物を務め、緊急時に溶断することができた貴重品を維持しました。 最初の人間と動物の図は、概略的に表示され、次いで、従来のタイプに応じて、最終的にはより自然に:芸術、ギリシャ人は、様々な期間を通じて変化しても宝石の他の分野と同様に、]組成物は、単純なものから変化するのと同じ方法では時間の経過とともに大きく複雑性を前提としています。 [3]

期間

伝統的にギリシャ彫刻5周期に立ちます:

彫刻は次第にマーク地域の特性を提示:特にで行われたものの、ギリシャ大陸、特にクラシックと古風な作品は、次の世紀に海上貿易の通りを通って広く普及しています。 ヘレニズム時代に作品は、多くの場合、生成され、いくつかの地域の学校の創設と、ローカルで使用します。

起源

バック」に行くプラスチックの幾何学的技術は、人物や動物(馬、牛、鹿、鳥、等)を表す固体キャストの銅像があります。 彼らはアクションで8世紀のBCの数字、グループ、戦士の攻撃と騎兵だけでなく、ミュージシャンや職人の姿に帰属します。 [4]戦士のタイプを再現ブロンズのかなりの数、時には馬や戦車、それはの聖域から来オリンピアし、地域考古学博物館になりました。 [7]で、メトロポリタン美術館 、ニューヨークのではなく、それがゼウスとタイタンの間の闘争を読んで提案されたためにブロンズ群(8世紀の半分BC、H 11 cm)である(基としては人間の姿と図半人半馬):自然の混入は、すでにこの時点で神と秩序の原始敵を示すことになる。 [5]では、ベルリン州立博物館もVIII世紀に属し、馬ですBC、特に、多くの他の類似の例の中で、ほとんどの有機実際モルフォロジーequinaより完全に任意の構造の達成を示している:丸みを帯びた手足、しなやかな身体と関節が指摘[6]以上の作品の中でも代表銅像の重要性アポロまたはアレス 」から来るアテネのアクロポリス (に保存高さ20センチメートルを、 アテネ国立考古学博物館 、広い目をした小さな腰と大きな頭を持つ管状の手足や胴体の三角形と、6613)。 [7]

粘土が広く描いた小さな奉納彫像のためにギリシャ人によって使用されました。 既に一般的なミケーネ時代が、それらは紀元前8世紀から豊富に存在し、粘土が広く利用可能であった世界のギリシャの作品、の定数の一つとなったされています。幾何学様式時代の土器や墓や神社で見つかった次は、同じフォームは同期間内の他の製品をまとめ、解剖学的構造要素にはほとんど関心を示しています。 主に手で成形し、いくつかは、行列によって形成された頭部を持っている、または完全に金型内で行われています。 時には彼らは、ジャーの蓋のハンドルとして、または他の日常のオブジェクトまたは奉納で装飾要素を務めました。 プラスチック粘土プロト幾何学の傑作は、小像形状でケンタウロス のIX世紀、(間に日付の墓で発見され、 の島で) エヴィア 。 馬体が中空円筒横型旋盤を成形し、幾何学的な絵画で装飾されています。 それはケンタウロスで、おそらくブランチまたはツリー、種の典型的な武器を振り回します。 それはカイロン、英雄の賢明な先生(ケンタウロスの右手は6本の指、古代の知恵の符号を有する)である可能性があります。 .彼の左の膝の上にカット、戦いで負ったけが、ヘラクレスが誤って膝カイロンを傷つける伝説への参照を負いません。 彼らはからの幾何学期間の置物に属し ベル状体、長い首とと頭を平坦化:本体はホイールにモデル化したが、図の残りの部分を手で成形し、彼の服は塗装飾り、鳥や他の動物に耐えることができる[9] 。 小さなプラスチック製テラコッタの陶器の他の例は二つのヘッド、戦士である[10]との女性、 ブロンズのアテナイとの類似性を示す、アテネの国立考古学博物館に保存(スパルタ)と芸術の影響の証言しますこの時期のペロポネソスのアテネ。

で象牙彼らは4の墓で見つかった小さなヌード女性像建設された 中旬日付(現在は国立考古学博物館で)アテネで 慎重に彼らは東のモデルからインスピレーションを描画しますが、ソフト成形体を詳細の説明は、背中の毛の鎖のように、技術革新のアテナイである[11] 。

彫刻術で生き生きと自然公演ハード石の上ミケーネ – オン:ギリシャ宝石がまだ原始的とミケーネ文化との関係に関しては、ギャップ、この文明の特徴を反映シール又は識別マークやヴィンテージ幾何として主に役立ちましたギリシャの宝石手作りソープストーンの入札の線画。 粒子の形状は、シリア、または円筒のように、円錐形のドーム型、角と丸みを帯びた可能性があります。 これらは、すべてのスレッドによって中断運ばれる掘削されました。 世紀の間にのみ、彼らは人物、動物、植物を現れ始めるが、常にまとめる形で。 [12]

この期間に属する宝石の比較的いくつかの作品はアッティカ、ペロポネソスや他のギリシャの場所の発掘調査で発見されています。 これは、主に片持ち装飾的な要素を持つ金属ストリップであり、ペンダント元素の形で刻まれた装飾モチーフ、ピンやネックレスで腓骨[13] 。

オリエンタル期間変更 | 編集テキスト ]

この用語は、対象物の輸入とローカル再処理で発生する東と東の影響との関係の強化によって特徴付けられる、幾何以下、ギリシャの期間東方に材料を指し、セラミック彫金から、最終的にすべての症状でギリシャの芸術の新しいコースを出て、そこから技術。 大きな変化の今世紀、紀元前では、彫刻自体は最後の段階、ギリシャの記念碑的芸術の誕生を見ているものです。は熱狂的な最初の東洋の期間、割合のシステムと単一のフォームの新しい概念を置き換えると。

プリニウスはに属性テラコッタ緩和の発明。 彼は最初のレリーフなどの終端タイルで装飾う(。ナットシーッ、最初 のテラコッタは約登場 紀元前にしながら、救援で装飾され、女性の胸像で塗装、 メトープとサイムが描かれました。 は、三角形の同期間に占める空間に装飾を描いたペディメント次の世紀に石で作られたが開始されますプレートを用いて、。 これらのプラスチックの装飾や絵画の例には、主要相、塗装メトープ、職人からのコリント式の作品ですサーモスでアポロ神殿と の聖域 (の両方で の周りに日付、今アテネ国立考古学博物館)、

戦車と馬、農家とプラウ:では、それらはテラコッタの置物を生産し続けています。 ‘の終わりには紀元前8世紀には東からインポート行列の技術を、出演していたし、次の世紀に私たちは特に、成形体の大規模な生産を目撃ゴルテュナ(クレタ島)とコリント。 クレタ島は、多くの粘土板(から来 戦士と女神のイメージで)。 彼らはまた、神話の基であり、最も有名なの間では、クリュタイムネストラとアイギストスによるアガメムノンの殺害(紀元前7世紀の後半、8時間センチ、表現、ゴルテュナでアテナの神殿で見つかった、ある考古学博物館イラクリオン ):シーンは、空間内の数字の巧みな配置を通して素晴らしい劇的な効果で表す。 [14]でもが頻繁にレリーフ装飾を考え出しました。 [15]

キャストレリーフで表現と胸像は中大型船舶に適用された青銅および金属板上の比喩レリーフ大きな神社を飾りました。アート東方の典型的な例は、モンスターや動物のエンボスレリーフが飾らクレタ島で見つかったシールド(約 です。 動物やモンスターのクマの彫刻:ギリシャの様々な保護区で見つかったプレート間(コラザクロウ、紀元前7世紀の後半、H 37センチ、アテネの国立考古学博物館と呼ばれる)オリンピアで見つかった胸の奥に、この期間に属していますならびにゼウスとアポロの出会いとして同定されているグループの場面など。 [16]グリフィンのヘッドは、拡散方法で発見された:東部原産の素晴らしい動物は馬に供される有機法律にギリシャの領土に提出されますおよび他のペット[17]セット間ギリシャ人の標本は、この正式な明快さと衝撃放置しているようだ。 [17]

東影響が刻まれた宝石の生産に感じられます。 象牙のシールの使用を拡大しているペロポネソスにいる間、島ミケーネは復活は、より丸みを帯びた形状や硬石のミケーネ旋盤加工と同じ技術につながる。 [18]ギリシャの島々と東でも、頻繁プレートであります金と銀は、ネックレスや他の宝石類に属する可能性が高い要素は、ケンタウロスのエンボスイメージまたはに関連した問題で飾らセロン 。 島で頻繁には、洗濯機および電気銀が細かく、中央ヘッドグリフィン、または他の比喩で働いていました。]テーマバックロードスやミロのイヤリングでグリフィン。 [19]

聖域のお店もの小さな彫刻の生産継続象牙を 、多くの場合、オブジェクトや家具のための装飾として使用されたその処理技術、一緒に東から輸入した材料のいずれかを。

アルカイック彫刻

この期間に生産がそれぞれ最も豊富 の複数形(「子」)と高麗(「女の子」)、人物、若者、男性と女性の、の、知的および物理的な開発の高さで、まだ退廃が触れていないということです。形状や体の動きを簡略化して低減され、像が動きを示すために、前脚(通常は左)と、多くの場合、またはほぼ等身大、(スタンディング)ダイエット、まだ硬いと聖職のポーズをとっています典型的で古風な笑顔 。 ヌードは、おそらく選手のカスタムに由来する裸競います。 彫像は、神社に神へのコミュニティのまたは個別の贈り物を配置することができる、彼らは神ご自身を表すことができ、捧げ、または美しく、完璧な人間だけの画像。 彼らは墓に入れることができ、あるが故人の画像である可能性があります。 その埋葬クーロスを持っている可能性があっても古い、我々は碑銘源持つ[20] 。

使用されたパロス島の大理石や地元の石、あるいはテラコッタ :製錬の技術青銅を 、実際には、まだそれは大きな彫像の実現を可能にしませんでした。 作品は、顔料の損失の後、今誰が白とは対照的に、あっても明るい色で、過半数に塗られ、それが美的に形成されたネオクラシカル 。

彫刻古風それは古代ギリシャの様々な分野に関連して、いくつかの電流を区別するのが通例であるドリス式 、「 屋根裏とイオン 。 最初の彫刻巨大な体、対称、要約、時にはスクワット、オンラインと振動luministicの増加焦点の資格をよりほっそりとしたエレガントな第二、最終的には前の2つの文体の研究をまとめたもので、第3、表現する自然主義周囲の空間との関係に銅像を置くために意図。

古風な彫刻の重要な側面は、係る建築装飾の開発であるペディメント 、 メトープとフリーズし 、それは宗教的なアーキテクチャの文脈でギリシャ文明の進捗状況と手をつないで行きます。 今の社会的、政治的な側面に接続生産、特に別の大きな分野は墓石のような象徴的図と救済または列で装飾スラブから作られたということであるスフィンクスや簡単な手のひら 。 時代の偉大な彫刻家の名前のいくつかは、ソースによって受け継がれてきたか、彼らの作品に基づいて彼らの署名を残しています。 イオニアとキクラデス諸島からサモとの名前来るキオスのを、とテオドロ、彫刻家や建築家で、伝統はロストワックス技法でギリシャのブロンズ像の導入を割り当てます。 ギリシャ、東アッティカの間図リンクはあるパロスのAristion彫刻家の屋根裏部屋は完全にあったが、 と。

期間重度

の終わりに向かって6世紀紀元前から広がるペロポネソス 古典期間が言ったのと予想しているスタイルを、それが船尾またはを定義されています。 それは、他のもののうち、顔が常に笑顔のように提起された応じた古風な伝統の最後の克服をカバー。 人間の頭の解剖学的構造の知識の進歩のおかげで、丸顔基本的に球形になり、したがって、目と口が右割合やプレースメントでした。 新しい技術的な可能性は、この意味で、近づいて、顔の表情要求をロールプレイングから可能になった、より自然な表現に彫刻。 筋肉量は、拡散や筋肉のパワー感を増大させる たボディ構造、肩や胴体に調和分布しています。 アーチは、アーク上腹部を指摘され、彼は彼の膝を薄くし、図全体を。

この時代の彫刻のために最も広く使用される材料があった青銅マスターズ の技術の適切な実験的な態度の使用を含んで、。数値は、最初にモデル化された粘土 、その後の層でコーティングした、仕事の自由な作成と操作を可能にする、 ワックス ; 後者は再びだった金型を作成するために、粘土で覆われていた(で技術を鋳造溶融銅メダルを注ぐロストワックス )。

時代の大きなブロンズ像は、材料の再利用に深刻な破壊を生き延びています。l ‘ デルファイの御者 、デボンシャー公爵に属しキプロスから来た頭、として知らアポロチャッツワース 、 で海で見つかった、 岬 有名なのと、少なくとも一つのブロンズ像 。常にブロンズではなく、唯一のローマ時代の大理石のコピーを使用して既知の作品だったマイロンするエル’ アテナとマルシュアス [22] 、これらの年の間に取得された図形の動きに関連した実験や研究を例示します、 「時間的に凍結した運動の一つの態様は:も参照のグループ 、 エギナのペディメントとオリンピアのゼウス神殿の西ペディメントを 。

古典期後期古典

世紀中期の紀元前に出現古典時代の彫刻の像は彫刻の装飾が例示されるパルテノン神殿とその彫刻Polykleitos 。 体の解剖学や彫刻家は、今、私たちは前の期に比べて、より自然で多様なポーズで神々や英雄を描くために、名前でほとんどの人が知っていることを可能にする技術的な専門知識の知識。 技術的熟練はの彫刻です五世紀によって新たな課題に開く、次の世紀に継続されます古典的な美学の最高峰、 リュシッポス 。

条約に固定されたコピーのみを、所有し、また、身体(の様々な部分の調和のとれたプロポーションのために、カノン(有料)を題した、ルールを失っ、 ディアドゥメノス )。

記念碑的なカルトの彫像との建設始まる金と象牙で作られた 、すなわちでコーティングされ、 金や象牙のように、 オリンピアのゼウス像 (の1 世界の七不思議 」で) 同じ名前の寺院やのアテナパルテノスでパルテノン神殿 、両方によって作らFidia 。 の有名な彫刻ではパルテノン神殿 、アーティストが本物の叙事詩を作成し、すべての当事者は、前例のない明確な主題リンクと継続性プラスチックを持っています。イオンのフリーズで行列の現代人類、メトープで人類英雄神話、ゲーブルズの神。 クライマックスは、(「非常に自然製の厚さと豊かなドレープでドレス東ペディメントに描かれた彼らの神々に達するウェットカーテン 」)。

フィディアスの後、学生との従業員が含まれている期間、など、さまざまな環境で教育を受けた他のアーティスト以外にもカリマコスとメンデによって例示の移行期間があるがとして数値 エルダーそれは一般の父とみなされていることを、非常に重要なの彫刻家プラクシテレス、およびティモシー。

後期古典期 の間に、敗戦続き権力と富の損失ペロポネソス戦争は、重要な文化と芸術の中心地であり続けるためにアテネで停止しませんでした。この時期の芸術家は、しかし、彼らは経済成長の小さな町の当局による、または裕福な市民によって呼び出さ素晴らしい旅行者、となります。彫刻家は、常により多くの絶賛されている が四世紀プラクシテレスと彼の側では、配置されている 好きなアーティストアレキサンダー大王最終ブレークにつながった、比例システムと図形と空間との関係で重要なイノベーションの提唱者、古典的な技術とし、ヘレニズム美術行わ新たな問題を郵送。体のストレッチと洗練された位置の自然の比率でLisippoが強調されます。期間の他の重要な彫刻家であったのために働いた、偉大な彫刻家とブロンズ労働者フェリペ2世とマケドニア王朝。4世紀紀元前の最も重要な記念碑は間違いなくあったハリカルナッソスの霊廟が、ギリシャの彫刻の発展に等しく重要いたエピダウロスアスクレピオスの神殿とアテナアリアの寺院でテゲアを。

ヘレニズム時代

ベルヴェデーレトルソー。ローマ·バチカンの博物館 で。

ヘレニズム時代の彫刻は、正式な主題やコンテンツ決定的リニューアルとの最も創造的で前期とは異なります。それはもはや寺社や公共のお祝いのために確保するだけでなく、民間部門に入るし、豊かな一流の装飾として、例えばデロスの民家で発見を参照してくださいません。当社は、新たな科目を検索し、描画や日常生活の現実的な描写(古い酔っては、ガチョウで遊ん子)至上の技術スキルと妙技で処理されたが、カーテンを作りました。

紀元前3世紀の 年代から適切ヘレニズム日付彫刻、の死から数十年前、ながらアレキサンダー大王が信者と プラクシテレスとリュシッポスの学校に支配されている。[23]特に撮影中リュシッポスの学生新しいアートセンターの彫刻の最も革新的な側面の発展にとって非常に重要であったマスターの新しい美的を転送。この地域で最も重要な人物の中にあるとリンドスのカレスは。:半ば紀元前3世紀からの第二の中間に中間ヘレニズムの位相が、文化の発展の新たな中心の出現見るロードス、アレクサンドリアとペルガモンを。特に後者は政治的プロパガンダによって特徴付けられる アーティストの作品を通じて実装、哲学者や科学者は、裁判所の羊皮紙に引き寄せ。時代の最も有名な名前の中には ペルガモンとするアテネ。紀元前1世紀の半ばからアウグストゥスの時に最後のヘレニズム時代、とも呼ばれる古典の出現、見 クラシック時代の作品や前段ヘレニズムの復活で、およびneoellenismoを、時には再加工、 、主にバイヤーのローマからの需要の結果として。最もよく知られているの一つはclassicistsです。

成果文体特徴は、有名なような複雑なと名人芸の組成物、苦しめポーズまで達成技能が活用されるラクーンや有名なベルヴェデーレのトルソのバチカン美術館を。賞賛と研究ルネサンスにされ、これらの作品は、最後のヘレニズム期のものは、ミケランジェロを刺激します。でも表情はあなたが情熱的で困っ作り、あなたはヘレニズムの支配者、最初の肖像画のものとがあります。

注

- ^ ビアンキバンディネリ、。

- ^ 参照記念碑的な彫刻の荒加工や輸送に関連する問題の例について。バーナードアシュモール、「オリンピアのゼウス神殿。プロジェクトとその「古典的なギリシャの建築家や彫刻家、ニューヨーク、ニューヨーク大学、。

- ^ リヒター年に、ここかしこに。

- ^ リヒター頁。。

- ^ ニューヨーク、メトロポリタン美術館、ブロンズ男とケンタウロス、17.190.2072を。年2月25日に取り出されます。

- 年ビアンキバンディネリ、カード

- 年ビアンキバンディネリ、タブを

- 頁。

- ^ リヒター頁。

- 年ビアンキバンディネリ、タブを。

- 年ビアンキバンディネリ、タブを。

- ^ リヒター頁。

- ^ リヒター頁。

- 年ビアンキバンディネリ、タブ

- 年ビアンキバンディネリ、カード。

- 年ビアンキバンディネリ、タブ

- 年ビアンキバンディネリ、タブを。

- ^ リヒター頁。

- ^ リヒター頁。

- ^ ホーマン-頁。

- ^ ビアンキバンディネリ、

- ^ デベッキ- 頁。

- ^ ジュリアーノ、

参考文献

- エルンストホーマン- 古代ギリシャ、ミラノ、ベーシックブック、

- ジャンローランド·マーティン。フランソワ·ヴィラール、ギリシャ古風な から )、ミラノ、リッツォーリ、年 存在しません

- ギゼラ リヒター、ギリシャの芸術、トリノ、エイナウディ、

- フックス、ギリシャの彫刻の歴史、ミラノ、からマーク·ジェフリーHurwit、初期のギリシャの芸術と文化:紀元前 年に、ロンドン、コーネル大学出版、年、

- ビアンキバンディネリ、エンリコパリベーニ、古典古代の芸術。ギリシャ、トリノ、図書館、

- アントニオ·ジュリアーノ、ギリシア美術:年齢古典的なヘレニズム時代から、ミラノ、試金、

- カルロバーテリ、アントネッラ。アンドレア·ガッティ、美術史:カロリング朝にその起源から、ミラノ、学校ブルーノモンダドーリ、

- マイケル·ガガーリン、エレイン古代ギリシャやローマのオックスフォード百科事典、オックスフォード、オックスフォード大学出版、年、

他のプロジェクト

その他のプロジェクト

外部リンク

Category Archives: パワーと情念

Giacobbe Giusti, KRAFT UND PATHOS: BRONZEN DER HELLENISTISCHEN WELT

Giacobbe Giusti, KRAFT UND PATHOS:BRONZEN DER HELLENISTISCHEN WELT

14 März 2015

Die Ausstellung im Palazzo Strozzi, erzählt die künstlerischen Entwicklungen der hellenistischen Zeit (IV-I Jahrhundert vor Christus), durch außergewöhnliche Bronzestatuen. Zu sehen sind einige der größten Meisterwerke der Antike von den wichtigsten archäologischen Museen italienischen und internationalen.

Monumentale Statuen von Göttern, Sportler und Führungskräfte sind mit Porträts historischer Persönlichkeiten gepaart, den Weg, der den Besucher in der Analyse der Produktionstechniken führen wird, Gießen und Veredelung aus Bronze und entdecken Sie die Geschichten von den Ergebnissen dieser Meisterwerke.

In sieben thematische Abschnitte unterteilt, öffnet sich die Ausstellung mit der großen Statue von Arringatore, ein Teil der Sammlung von Cosimo I. de ‘Medici und der Sockel der Statue von Lysippos, im Jahre 1901 in Korinth gefunden.

Setzt sich mit der Übersicht über die Portraits der Macht, die die Bildnisse der einflussreichsten Menschen der Zeit bietet. Ausgestellt außergewöhnliche Beispiele, wie die Figur von Alexander dem Großen zu Pferde, der Kopf-Porträt von Arsinoe III Philopator, die eines Diadochus und die einer wahrscheinlichen General.

Der vierte Abschnitt mit dem Titel “Realismus und Ausdruck” analysiert die einzelnen Porträts, die Verwendung von Inlays und Farbe, um ein natürliches Aussehen zu erhalten und betont das Pathos und andere Formen der Charakterisierung, wie wir in dem Bild des jungen Aristokraten und viele andere zu sehen Heads-Porträt männlich.

Der fünfte Abschnitt “Replicas und Mimesis”, wollen die Idee von der Kapazität der Bronze geben mehrere “Original” zu schaffen, hat in der Tat, Reproduktionen von hellenistischen Werken in den Folgeperioden, die Nachahmung der Bronze in der dunklen Stein und andere Aufbewahrungs Bronzen auf See von den in der Erde gefunden.

Der sechste Abschnitt “Divinity”, mit Werken von außergewöhnlicher Schönheit, einschließlich der Minerva Arezzo, das Medaillon mit der Büste der Athena und dem Kopf der Aphrodite.

Schließlich ist der siebte Abschnitt “Stile der Vergangenheit”, will ein neues Interesse an den archaischen und klassischen Modellen zusammen mit dem Stilmix späthellenistischen entdecken. Zu den wichtigsten Beispiele für die so genannte Idolino Pesaro und dem Apollo der Louvre in Paris.

PALAZZO STROZZI

-Palazzo Strozzi, Florence, Italy

March 14 – June 21, 2015

http://www.palazzostrozzi.org

-J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA

July 28 – November 1, 2015

http://www.getty.edu

-National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

December 6, 2015 – March 20, 2016

http://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/exhibitions/2015/power-and-pathos.html

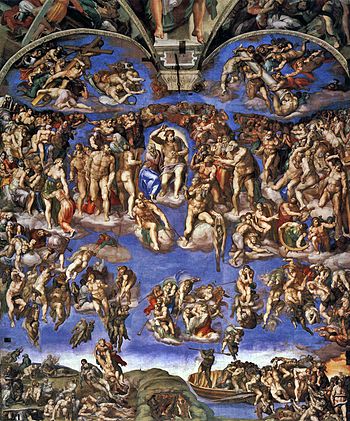

Giacobbe Giusti, The Last Judgment by Michelangelo

Giacobbe Giusti, The Last Judgment by Michelangelo

|

|

| Artist | Michelangelo |

|---|---|

| Year | 1536–1541 |

| Type | Fresco |

| Dimensions | 1370 cm × 1200 cm (539.3 in × 472.4 in) |

| Location | Sistine Chapel, Vatican City |

The Last Judgment, or The Last Judgement (Italian: Il Giudizio Universale),[1] is a fresco by the Italian Renaissance master Michelangelo executed on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City. It is a depiction of the Second Coming of Christ and the final and eternal judgment by God of all humanity. The souls of humans rise and descend to their fates, as judged by Christ surrounded by prominent saints including Saints Catherine of Alexandria, Peter, Lawrence, Bartholomew, Paul, Sebastian, John the Baptist, and others.

The work took four years to complete and was done between 1536 and 1541 (preparation of the altar wall began in 1535.) Michelangelo began working on it twenty five years after having finished the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

An older and more thoughtful Michelangelo originally accepted the commission for this important painting from Pope Clement VII.[2] The original subject of the mural was the resurrection, but with the Pope’s death, his successor, Pope Paul III, felt the Last Judgment was a more fitting subject for 1530s Rome and the judgmental impulses of the Counter-Reformation. While traditional medieval last judgments showed figures dressed according to their social positions, Michelangelo created a new standard. His groundbreaking concept of the event shows figures equalized in their nudity, stripped bare of rank. The artist portrayed the separation of the blessed and the damned by showing the saved ascending on the left and the damned descending on the right. The fresco is more monochromatic than the ceiling frescoes and is dominated by the tones of flesh and sky. The cleaning and restoration of the fresco, however, revealed a greater chromatic range than previously apparent. Orange, green, yellow, and blue are scattered throughout, animating and unifying the complex scene.

Reception and expurgation

1549 copy of the still unretouched mural by Marcello Venusti (Museo di Capodimonte, Naples).

The Last Judgment was an object of a heavy dispute between critics within the Catholic Counter-Reformation and those who appreciated the genius of the artist and the Mannerist style of the painting. Michelangelo was accused of being insensitive to proper decorum, in respect of nudity and other aspects of the work, and of flaunting personal style over appropriate depictions of content. He was considered to have gone much too far in his beardless and muscle-bound figure of Christ, which very clearly adapted classical sculptures of Apollo, and this path was rarely followed by other artists.

A few years after the fresco was completed, the decrees of the Council of Trent urged a tightening-up of church control of “unusual” sacred images. In response to certain accusers, when the Pope’s own Master of Ceremonies Biagio da Cesena said of the painting “it was mostly disgraceful that in so sacred a place there should have been depicted all those nude figures, exposing themselves so shamefully,” and that it was no work for a papal chapel but rather “for the public baths and taverns,” Michelangelo worked Cesena’s face into the scene as Minos, judge of the underworld (far bottom-right corner of the painting) with Donkey ears (i.e. indicating foolishness), while his nudity is covered by a coiled snake. It is said that when Cesena complained to the Pope, the pontiff joked that his jurisdiction did not extend to hell, so the portrait would have to remain.[3]

The genitalia in the fresco, referred to as ‘objectionable,’ were painted over with drapery after Michelangelo died in 1564 by the Mannerist artist Daniele da Volterra, when the Council of Trent condemned nudity in religious art.[1] The Council’s decree in part reads:

Every superstition shall be removed … all lasciviousness be avoided; in such wise that figures shall not be painted or adorned with a beauty exciting to lust… there be nothing seen that is disorderly, or that is unbecomingly or confusedly arranged, nothing that is profane, nothing indecorous, seeing that holiness becometh the house of God. And that these things may be the more faithfully observed, the holy Synod ordains, that no one be allowed to place, or cause to be placed, any unusual image, in any place, or church, howsoever exempted, except that image have been approved of by the bishop.[4]

Restoration

The fresco was restored along with the Sistine vault between 1980 and 1994 under the supervision of curator of the Vatican Museums Fabrizio Mancinelli. The illustration reflects the restoration. During the course of the restoration about half of the censorship of the “Fig-Leaf Campaign” was removed. Numerous pieces of buried details, caught under the smoke and grime of scores of years were revealed after the restoration. It was discovered that the fresco of Biagio de Cesena as Minos with donkey ears was being bitten in the genitalia by a coiled snake. Another discovery is of the figure condemned to Hell directly below and to the right of St. Bartholomew with flayed skin. It was, for centuries, considered to be male until removal of the “fig leaf” showed that it was female.

Detail

|

『最後の審判』(さいごのしんぱん、イタリア語 Giudizio Universale)は、ルネサンス期の芸術家ミケランジェロの代表作で、バチカン宮殿のシスティーナ礼拝堂の祭壇に描かれたフレスコ画である。1541年に完成した。

これより先、ミケランジェロはローマ教皇ユリウス2世よりシスティーナ礼拝堂の天井画を描くよう命じられ、1508年から1512年にかけて『創世記』をテーマにした作品を完成させている。それから20数年経ち、教皇クレメンス7世に祭壇画の制作を命じられ、後継のパウルス3世の治世である1535年から約5年の歳月をかけて1541年に『最後の審判』が完成した。天井画と祭壇画の間には、ローマ略奪という大事件があり、今日、美術史上でも盛期ルネサンスからマニエリスムの時代への転換期とされている。

ミケランジェロが『最後の審判』を描くより前、祭壇画としてペルジーノの『聖母被昇天』が描かれており、ミケランジェロは当初ペルジーノの画を残すプランを提案していた。しかしこの案はクレメンス7世により却下され、祭壇の壁面の漆喰を完全に剥がされてペルジーノの画は完全に失われた(スケッチのみが現存する)。 ペルジーノが描いた『聖母被昇天』には、画の発注主であるシクストゥス4世の姿が描かれていたことが判っており、パッツィ家の陰謀により実父を殺されたクレメンス7世による、事件の黒幕とされるシクストゥス4世への復讐であった可能性が指摘されている。

『最後の審判』には400名以上の人物が描かれている。中央では再臨したイエス・キリストが死者に裁きを下しており、向かって左側には天国へと昇天していく人々が、右側には地獄へと堕ちていく人々が描写されている。右下の水面に浮かんだ舟の上で、亡者に向かって櫂を振りかざしているのは冥府の渡し守カロンであり、この舟に乗せられた死者は、アケローン川を渡って地獄の各階層へと振り分けられていくという。ミケランジェロはこの地獄風景を描くのに、ダンテの『神曲』地獄篇のイメージを借りた。

群像に裸体が多く、儀典長からこの点を非難され、「着衣をさせよ」という勧告が出されたこともある。ミケランジェロはこれを怨んで、地獄に自分の芸術を理解しなかった儀典長を配したというエピソードもある。さらにこの件に対して儀典長がパウルス3世に抗議したところ、「煉獄はともかく、地獄では私は何の権限も無い」と冗談交じりに受け流されたという。また、キリストの右下には自身の生皮を持つバルトロマイが描かれているが、この生皮はミケランジェロの自画像とされる。 また画面左下方に、ミケランジェロが青年時代に説教を聴いたとされるサヴォナローラらしき人物も描かれている。

『最後の審判』などの壁画・天井画は、長年のすすで汚れていたが、日本テレビの支援により1981年から1994年までに修復作業が行われた。壁画・天井画は洗浄され製作当時の鮮やかな色彩が蘇った。ミケランジェロの死後、裸体を隠すために幾つかの衣装が書き込まれていたが、これは一部を除いて元の姿に復元された。

徳島県鳴門市の大塚国際美術館には実物大のレプリカが展示されている。 京都府京都市の京都府立陶板名画の庭にも、陶器製のほぼ原寸大のレプリカが展示されている。

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Last_Judgment_(Michelangelo)

Giacobbe Giusti, MONTE FALTERONA, ‘IL LAGO DEGLI IDOLI’

Giacobbe Giusti, MONTE FALTERONA, Il lago degli idoli”

votive figure; Etruscan; 425BC-400BC; Chiusi; Falterona, Mount , British museum

votive figure; Etruscan; 400BC-350BC; Italy; Falterona, Mount , British museum

figure-fitting; Etruscan; 420BC-400BC; Italy; Falterona, Mount , British museum

figure; Etruscan; Italy; Falterona, Mount , British museim

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx?place=34986&plaA=34986-3-1

Kouros

bronzo – h. 18 cm

Etruria, prov. Falterona – secondo quarto del V secolo a.C.

Parigi, Musée du Louvre

Parigi, Musée du Louvre

stipe materiale: bronzo

dimensioni: cm 14

votiva del Falterona: offerente femminile

I bronzi degli Etruschi

Istituto Geografico De Agostini

Milano, 1985

FALTERONA, THE “LAKE OF IDOLS”.

“Nullus enim fons not sacer”

(Servius, ad Aen, 7, 84)

One day (in May 1838) In the woods

Monte Falterona a shepherdess saw emerge

on the shores of Lake of Ciliegeta (approximately

1,400 meters above sea level) the first piece of a

great archaeological discovery.

The shepherdess perhaps had not recognized

the bronze statue, which his hands had

extracted from the ground, Hercle (the Heracles – Hercules

classical mythology) but he understood that

it was a precious object.

Following this discovery it was organized in Stia

a society of “amateurs” local order

to organize further research.

The excavations led to the drying up

of the water and the discovery of

one of the richest in the world votive

Etruscan, he did take to the site

name “Lake of Idols”

(FORTUNA GIOVANNONI, 11 et seq .; DUCCI 2003

11 et seq.).

“In only one day on the banks it was

well found 335 bronzes and public

after other material is added, so as to

forming in a short time the exceptional

discovery of more than 600 pieces, including statues

Human complete, small heads, parts

anatomical (busts, eyes, arms, breasts,

legs, feet), animal figures, different

fibulas, some 1,000 pieces of aes rude (pieces

bronze irregular used as rudimentary

currency), a few pieces of aes signatum

(Pieces of cast bronze to form generally

ovoid with rough signs indicating the value) and

of aes grave (the very first coin form

round with figures that identify value

and origin) “, a coin, probably

Roman, portrayed with Janus and a temple,

“Over 2,000 arrowheads, several

fragments of iron weapons and pottery ”

(DUCCI 2003, 11).

These findings are not the flower

cap of some museum Tuscan.

Unfortunately, after being unnecessarily

Granducali offered Authority, the “members

researchers “got permission to sell

to third parties. The rich collection was sold in

block and cheaply. It was edited

an exhibition in December 1842 at

the German Archaeological Institute in Rome

and this is the last news we have of the

stipe complete.

At the British Museum the seven bronzes

from the Lake of Idols occupy a

place of honor; others are in the Louvre;

one in Baltimore and one bronze sheet is to

National Library in Paris (FORTUNA

GIOVANNONI, 16-18; DUCCI 2003, 13-15). The rest

dispersed who knows where, except, perhaps, those

which should be in stores

Hermitage in St Petersburg. The

recognition of the origin of some

finds it has been possible thanks to the descriptions

and drawings that had published the Micali

(1844).

The revival of interest in the lake

Idols coincided with the emergence of

so-called “archeology of the cult” in which

recent years is attracting attention

scholars, from prehistoric to pre-classic.

“The custom, probably

background ritual or votive, to throw in the waters

metallic objects of prestige or a redemption

close to them is a phenomenon that,

at least as regards Europe, it seems

involve all prehistoric societies and

protostoriche. Recent studies, in fact, reveal

that this particular rite, linked to water

(Rivers, streams, lakes, swamps, bogs) has

lasted quite long, that age

Copper (3,400 BC) comes up to the second

Iron Age (the second half of the first millennium

BC) with a peak in the late Bronze Age

(XIII – the first half of the twelfth century

A.C..). More recent surveys show,

then, that the weapons (swords, daggers, tips

spear, ax) are almost exclusive during

the Bronze Age, while towards the end of

this period and in the Iron will

or make an appearance alongside other

objects, such as pins, knives, razors, helmets,

pruning hooks, rings, bronze and pottery. ”

“The memory of this ancient

rite remains, however, with the end

of society classic. To evoke the ties

with these practices and prehistoric

protostoriche are just two examples:

Breton myth of Excalibur, the magic sword

King Arthur (now at death), which must

be thrown in the water and returned to the

Lady of the Lake; or, coming to our

time, the coins thrown into the fountain

Trevi in Rome, ‘… if late and playful’ (for

In the words of the philologist Walter Burkert)

‘Sacrifice for immersion …’ “(Swans

Sun, 47-48).

In the wake of the discovery of three more

bronzes very deteriorated, in 1972 it was decided

by the then Superintendent of Antiquities

Etruria a limited test excavation under the

direction of Francesco Nicosia (Profile of a

Valley, 52). But – as we learn from your site

the City of Stia – “the gods disturbed

They expressed their impatience with a

persistent rain, despite being full

August. ”

The recent project “Lake of Idols”

He foresaw the systematic excavation with

recovery of the material omitted from the excavations

nineteenth century, the study of the site, with analysis

pollen, stratigraphic and geomorphological:

work completed in September 2006. The results,

presented at a conference held in the Poppi

the end of the same month, have shown

the Lake of Idols appears to be the stipe

Votive that returned the highest number of

findings. E ‘provided for the restoration of the mirror

water of the lake, “to offer again

that image of the visitor magical place,

that the ancient Etruscans reached with

devotion and effort “(DUCCI 2003, 18, DUCCI

2004, 6-8). The results of the excavation

2003 conducted by Luca Fedeli were

presented in the exhibition “Sanctuaries in the Etruscans

Casentino “of 2004.

The pond, still in some papers

eighteenth century seems to indicate which source

Arno, although today is referred to as

“Capo d’Arno” the source which is about 500

meters from the site; “Some scholars was

It speculated that in ancient was also considered

the source of the Tiber, since the two rivers

still united through the dense network of canals

formed the Valdichiana “(DUCCI 2003, 16;

FORTUNA GIOVANNONI, 45-48: “Falterona, and Arno

Tiber “).

The sacredness of the Falterona not drift

only from the sources but, despite the

if not excessive height of the top

compared with those mountain (1,654 meters),

from the mountain of a dominant

wide area of Tuscany and neighboring regions.

Visible from the Florentine plain as

Arezzo and from which you can gaze on

a large part of the Apennine Mountains and valleys

adjacent. Near he was to pass a

Apennine road linking Etruria

internal and Etruria Padana as bronzes

found were attributed to factories

Etruscan Po Valley area, as well as Orvieto,

Umbrian and Greek (FORTUNA GIOVANNONI, 31-

36, DUCCI 2003, 14-15). Still at the end of

VII sec. B.C. Casentino was the

offshoot’s northernmost territory

Etruscan, in direct contact with two of

people who lived long ago Italy

Central: the Ligurians in the north and the east of Umbria

(DUCCI 2003 4 THE BRIDGE 1999 Profile of a

valley).

“As for the name of the mountain in

Specifically, Devoto (in ‘Studies Etruscans’, XIII,

1939, p. 311 et seq.) It considers derived from a

plural Etruscan FALTER or faltar, (…)

adds that FALTER derives his

Once a root PAL-FAL, which took

expansions in -T (FALT-, in fact), in -AT

(PALAT-, from which ‘palatium’, the ancient name

Palatino) or -AD (FALAD-, from which

‘Falado’, adaptation of a voice Etruscan

meant ‘sky’ second Festus v. M.

Pallottino, ‘Witness the tongue Etruscae’,

1968 n. 831). Also according to the Devoto, the

PAL-root / Falzone had to indicate ‘a

round shape or a shape object

unspecified which has the function of cover ‘, from

where the more specific meaning of ‘time’,

‘Dome’. The Falterona would be that ‘a

set of domes’. ”

“It ‘should be noted, however, that the current form has a

Termination (-NA) of Etruscan own (not

attested in those that would phases

according to previous language

reconstruction of Devoto) can not be excluded

namely, that the etymology today is an adaptation

min a form with that Etruscan

termination. And ‘perhaps too simplistic

think of a compound name forever from

root Falzone, ‘dome’, ‘time (blue)’ and

Truna (etymology Etruscan according Hesychius

He corresponded to greek ARKE ‘=’ power ‘,

‘Principle’) that would mean Falterona

‘Principle of heaven’? “(Fortuna in FORTUNA

GIOVANNONI, 37 n. 2).

So also in the name of the Falterona

She recalls its ties with the sacred.

“The sacredness is

their places

dark and shadowy,

in the twilight

thought it collects

and tempers

unfold according

facets of

heart.

Evocations

need

places elected and

forest, the kingdom of

darkness and silence,

It is a perfect place for

excellence.

And if the desert,

hermitage of

holy, it is the place of the truth because there

shadows are, in equal measure the wood is

place the enigma of life, where the shadows

a teeming multiplicity transform

landscape in a constant metamorphosis and

where the soul escaped the constraints of time and

Space unfolds according to natural rhythms

in a kind of empathy with nature, in violation

codes of communication usual. ”

“The forest has since ancient place

sacred and initiation. In the Celtic tradition

Druids celebrate their rites in the forest

where some trees, considered sacred, defined

spaces reserved for ceremonies. Even among

Germans the oldest sanctuaries were

probably natural woodland. In

symbolism of the forest come together two

elements: on one hand the opening towards the

sky, home of the divine, the other clear,

definition of a protected and secret,

where the rites were held. The sacredness extended

then also the cult of the trees (…). ”

“The forest is also the place where it was

kept the primordial knowledge and place

the initiation tests “(Maresca, 7).

The sacred grove is a lucus, but with lucus

etymologically he was intended to “clear”.

As also noted on the border between Dumézil

the two meanings is not absolute and

probably the passage of the meanings is

It took place in a stadium of the ancient language

(Dumézil 1989, 46). Perhaps it is good to remember that

concepts sacrum, sanctum and religiosum

They are not interchangeable. “The same can res

be ‘sacred’ as consecrated to the gods,

‘Holy’ as subject to sanction of law,

‘Religious’ as to violate it are offended

the gods “(BRIDGE 2003).

The sacred groves, although recognized

property of a god given (or not), were

under certain conditions accessible to action

profane (economic exploitation). Before

cut a part of the forest, according to the

ancient prayers handed down by Cato, the

farmer sacrificed a porco1 turning to

1 It is worth mentioning that “a requirement for the

validity of the offer and of the ritual that the

victim manifested in some way its

consent. For this reason the animal could not

be conducted in force at the altar, as this would

It represented a very bad omen for the success of

sacrifice “(SINI 2001, 200).

god or goddess of the place “anyone” 2. And for

the gods of the woods you get to talk to

“Fauns” and “sylvan” (Etruscan Selvans) to

plural forms of the ancient Latin Italic

Lord of the Animals (BRIDGE 1998 162-

163).

“Nullus lucus sine source, nullus fons

not sacer “reminds us Servius (ad Aen, 7, 84)

a natural association and sacredness

of one automatically switches to the other. But

what will be the divinity of the Lake of Idols? The

Roman calendar celebrates October 13

Fontinalia, devoted to natural sources in

which were thrown crowns and crowned the

wells, dedicated to Fons (Source) son of Janus

and Juturna (Juturna, Diuturna) (DEL PONTE

1998, 66, Dumézil 1977 339-340, Dumézil 1989

25-44, BEST 1981 14 SABBATUCCI, 29-30 and

328-329 [Which highlights, too, the link between

Fontinalia, festivity spring water, and meditrinalia,

October 11, one of the wine festivals, in their aspects

“Medicated”]). As part of Janus (I

I like to recall that the two-faced god is only

in the pantheon Latin Ianus, and in that

Etruscan Culsans), the “good owner” of the

Carmen Saliare, include sources, not

only as the father of the god-Fons and river

Tiber, for having saved Rome from

Sabine assailants doing gush before

them a hot spring them

frightened and routed them, but also because

patron of beginnings (BRIDGE 1992 and 1998

Dumézil 1977 D’ANNA).

Not taking into account these

characteristics, the currency found in Giano

pond might seem the result of

some random fact but also the spread

of hydronyms derived from the name of DIO3

It helps to prove otherwise.

Especially near the name “Mount

2 Cato, De agr. 139: Locum conlucare Roman Opinions more

sic oportet: pig piacolo facito, verba sic conceived:

“It deus, you goddess es quorum illud sacrum est, ut tibi ius

east hog piacolo illiusce sacred coercendi ergo

harumque rerum ergo, sive ego sive quis iussu meo

fecerit, uti id recte factum siet, eius rei te hoc ergo

pig piacolo immolating bonas preces precor uti sies

volens Propitius mihi, domo familiaeque meae

liberisque meis, harumce rerum ego Macte hoc porcum

piacolo immolating esto “(SINI in 1991, 114, n. 97).

3 Fatucchi A., Janus on the trail of the cult of the Sun in

Arezzo area, Arezzo S.A., cited in FORTUNA

GIOVANNONI 1989, 40 n. 5.

Gianni “vulgar corruption of the Latin” Mons

Iani “(Apparently, in fact, still in the nineteenth century cha

the location was called Monte di Giano,

although the popular mispronunciation beginning

to indicate its present name) making

conceivable “that even the patronage of

god involve the entire Monte and

considering the name of the township

casentinese the same way as the Latin oronimo

Falterona “(Profile of a valley, 105 FORTUNA

GIOVANNONI, 39-40 and relevant bibliography).

“Macrobius (1, 11) evoked, among

insights of the ancient world of investigators

archaic, one that brightly in -anscorgeva

the ‘heaven’ “recalls Semerano

referring to said component within the

names Culsans and Ianus (123). A Further

relationship between Janus and Falterona?

Excluding the currency with the two-faced god, the only

This deity is Hercules (the famous

bronze now in the British Museum and in another

now lost but played between designs

Micali, probably produced umbra)

suggesting that it was the tutelary deity

the sanctuary.

The cult of Hercules was widespread

in ancient Italy, he traveled back with

the oxen of Geryon or in search of

Garden of the Hesperides, among the various peoples of the

Saturnia Tellus (BRIDGE 2003

MASTROCINQUE 1994). “Elected deity

patron of spring water, and worshiped

as patron saint of travelers, shepherds and

merchants: the presence of images of

animals, cattle, sheep and poultry, reproduced in

miniaturization in place of the real,

suggests the protection required to

god from pastors who probably

with their flocks migrated along the pass

Apennine restaurant nearby. The remains of

numerous weapons, together with the representation

warriors and armed youths, recall

instead the request for protection by

military, which in large numbers must be

passed near the lake. Lastly, the presence

anatomical parts of the human body seems

addressing the request for a pardon or

votive offering to the god of a body part

where it could have happened a healing “(

DUCCI 2003, 16).

But Hercules was also the ancestor

“Common” of the Etruscans and Romans.

“Son of Hercules and Omphale was

Tirreno (Dion.Hal.I.28; Paus.II.21.3; Hygin., Fab.

274), or the king Tuscus (Fest., P.487 L .;

Paul.Fest., P. 486 L), founders of the Tirreni ”

(MASTROCINQUE 1993, 23). While according to

some traditions Ercole with the daughter of Fauno

begot Latino (MASTROCINQUE 1993 and 23-41

relevant bibliography). As he wrote

the scholar Giovanni Nanni Annio in bloom

humanism, Hercules would divinity

protect Arno (FORTUNA GIOVANNONI

1989, 27-28, n. 17).

We hope to see again in the coming years

in Casentino, during a show in

programming, the “Idols” Falterona

dispersed throughout the world, at least those

identified, along with the latest discoveries.

Mario Enzo Migliori

http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monte_Falterona

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monte_Falterona

http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mont_Falterona

Click to access 2007-MarioEnzoMigliori-FalteronaLagoDegliIdoli.pdf

Giacobbe Giusti, PUISSANCE ET PATHOS. Bronzes du Monde Hellénistique

Giacobbe Giusti, PUISSANCE ET PATHOS. Bronzes du Monde Hellénistique

La beauté à l’époque hellénistique bronzes exposés au Palazzo Strozzi

En collaboration avec J. Paul Getty Museum de Los Angeles di, la National Gallery of Art de Washington et de l’Archaeological Survey of Toscane, coup d’envoi de l’exposition «Pouvoir et pathos. Bronzes du monde hellénistique »dans le prestigieux Palazzo Strozzi.

Les animateurs, jusqu’au 21 Juin, Palazzo Strozzi à Florence, une extraordinaire série de sculptures à partir du quatrième siècle avant JC. au premier siècle D.C..

Pour la première fois réunis à Florence sur les 50 chefs-d’œuvre en bronze de la période hellénistique, IV-I siècle avant JC, qualité très expressive, faite avec des techniques raffinées dans un langage artistique très élaborée, y compris Apoxyomenos Vienne bronze et la version en marbre Offices utilisé pour sa restauration; i due Apollo-Kouroi, archaïsant au Louvre et à Pompéi.

Jusqu’à présent, aucun des couples ne avait jamais été exposé un à côté de l’autre.

Le Apoxyomenos est l’athlète qui nettoie la sueur à la fin d’une course, avec un métal incurvée outil spécial, ce strigile.

Les sculpteurs hellénistiques qui le premier a poussé à la limite les effets dramatiques de les rideaux étaient balançant, les cheveux en désordre, grimaces dents serrées; était entre leurs mains que les formes extérieures de la sculpture sont devenus tout aussi expressive de triomphe et de tragédie intérieure; et ce est dans leurs images de taille que nous voyons pour la première fois une représentation de tous les individus crédibles et événements réels, ils étaient des scènes de la vie quotidienne ou le combat entre Achille et chevaux de Troie.

La représentation artistique de la figure humaine est centrale dans la plupart des cultures anciennes, mais la Grèce est l’endroit où il avait plus d’importance et d’influence sur l’histoire ultérieure de l’art.

L’art sculptural était destiné à embellir les rues et les espaces publics, où commémorant gens et les événements, et le sanctuaire, où ils ont été utilisés comme des “votes”, o le case, où il a servi comme éléments décoratifs, ou dans les cimetières, où les symboles funéraires représentés.

Alla fine dell’età classica gli scultori greci avevano raggiunto un’abilità straordinaria, sans précédent dans le monde de l’art, imitant le corps de disposition et la forme plastique.

Le bronze, pour sa qualité, a toujours été considéré comme un métal noble et les artistes du monde antique étaient les maîtres dans le processus de fabrication du complexe métallique.

L’exposition est divisée en sept sections thématiques, ouverture avec la grande statue de la soi-disant Arringatore, ce était déjà partie de la collection de Cosme Ier de Médicis, pour indiquer combien d’intérêt produit les œuvres hellénistiques déjà à la Renaissance; poi prosegue con una vasta sezione di ritratti di personaggi influenti, nouveau genre artistique qui est né avec Alexandre le Grand.

Organismes idéaux, organismes extrêmes vous permet de vérifier le développement de nouvelles formes de disciplines artistiques de la vie quotidienne, positions avec dynamique.

La sixième section, “Divinité”, aborde la place d’un sujet important et présente des œuvres d’une beauté extraordinaire, y compris la Minerve d’Arezzo, le médaillon avec le buste d’Athéna et de la Tête d’Aphrodite.

Cecilia Chiavisteli

Par le nombre 57 – Année II 25/03/2015

Puissance et de pathos. Bronzes du monde hellénistique

Jusqu’au 21 Juin 2015

Palais Strozzi – Florence

Info: 055 2645155 – http://www.palazzostrozzi.org

cb

Apoxyomène

L’Apoxyomène (en grec ancienἀποξυόμενος / apoxuómenos, de ἀποξὐω / apoxúô, « racler, gratter ») est un marbre d’après Lysippe, représentant, comme son nom l’indique, un athlète nu se raclant la peau avec un strigile. Il est conservé au musée Pio-Clementino (musées du Vatican) sous le numéro Inv. 1185.

Sommaire

[masquer]

Découverte

En 1849, dans le quartier romain du Trastevere, des ouvriers découvrent dans les ruines de ce qu’on croit alors être des thermes romains la statue d’un jeune homme nu se raclant avec un strigile[1]. Son premier commentateur, l’architecte et antiquaire Luigi Canina, l’identifie comme une copie du sculpteur grec Polyclète[2], mais dès l’année suivante, l’archéologue allemand August Braun[3] y reconnaît une copie d’un type en bronze de Lysippe (vers 330–320 av. J.-C.), que nous connaissons uniquement par une mention de Pline l’Ancien dans son Histoire naturelle : « [Lysippe] réalisa, comme nous l’avons dit, le plus grand nombre de statues de tous, avec un art très fécond, et parmi elles, un athlète en train de se nettoyer avec un strigile (destringens se)[4]. »

Le type est fameux dès l’Antiquité : toujours selon Pline, la statue est consacrée par le général Marcus Agrippa devant les thermes qui portent son nom. L’empereur Tibère, grand admirateur de la statue, la fait enlever et transporter dans sa chambre. « Il en résulta une telle fronde du peuple romain », raconte Pline, « qu’il réclama dans les clameurs du théâtre qu’on restituât l’Apoxyomène et que le prince, malgré son amour, le restitua[4]. »

Braun se fonde d’une part sur la pose de la statue, d’autre part sur les remarques de Pline sur le canon lysippéen, plus élancé que celui de Polyclète[5] : effectivement, la tête est plus petite par rapport au corps, plus fin — il faut toutefois remarquer qu’à l’époque, le Doryphore n’avait pas encore été reconnu comme tel[6]. Dans l’ensemble, les arguments avancés par Braun sont assez faibles[7] : d’abord, l’athlète au strigile est un type commun dans l’Antiquité. Ensuite, le canon élancé, bien qu’utilisé de manière intensive par Lysippe et son école, n’est pas spécifique à cet artiste : on le retrouve par exemple dans les combattants de la frise du Mausolée d’Halicarnasse[8]. Cependant, malgré des contestations, l’attribution à Lysippe est largement admise aujourd’hui[9].

La statue jouit d’une grande popularité dès sa découverte. Elle est restaurée par le sculpteur italien Pietro Tenerani qui complète les doigts de la main droite, le bout du nez, restitue le strigile disparu de la main gauche et cache le sexe de l’athlète par une feuille de vigne[10] — ces restaurations ont été supprimées récemment. De nombreux moulages en sont réalisés. Jacob Burckhardt la cite dans son Cicerone (guide de Rome) de 1865[11].

Description

La statue, réalisée en marbre du Pentélique est légèrement plus grande que nature : elle mesure 2,05 mètres[12]. Elle représente un jeune homme nu, debout, raclant la face postérieure de l’avant-bras droit à l’aide d’un strigile tenu de la main gauche. Il hoche légèrement la tête et regarde devant lui. Un tronc d’arbre sert d’étai à la jambe gauche ; un autre étai, aujourd’hui brisé, faisait supporter le poids du bras droit tendu sur la jambe droite.

La statue frappe d’abord par sa composition : elle n’est plus uniquement frontale, comme dans le Doryphore ou le Discobole. Le bras tendu à angle droit de l’athlète oblige le spectateur, s’il veut bien saisir le mouvement, à se déplacer sur les côtés. Elle se distingue également par l’emploi du contrapposto (« déhanché ») : le poids du corps repose sur la seule jambe gauche, la droite étant légèrement avancée et repliée. De ce fait, les hanches sont orientées vers la gauche, alors que les épaules sont tournées dans le sens inverse, suivant le mouvement du bras droit, créant ainsi un mouvement de torsion que le spectateur ne peut pleinement saisir qu’en reproduisant lui-même la pose. La musculature est rendue de manière moins marquée que chez Polyclète. Alors que le torse représente traditionnellement le morceau de bravoure du sculpteur, il est ici partiellement dissimulé par la position des bras.

La tête frappe par sa petite taille : elle représente un huitième du corps entier, contre un septième dans le canon polyclétéen. L’historienne de l’art Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway juge même l’effet « presque comique[13] ». Autre nouveauté, la tête est traitée comme un portrait : la chevelure est représentée en désordre, le front est marqué et les yeux, enfoncés. Pour R. R. R. Smith, ces caractéristiques rendent la tête plus vivante[14], mais Ridgway les considère comme des défauts attribuables au copiste, ou à une erreur de présentation de la statue : elle aurait pu être présentée sur une base surélevée[15].

Copies et variantes

L’Apoxyomène du Vatican est le seul exemplaire entier en marbre de ce type[16]. Un torse très abîmé des réserves du Musée national romain, d’origine inconnue, a été reconnu en 1967 comme une réplique, mais dont la pose est inversée. Un autre torse, décorant la façade du Bâtiment M (probablement une bibliothèque) à Sidé, en Pamphylie, a été identifiée comme une variante en 1973. Enfin, un torse de proportions beaucoup plus réduites, découvert à Fiesole (Toscane) a été rattaché à l’Apoxyomène, mais son authenticité a été contestée[17]. Cette relative absence de copies s’explique mal : Rome comptait plusieurs ateliers de copistes[18]. Par ailleurs, aucun obstacle technique ne semble avoir pu empêcher la réalisation de moulages, Pline ne mentionnant aucune dorure.

Un type différent a été découvert en 1898 à Éphèse ; la statue, en bronze, est actuellement conservée au musée d’histoire de l’art de Vienne (Inv. 3168). Haute de 1,92 mètre, cette copie romaine représente un athlète à la musculature puissante qui, ayant terminé de se racler le corps, nettoie son strigile : il le tient de la main droite et enlève la sueur et la poussière du racloir avec l’index et le pouce de la main gauche ; la position des jambes et plus généralement le mouvement de torsion sont inversés par rapport à l’Apoxyomène du Vatican. Contrairement à ce dernier, qui semble regarder dans la vague, l’athlète d’Éphèse est concentré sur sa tâche.

Un autre exemplaire en bronze, l’Apoxyomène de Croatie a été découvert en 1996 en mer Adriatique, remonté en 1999 et restauré jusqu’en 2005[19]. Son apparence est proche de l’Apoxyomène d’Éphèse et de la tête se trouvant au musée d’art Kimbell de Fort Worth (Texas). La particularité de l’Apoxyomène de Croatie est d’être pratiquement complet (il lui manque l’auriculaire de la main gauche), dans un état de conservation exceptionnel et d’avoir encore sa plinthe antique[20].

http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apoxyom%C3%A8ne

http://www.laterrazzadimichelangelo.it/news/la-bellezza-nei-bronzi-ellenistici-in-mostra-a-palazzo-strozzi/?lang=fr

http://www.giacobbegiusti.com

Giacobbe Giusti, Zurück zur Klassik

Giacobbe Giusti, Zurück zur Klassik

Die Statue eines Faustkämpfers aus Rom (Quirinal), Bronze, 2. Hälfte des vierte Jahrhunderts v. Chr. oder des dritten Jahrhunderts v. Chr. ist hier zu sehen.

Foto: Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Liebighaus

Das Frankfurter Liebieghaus präsentiert erlesene griechische Skulpturen unter dem Titel “Zurück zur Klassik”: Hier ein geflügelter Kopf des Hypnos, Original des vierten Jahrhunderts v. Chr. oder römische Wiederholung des ersten Jahrhunderts v. Chr..

Foto: Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Liebighaus

Die Statue eines Faustkämpfers aus Rom (Quirinal), Bronze, 2. Hälfte des vierte Jahrhunderts v. Chr. oder des dritten Jahrhunderts v. Chr. ist hier zu sehen.

Foto: Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Liebighaus

Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770–1840) schuf den Kopf des rechten Vorkämpfers (l.) als Ergänzung für den Westgiebel des Aphaia-Tempels von Aigina zwischen 1812 und 1818. (l.) Rechts ist der Gegner des rechten Vorkämpfers ausgestellt (480/479 v. Chr.).

Foto: Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Liebighaus

Der Kopf des Apollon Sauroktonos des Praxiteles, späthellenistische Kopie (vor der Mitte des ersten Jahrhunderts v. Chr.) nach einem Vorbild um 350 v. Chr. ist ebenfalls ein Exponat.

Foto: © Staatliche Kunstsammlungen

Buchrezension

Zurück zur Klassik

Vinzenz Brinkmann (Hrsg.)

– Ein neuer Blick auf das alte Griechenland

München: Hirmer Verlag 2013, 380 S., 518 farb. Abb., 75 Farbtafeln, 30 S/W-Abb., 49,90 Euro

Die griechische Klassik steht für eine Zeit voller Innovationen und prägte die spätere europäische Kultur entscheidend. Ob Architektur, philosophische Schriften, Dichtungen oder Kunst: Die kulturellen Erzeugnisse des 5. und 4. Jh. v.Chr. in Griechenland wurden von allen darauffolgenden Epochen rezipiert, weil sie als vorbildlich und normativ, eben als klassisch galten.

Der an jener Zeit Interessierte wird sowohl bei seinem Besuch der Ausstellung »Zurück zur Klassik« in der Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung in Frankfurt am Main als auch beim Lesen des gleichnamigen Katalogs überrascht sein: Fundierte Beiträge und 518 Abbildungen von mehr als 80 Originalen machen ihm bewusst, wie tiefgreifend das heutige Bild der griechischen Klassik während der vergangenen 2500 Jahre eingeschränkt und verzerrt wurde. Viele Kunstwerke wie z.B. Malereien gingen aufgrund ihrer Beschaffenheit verloren, andere wurden wiederum ganz bewusst selektiert und zerstört.

Renommierte Wissenschaftler stellen aktuelle Ergebnisse vor – von der Rekonstruktionsarbeit an den berühmten Bronzen von Riace bis hin zur Malerei des 5. und 4. Jh. v.Chr. Anhand der Originale lernt der Leser jene Epoche noch einmal neu kennen, weil sie weniger von Idealen, vielmehr vom Leben selbst erzählen und unerwartet realistisch erscheinen. Der Katalog bietet ein neues, anderes, vor allem aber ein unverfälschtes Bild zur griechischen Klassik.

Leoni Hellmayr

Giacobbe Giusti, Power and Pathos

Giacobbe Giusti, Power and Pathos

Giacobbe Giusti, Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World

Giacobbe Giusti, Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World

First-Ever Major Exhibition of Hellenistic Bronze Sculptures Will Travel Internationally

The Getty, the Palazzo Strozzi, and the National Gallery of Art collaborate with the Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici della Toscana to present

Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World

March 2015 – March 2016

in Florence, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C.

Amy Hood

Getty Communications

(310) 440-6427

ahood@getty.edu

From sculptures known since the Renaissance, such as the Arringatore (Orator) from Sanguineto (in the collection of the Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Florence), to spectacular recent discoveries that have never before been exhibited in the United States, the exhibition is the most comprehensive museum survey of Hellenistic bronzes ever organized. In each showing of the exhibition, recent finds—many salvaged from the sea—will be exhibited for the first time alongside well-known works. The works of art on view will range in scale from statuettes, busts and heads to life-size figures and herms.

Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World is especially remarkable for bringing together works of art that, because of their rarity, are usually exhibited in isolation. When viewed in proximity to one another, the variety of styles and techniques employed by ancient sculptors is emphasized to greater effect, as are the varying functions and histories of the bronze sculptures.

Bronze was a material well-suited to reproduction, and the exhibition provides an unprecedented opportunity to see objects of the same type, and even from the same workshop together for the first time.

The travel schedule for Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World is:

- Palazzo Strozzi, Florence, Italy

March 14 – June 21, 2015

http://www.palazzostrozzi.org - J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA

July 28 – November 1, 2015

http://www.getty.edu - National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

December 6, 2015 – March 20, 2016

http://www.nga.gov

This exhibition is curated by Jens Daehner and Kenneth Lapatin of the J. Paul Getty Museum and co-organized by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; the Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi, Florence; and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; with the participation of Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici della Toscana. It is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities.

Image: Portrait of a Man, about 100 B.C. Bronze, white paste, and dark stone, 32.5 x 22 x 22 cm. Courtesy of the National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Photo: Marie Mauzy/Art Resource, NY

The J. Paul Getty Trust is an international cultural and philanthropic institution devoted to the visual arts that includes the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Getty Research Institute, the Getty Conservation Institute, and the Getty Foundation. The J. Paul Getty Trust and Getty programs serve a varied audience from two locations: the Getty Center in Los Angeles and the Getty Villa in Malibu.

The J. Paul Getty Museum collects in seven distinct areas, including Greek and Roman antiquities, European paintings, drawings, manuscripts, sculpture and decorative arts, and photographs gathered internationally. The Museum’s mission is to make the collection meaningful and attractive to a broad audience by presenting and interpreting the works of art through educational programs, special exhibitions, publications, conservation, and research.

Visiting the Getty Center

The Getty Center is open Tuesday through Friday and Sunday from 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., and Saturday from 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. It is closed Monday and most major holidays. Admission to the Getty Center is always free. Parking is $15 per car, but reduced to $10 after 5 p.m. on Saturdays and for evening events throughout the week. No reservation is required for parking or general admission. Reservations are required for event seating and groups of 15 or more. Please call (310) 440-7300 (English or Spanish) for reservations and information. The TTY line for callers who are deaf or hearing impaired is (310) 440-7305. The Getty Center is at 1200 Getty Center Drive, Los Angeles, California.

Additional information is available at http://www.getty.edu.

Sign up for e-Getty at http://www.getty.edu/subscribe to receive free monthly highlights of events at the Getty Center and the Getty Villa via e-mail, or visit http://www.getty.edu for a complete calendar of public programs.

http://news.getty.edu/press-materials/press-releases/hellenistic-bronze-sculptures-travel-internationally-.htm

http://www.giacobbegiusti.com

Giacobbe Giusti, Chimera of Arezzo

Giacobbe Giusti, Chimera of Arezzo

Chimera of Arezzo

|

|

| Year | c. 400 BC |

|---|---|

| Type | bronze |

The bronze “Chimera of Arezzo” is one of the best known examples of the art of the Etruscans. It was found in Arezzo, an ancient Etruscan and Roman city in Tuscany, in 1553 and was quickly claimed for the collection of the Medici Grand Duke of Tuscany Cosimo I, who placed it publicly in the Palazzo Vecchio, and placed the smaller bronzes from the trove in his own studiolo at Palazzo Pitti, where “the Duke took great pleasure in cleaning them by himself, with some goldsmith’s tools,” Benvenuto Cellini reported in his autobiography. The Chimera is still conserved in Florence, now in the Archaeological Museum. It is approximately 80 cm in height.[1]

In Greek mythology the monstrous Chimera ravaged its homeland, Lycia, until it was slain by Bellerophon. The goat head of the Chimera has a wound inflicted by this Greek hero. Based on the cowering, representation of fear, and the wound inflicted, this sculpture may have been part of a set that would have included a bronze sculpture of Bellerophon. This bronze was at first identified as a lion by its discoverers in Arezzo, for its tail, which would have taken the form of a serpent, is missing. It was soon recognized as representing the chimera of myth and in fact, among smaller bronze pieces and fragments brought to Florence, a section of the tail was soon recovered, according to Giorgio Vasari. The present bronze tail is an 18th-century restoration.

The Chimera was one of a hoard of bronzes that had been carefully buried for safety some time in antiquity. They were discovered by accident, when trenches were being dug just outside the Porta San Laurentino in the city walls. A bronze replica now stands near the spot.

Inscribed on its right foreleg is an inscription which has been variously read, but most recently is agreed to be TINSCVIL, showing that the bronze was a votive object dedicated to the supreme Etruscan god of day, Tin or Tinia. The original statue is estimated to have been created around 400 BC.

In 2009 and 2010 the statue traveled to the United States where it was displayed at the Getty Villa in Malibu, California.[1][2][3]

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chimera_of_Arezzo

Chimera di Arezzo

| Chimera di Arezzo | |

|---|---|

| Autore | sconosciuto |

| Data | seconda metà o fine V sec. a.C. circa |

| Materiale | bronzo |

| Altezza | 65 cm |

| Ubicazione | Museo archeologico nazionale, Firenze

|

La Chimera di Arezzo è un bronzo etrusco, probabilmente opera di un équipe di artigiani attiva nella zona di Arezzo, che combinava modello e forma stilistica di ascendenza greca o italiota all’abilità tecnica fornita da maestranze etrusche[1]. È conservata presso il Museo archeologico nazionale di Firenze ed è alta 65 cm.

Storia

La sua datazione viene fatta risalire ad un periodo compreso tra l’ultimo quarto del V e i primi decenni del IV secolo a.C. Faceva parte di un gruppo di bronzi sepolti nell’antichità per poterli preservare.

Con l’aiuto di Pegaso, Bellerofonte riuscì a sconfiggere Chimera con le sue stesse terribili armi: immerse la punta del suo giavellotto nelle fauci della belva, il fuoco che ne usciva sciolse il piombo che uccise l’animale.

Si tratta di una statua di bronzo rinvenuta il 15 novembre 1553 in Toscana,La chimera è stata representata in modi diversi.è stata creata per incudere peura e terrore. precisamente nella città d’Arezzo durante la costruzione di fortificazioni medicee alla periferia della cittadina, fuori da Porta San Lorentino (dove oggi si trova una replica in bronzo). Venne subito reclamata dal granduca di Toscana Cosimo I de’ Medici per la sua collezione, il quale la espose pubblicamente presso il Palazzo Vecchio, nella sala di Leone X. Venne poi trasferita presso il suo studiolo di Palazzo Pitti, in cui, come riportato da Benvenuto Cellini nella sua autobiografia, “il duca ricavava grande piacere nel pulirla personalmente con attrezzi da orafo”.

Dalle notizie del ritrovamento, presenti nell’Archivio di Arezzo, risulta che questo bronzo venne identificato inizialmente con un leone poiché la coda, rintracciata in seguito da Giorgio Vasari, non era ancora stata trovata e fu ricomposta solo nel XVIII secolo grazie ad un restauro visibile ancora oggi. Vasari nei suoi Ragionamenti sopra le invenzioni da lui dipinte in Firenze nel palazzo di loro Altezze Serenissime[2] risponde così ad un interlocutore che gli domanda se si tratta proprio della Chimera di Bellerofonte

| « Signor sì, perché ce n’è il riscontro delle medaglie che ha il Duca mio signore, che vennono da Roma con la testa di capra appiccicata in sul collo di questo leone, il quale come vede V.E., ha anche il ventre di serpente, e abbiamo ritrovato la coda che era rotta fra que’ fragmenti di bronzo con tante figurine di metallo che V.E. ha veduto tutte, e le ferite che ella ha addosso, lo dimostrano, e ancora il dolore, che si conosce nella prontezza della testa di questo animale… » |

Il restauro alla coda è però un restauro sbagliato: il serpente doveva avventarsi minacciosamente contro Bellerofonte e non mordere un corno della testa della capra.

Nel 1718 venne poi trasportata nella Galleria degli Uffizi e in seguito fu trasferita nuovamente, insieme all’Idolino e ad altri bronzi classici, presso il Palazzo della Crocetta, dove si trova tuttora, nell’odierno Museo archeologico di Firenze.

Descrizione e stile

Nella mitologia greca la chimera (il cui nome in greco significa letteralmente capra) era un mostro che sputava fuoco, talvolta alato, con il corpo e la testa di leone, la coda a forma di serpente e con una testa di capra nel mezzo della schiena, che terrorizzava la terra della Licia. Venne uccisa da Bellerofonte in un epico scontro con l’aiuto del cavallo alato Pegaso.

La Chimera di Arezzo raffigura il mostro uccidente, che si ritrae di lato, e volge la testa in atteggiamento drammatico di notevole sofferenza, con la bocca spalancata e la criniera irta. La testa di capra sul dorso è già reclinata e morente a causa delle ferite ricevute. Il corpo è modellato in maniera da mostrare le costole del torace, mentre le vene solcano il ventre e le gambe. Probabilmente, la Chimera faceva parte di un gruppo con Bellerofonte e Pegaso ma non si può escludere completamente l’ipotesi che si trattasse di un’offerta votiva a sé stante. Quest’ipotesi sembra essere confermata dalla presenza di un’iscrizione sulla branca anteriore destra, in cui vi si legge la scritta TINSCVIL o TINS’VIL (TLE^2 663), che significa “donata al dio Tin“, supremo dio etrusco del giorno.

La Chimera presenta elementi arcaici, come la criniera schematica e il muso leonino simile a modelli greci del V secolo a.C., mentre il corpo è di una secchezza austera. Altri tratti sono invece più spiccatamente naturalistici, come l’accentuazione drammatica della posa e la sofisticata postura del corpo e delle zampe. Questa commistione è tipica del gusto etrusco della prima metà del IV secolo a.C. e attraverso il confronto con leoni funerari coevi si è giunti a una datazione attorno al 380–360 a.C. È da osservare il particolare della criniera, molto lavorata, e che riproduce abbastanza fedelmente (per l’epoca) l’aspetto naturale della fiera.

http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chimera_di_Arezzo

https://softbrightness.wordpress.com/

Giacobbe Giusti, The Celts

Giacobbe Giusti, The Celts

Celts

The Wandsworth Shield-boss, in the plastic style, found in London

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

The Celts (/ˈkɛlts/, occasionally /ˈsɛlts/, see pronunciation of Celtic) were people in Iron Age and Medieval Europe who spoke Celtic languages and had cultural similarites,[1] although the relationship between ethnic, linguistic and cultural factors in the Celtic world remains uncertain and controversial.[2] The exact geographic spread of the ancient Celts is also disputed; in particular, the ways in which the Iron Age inhabitants of Great Britain and Ireland should be regarded as Celts has become a subject of controversy.[1][2][3][4]

The history of pre-Celtic Europe remains very uncertain. According to one theory, the common root of the Celtic languages, a language known as Proto-Celtic, arose in the Late Bronze Age Urnfield culture of Central Europe, which flourished from around 1200 BC.[5] In addition, according to a theory proposed in the 19th century, the first people to adopt cultural characteristics regarded as Celtic were the people of the Iron Age Hallstatt culture in central Europe (c. 800–450 BC), named for the rich grave finds in Hallstatt, Austria.[5][6] Thus this area is sometimes called the ‘Celtic homeland’. By or during the later La Tène period (c. 450 BC up to the Roman conquest), this Celtic culture was supposed to have expanded by diffusion or migration to the British Isles (Insular Celts), France and The Low Countries (Gauls), Bohemia, Poland and much of Central Europe, the Iberian Peninsula (Celtiberians, Celtici, Lusitanians and Gallaeci) and Italy (Canegrate, Golaseccans and Cisalpine Gauls)[7] and, following the Gallic invasion of the Balkans in 279 BC, as far east as central Anatolia (Galatians).[8]

The earliest undisputed direct examples of a Celtic language are the Lepontic inscriptions, beginning in the 6th century BC.[9] Continental Celtic languages are attested almost exclusively through inscriptions and place-names. Insular Celtic is attested beginning around the 4th century AD through Ogham inscriptions, although it was clearly being spoken much earlier. Celtic literary tradition begins with Old Irish texts around the 8th century. Coherent texts of Early Irish literature, such as the Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle Raid of Cooley), survive in 12th-century recensions.

By the mid 1st millennium AD, with the expansion of the Roman Empire and the Great Migrations (Migration Period) of Germanic peoples, Celtic culture and Insular Celtic had become restricted to Ireland, the western and northern parts of Great Britain (Wales, Scotland, and Cornwall), the Isle of Man, and Brittany. Between the 5th and 8th centuries, the Celtic-speaking communities in these Atlantic regions emerged as a reasonably cohesive cultural entity. They had a common linguistic, religious, and artistic heritage that distinguished them from the culture of the surrounding polities.[10] By the 6th century, however, the Continental Celtic languages were no longer in wide use.

Insular Celtic culture diversified into that of the Gaels (Irish, Scottish and Manx) and the Brythonic Celts (Welsh, Cornish, and Bretons) of the medieval and modern periods. A modern “Celtic identity” was constructed as part of the Romanticist Celtic Revival in Great Britain, Ireland, and other European territories, such as Portugal and Spanish Galicia.[11] Today, Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Welsh, and Breton are still spoken in parts of their historical territories, and Cornish and Manx are undergoing a revival.

Contents

Names and terminology

Celtic stele from Galicia, 2nd century AD: “APANA·AMBO / LLI·

F(ilia)·CELTICA / SUPERTAM(arica)· /

(j) MIOBRI· / AN(norum)·

XXV·H(ic)·S(ita)·E(st)· / APANUS·FR(ater)·

F(aciendum)·C(uravit)”

The first recorded use of the name of Celts – as Κελτοί – to refer to an ethnic group was by Hecataeus of Miletus, the Greek geographer, in 517 BC,[12] when writing about a people living near Massilia (modern Marseille).[13] According to the testimony of Julius Caesar and Strabo, the Latin name Celtus (pl. Celti or Celtae) and the Greek Κέλτης (pl. Κέλται) or Κελτός (pl. Κελτοί) were borrowed from a native Celtic tribal name.[14][15] Pliny the Elder cited its use in Lusitania as a tribal surname,[16] which epigraphic findings have confirmed.[17][18]

Latin Gallus (pl. Galli) might also stem from a Celtic ethnic or tribal name originally, perhaps one borrowed into Latin during the Celtic expansions into Italy during the early 5th century BC. Its root may be the Common Celtic *galno, meaning “power, strength”, hence Old Irish gal “boldness, ferocity” and Welsh gallu “to be able, power”. The tribal names of Gallaeci and the Greek Γαλάται (Galatai, Latinized Galatae; see the region Galatia in Anatolia) most probably go with the same origin.[19] The suffix -atai might be an Ancient Greek inflection.[20] Classical writers did not apply the terms Κελτοί or “Celtae” to the inhabitants of Britain or Ireland,[1][2][3] which has led to some scholars preferring not to use the term for the Iron Age inhabitants of those islands.[1][2][3][4]

Celt is a modern English word, first attested in 1707, in the writing of Edward Lhuyd, whose work, along with that of other late 17th-century scholars, brought academic attention to the languages and history of the early Celtic inhabitants of Great Britain.[21] The English form Gaul (first recorded in the 17th century) and Gaulish come from the French Gaule and Gaulois, a borrowing from Frankish *Walholant, “Land of foreigners or Romans” (see Gaul: Name), the root of which is Proto-Germanic *walha-, “foreigner”’, or “Celt”, whence the English word Welsh (Anglo-Saxon wælisċ < *walhiska-), South German welsch, meaning “Celtic speaker”, “French speaker” or “Italian speaker” in different contexts, and Old Norse valskr, pl. valir, “Gaulish, French”). Proto-Germanic *walha is derived ultimately from the name of the Volcae,[22] a Celtic tribe who lived first in the South of Germany and emigrated then to Gaul.[23] This means that English Gaul, despite its superficial similarity, is not actually derived from Latin Gallia (which should have produced **Jaille in French), though it does refer to the same ancient region.

Celtic refers to a family of languages and, more generally, means “of the Celts” or “in the style of the Celts”. Several archaeological cultures are considered Celtic in nature, based on unique sets of artefacts. The link between language and artefact is aided by the presence of inscriptions.[24] (See Celtic (disambiguation) for other applications of the term.) The relatively modern idea of an identifiable Celtic cultural identity or “Celticity” generally focuses on similarities among languages, works of art, and classical texts,[25] and sometimes also among material artefacts, social organisation, homeland and mythology.[26] Earlier theories held that these similarities suggest a common racial origin for the various Celtic peoples, but more recent theories hold that they reflect a common cultural and language heritage more than a genetic one. Celtic cultures seem to have been widely diverse, with the use of a Celtic language being the main thing they have in common.[1]

Today, the term Celtic generally refers to the languages and respective cultures of Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Cornwall, the Isle of Man, and Brittany, also known as the Celtic nations. These are the regions where four Celtic languages are still spoken to some extent as mother tongues. The four are Irish Gaelic, Scottish Gaelic, Welsh, and Breton; plus two recent revivals, Cornish (one of the Brythonic languages) and Manx (one of the Goidelic languages). There are also attempts to reconstruct the Cumbric language (a Brythonic language from North West England and South West Scotland). Celtic regions of Continental Europe are those whose residents claim a Celtic heritage, but where no Celtic language has survived; these areas include the western Iberian Peninsula, i.e. Portugal, and north-central Spain (Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, Castile and León, Extremadura).[27] (See also: Modern Celts.)

Continental Celts are the Celtic-speaking people of mainland Europe and Insular Celts are the Celtic-speaking peoples of the British and Irish islands and their descendants. The Celts of Brittany derive their language from migrating insular Celts, mainly from Wales and Cornwall, and so are grouped accordingly.[28]

Origins

Overview of the Hallstatt and La Tène cultures:

The territories of some major Celtic tribes of the late La Tène period are labelled.

The Celtic languages form a branch of the larger Indo-European family. By the time speakers of Celtic languages enter history around 400 BC, they were already split into several language groups, and spread over much of Western continental Europe, the Iberian Peninsula, Ireland and Britain.

Some scholars think that the Urnfield culture of Western Middle Europe represents an origin for the Celts as a distinct cultural branch of the Indo-European family.[5] This culture was preeminent in central Europe during the late Bronze Age, from c. 1200 BC until 700 BC, itself following the Unetice and Tumulus cultures. The Urnfield period saw a dramatic increase in population in the region, probably due to innovations in technology and agricultural practices. The Greek historian Ephoros of Cyme in Asia Minor, writing in the 4th century BC, believed that the Celts came from the islands off the mouth of the Rhine and were “driven from their homes by the frequency of wars and the violent rising of the sea”.

The spread of iron-working led to the development of the Hallstatt culture directly from the Urnfield (c. 700 to 500 BC). Proto-Celtic, the latest common ancestor of all known Celtic languages, is considered by this school of thought to have been spoken at the time of the late Urnfield or early Hallstatt cultures, in the early 1st millennium BC. The spread of the Celtic languages to Iberia, Ireland and Britain would have occurred during the first half of the 1st millennium BC, the earliest chariot burials in Britain dating to c. 500 BC. Other scholars see Celtic languages as covering Britain and Ireland, and parts of the Continent, long before any evidence of “Celtic” culture is found in archaeology. Over the centuries the language(s) developed into the separate Celtiberian, Goidelic and Brythonic languages.

The Hallstatt culture was succeeded by the La Tène culture of central Europe, which was overrun by the Roman Empire, though traces of La Tène style are still to be seen in Gallo-Roman artefacts. In Britain and Ireland La Tène style in art survived precariously to re-emerge in Insular art. Early Irish literature casts light on the flavour and tradition of the heroic warrior elites who dominated Celtic societies. Celtic river-names are found in great numbers around the upper reaches of the Danube and Rhine, which led many Celtic scholars to place the ethnogenesis of the Celts in this area. A recent book about an ancient site in northern Germany, concludes that it was the most significant Celtic sacred site in Europe. It is called the “Externsteine”, the strange carvings and astronomical orientation of the chambers of this site are presented as solid evidence for a Celtic origin. In view of the large number of sites excavated in recent years in Germany, and formally defined as ‘Celtic”, Pryor’s research appears to be on solid ground. (Damien Pryor, The Externsteine, 2011, Threshold Publishing, ISBN 978-0-9581341-7-0 )

Diodorus Siculus and Strabo both suggest that the heartland of the people they called Celts was in southern France. The former says that the Gauls were to the north of the Celts, but that the Romans referred to both as Gauls (in linguistic terms the Gauls were certainly Celts). Before the discoveries at Hallstatt and La Tène, it was generally considered that the Celtic heartland was southern France, see Encyclopædia Britannica for 1813.

Linguistic evidence