Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Leonardo da Vinci, Ginevra de’ Benci, c. 1474

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Giorgione, Adoration of the Shepherds, c. 1500

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

El Greco, Saint Martin and the Beggar, c. 1597-1599[22]

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Giorgione and Titian, Portrait of a Venetian Nobleman, c. 1507

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Mill, 1648

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Peter Paul Rubens, Germanicus and Agrippina, 1614

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Édouard Manet, The Railway, 1872

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Édouard Manet, The Plum,1878

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Claude Monet, The Artist’s Garden at Vétheuil, 188

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Vincent van Gogh, Self-portrait, August 1889

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

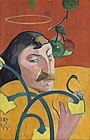

Paul Gauguin, Self-portrait, 1889

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

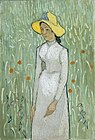

Vincent van Gogh, Woman in White, 1890

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Claude Monet, Rouen Cathedral, West Facade, Sunlight, 1894

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Édouard Manet, The Old Musician, 1862

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Henri Matisse, Open Window, Collioure, 1905

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Eugène Delacroix, Columbus and His Son at La Rábida, 1838

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Paul Cézanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat, 1888–1890

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Pablo Picasso, Family of Saltimbanques, 1905

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Pablo Picasso, Still Life, 1918

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

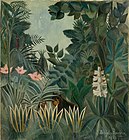

Henri Rousseau, The Equatorial Jungle, 1909

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

|

|

| Established | 1937 |

|---|---|

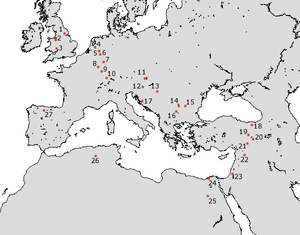

| Location | National Mall between 3rd and 9th Streets at Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DC, 20565, National Mall, Washington, D.C. |

| Coordinates | 38.89147°N 77.02001°W |

| Visitors | 5,232,277 (2017) – Ranked seventh globally [1] |

| Director | Earl A. Powell III |

| Public transit access |

|

| Website | www.nga.gov |

The National Gallery of Art, and its attached Sculpture Garden, is a national art museum in Washington, D.C., located on the National Mall, between 3rd and 9th Streets, at Constitution AvenueNW. Open to the public and free of charge, the museum was privately established in 1937 for the American people by a joint resolution of the United States Congress. Andrew W. Mellon donated a substantial art collection and funds for construction. The core collection includes major works of art donated by Paul Mellon, Ailsa Mellon Bruce, Lessing J. Rosenwald, Samuel Henry Kress, Rush Harrison Kress, Peter Arrell Browne Widener, Joseph E. Widener, and Chester Dale. The Gallery’s collection of paintings, drawings, prints, photographs, sculpture, medals, and decorative arts traces the development of Western Art from the Middle Ages to the present, including the only painting by Leonardo da Vinci in the Americas and the largest mobile created by Alexander Calder.

The Gallery’s campus includes the original neoclassical West Building designed by John Russell Pope, which is linked underground to the modern East Building, designed by I. M. Pei, and the 6.1-acre (25,000 m2) Sculpture Garden. The Gallery often presents temporary special exhibitions spanning the world and the history of art. It is one of the largest museums in North America.

History

National Gallery of Art

Pittsburgh banker (and Treasury Secretary from 1921 until 1932) Andrew W. Mellonbegan gathering a private collection of old masterpaintings and sculptures during World War I. During the late 1920s, Mellon decided to direct his collecting efforts towards the establishment of a new national gallery for the United States.

In 1930, partly for tax reasons, Mellon formed the A. W. Mellon Educational and Charitable Trust, which was to be the legal owner of works intended for the gallery. In 1930–1931, the Trust made its first major acquisition, 21 paintings from the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg as part of the Soviet sale of Hermitage paintings, including such masterpieces as Raphael‘s Alba Madonna, Titian‘s Venus with a Mirror, and Jan van Eyck‘s Annunciation.

In 1929 Mellon had initiated contact with the recently appointed Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, Charles Greeley Abbot. Mellon was appointed in 1931 as a Commissioner of the Institution’s National Gallery of Art. When the director of the Gallery retired, Mellon asked Abbot not to appoint a successor, as he proposed to endow a new building with funds for expansion of the collections.

However, Mellon’s trial for tax evasion, centering on the Trust and the Hermitage paintings, caused the plan to be modified. In 1935, Mellon announced in The Washington Star, his intention to establish a new gallery for old masters, separate from the Smithsonian. When asked by Abbot, he explained that the project was in the hands of the Trust and that its decisions were partly dependent on “the attitude of the Government towards the gift”.

In January 1937, Mellon formally offered to create the new Gallery. On his birthday, 24 March 1937, an Act of Congress accepted the collection and building funds (provided through the Trust), and approved the construction of a museum on the National Mall.

The new gallery was to be effectively self-governing, not controlled by the Smithsonian, but took the old name “National Gallery of Art” while the Smithsonian’s gallery would be renamed the “National Collection of Fine Arts” (now the Smithsonian American Art Museum).[2][3][4]

Designed by architect John Russell Pope, the new structure was completed and accepted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on behalf of the American people on March 17, 1941. Neither Mellon nor Pope lived to see the museum completed; both died in late August 1937, only two months after excavation had begun. At the time of its inception it was the largest marble structure in the world. The museum stands on the former site of the Baltimore and Potomac Railroadstation, where in 1881 a disgruntled office seeker, Charles Guiteau, shot President James Garfield (see James A. Garfield assassination).[5]

As anticipated by Mellon, the creation of the National Gallery encouraged the donation of other substantial art collections by a number of private donors. Founding benefactors included such individuals as Paul Mellon, Samuel H. Kress, Rush H. Kress, Ailsa Mellon Bruce, Chester Dale, Joseph Widener, Lessing J. Rosenwaldand Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch.

The Gallery’s East Building was constructed in the 1970s on much of the remaining land left over from the original congressional action. Andrew Mellon’s children, Paul Mellon and Ailsa Mellon Bruce, funded the building. Designed by architect I. M. Pei, the contemporary structure was completed in 1978 and was opened on June 1 of that year by President Jimmy Carter. The new building was built to house the Museum’s collection of modern paintings, drawings, sculptures, and prints, as well as study and research centers and offices. The design received a National Honor Award from the American Institute of Architects in 1981.

The final addition to the complex is the National Gallery of Art Sculpture Garden. Completed and opened to the public on May 23, 1999, the location provides an outdoor setting for exhibiting a number of pieces from the Museum’s contemporary sculpture collection.

Operations

The National Gallery of Art is supported through a private-public partnership. The United States federal government provides funds, through annual appropriations, to support the museum’s operations and maintenance. All artwork, as well as special programs, are provided through private donations and funds. The museum is not part of the Smithsonian Institution.

Noted directors of the National Gallery have included David E. Finley, Jr. (1938-1956), John Walker (1956–1968), and J. Carter Brown(1968–1993). Earl A. “Rusty” Powell III (since 1993) is the current director.

Entry to both buildings of the National Gallery of Art is free of charge. From Monday through Saturday, the museum is open from 10 a.m. – 5 p.m.; it is open from 11 – 6 p.m. on Sundays. It is closed on December 25 and January 1.[6]

Architecture

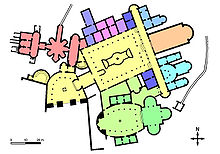

The museum comprises two buildings: the West Building (1941) and the East Building (1978) linked by an underground passage. The West Building, composed of pink Tennessee marble, was designed in 1937 by architect John Russell Pope in a neoclassical style (as is Pope’s other notable Washington, D.C. building, the Jefferson Memorial). Designed in the form of an elongated H, the building is centered on a domed rotunda modeled on the interior of the Pantheon in Rome. Extending east and west from the rotunda, a pair of skylit sculpture halls provide its main circulation spine. Bright garden courts provide a counterpoint to the long main axis of the building.

The West Building has an extensive collection of paintings and sculptures by European masters from the medieval period through the late 19th century, as well as pre-20th century works by American artists. Highlights of the collection include many paintings by Jan Vermeer, Rembrandt van Rijn, Claude Monet, Vincent van Gogh, and Leonardo da Vinci.

In contrast, the design of the East Building by architect I. M. Pei is geometrical, dividing the trapezoidal shape of the site into two triangles: one isosceles and the other a smaller right triangle. The space defined by the isosceles triangle came to house the museum’s public functions. The portion outlined by the right triangle became the study center. The triangles in turn became the building’s organized motif, echoed and repeated in every dimension.

The building’s central feature is a high atrium designed as an open interior court that is enclosed by a sculptural space spanning 16,000 square feet (1,500 m2). The atrium is centered on the same axis that forms the circulation spine for the West Building and is constructed in the same Tennessee marble.[7]

However, in 2005 the joints attaching the marble panels to the walls began to show signs of strain, creating a risk that panels might fall onto visitors below. In 2008, NGA officials decided that it had become necessary to remove and reinstall all of the panels. The renovation was completed in 2016.[8]

The East Building focuses on modern and contemporary art, with a collection including works by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Jackson Pollock, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Alexander Calder, a 1977 mural by Robert Motherwell and works by many other artists. The East Building also contains the main offices of the NGA and a large research facility, Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts (CASVA). Among the highlights of the East Building in 2012 was an exhibition of Barnett Newman‘s The Stations of the Cross series of 14 black and white paintings (1958–66).[9] Newman painted them after he had recovered from a heart attack; they are usually regarded as the peak of his achievement.[citation needed] The series has also been seen as a memorial to the victims of the Holocaust.[10]

The two buildings are connected by a walkway beneath 4th street, called “the Concourse” on the museum’s map. In 2008, the National Gallery of Art commissioned American artist Leo Villareal to transform the Concourse into an artistic installation. Today, Multiverse is the largest and most complex light sculpture by Villareal featuring approximately 41,000 computer-programmed LED nodes that run through channels along the entire 200-foot (61 m)-long space.[11] The concourse also includes the food court and a gift shop.

The final element of the National Gallery of Art complex, the Sculpture Garden was completed in 1999 after more than 30 years of planning. To the west of the West Building, on the opposite side of Seventh Street, the 6.1 acres (2.5 ha) Sculpture Garden was designed by landscape architect Laurie Olin[12] as an outdoor gallery for monumental modern sculpture.

The Sculpture Garden contains plantings of Native American species of canopy and flowering trees, shrubs, ground covers, and perennials. A circular reflecting pool and fountain form the center of its design, which arching pathways of granite and crushed stone complement. (The pool becomes an ice-skating rink during the winter.) The sculptures exhibited in the surrounding landscaped area include pieces by David Smith, Mark Di Suvero, Roy Lichtenstein, Sol LeWitt, Tony Smith, Roxy Paine, Joan Miró, Louise Bourgeois, and Hector Guimard.[13]

Renovations

The NGA’s West Building was renovated from 2007 to 2009. Although some galleries closed for periods of time, others remained open.[14]

After congressional testimony that the East Building suffered from “systematic structural failures”, NGA adopted a Master Renovations Plan in 1999. This plan established the timeline for closing the building, and planned for the renovation of the electronic security systems, elevators, and HVAC.[15] Space between the ceilings of existing galleries and the building’s skylights (which was never completed when the building was constructed in 1978)[15] would be renovated into two, 23-foot (7.0 m) high, hexagonal Tower Galleries. The galleries would have a combined 12,260 square feet (1,139 m2) of space and will be lit by skylights. A rooftop sculpture garden would also be added. NGA officials said that the Tower Galleries would probably house modern art, and the creation of a distinct “Rothko Room” was possible.

Beginning in 2011, NGA undertook an $85 million restoration of the East Building’s façade.[16] The East Building is clad in 3-inch (7.6 cm) thick pink marble panels. The panels are held about 2 inches (5.1 cm) away from the wall by stainless steel anchors. Gravity holds the panel in the bottom anchors (which are placed at each corner), while “button head” anchors (stainless steel posts with large, flat heads) at the top corners keep the panel upright. Mortar was used on the gravity anchors to level the stones. Joints of flexible colored neoprene were placed between the panels. This system was designed to allow each panel to hang independent of its neighbors, and NGA officials say they are not aware of any other panel system like it.

However, many panels were accidentally mortared together. Seasonal heating and cooling of the façade, infiltration of moisture, and shrinkage of the building’s structural concrete by 2 inches (5.1 cm) over time caused extensive damage to the façade. In 2005, regular maintenance showed that some panels were cracked or significantly damaged, while others leaned by more than 1 inch (2.5 cm) out from the building (threatening to fall).

The NGA hired the structural engineering firm Robert Silman Associates to determine the cause of the problem.[17] Although the Gallery began raising private funds to fix the issue,[17] eventually federal funding was used to repair the building.[16] In 2012, the NGA chose a joint venture, Balfour Beatty/Smoot, to complete the repairs. Anodized aluminum anchors replaced the stainless steel ones, and the top corner anchors were moved to the center of the top edge of each stone. The neoprene joints were removed and new colored siliconegaskets installed, and leveling screws rather than mortar used to keep the panels square. Work began in November 2011,[17] and originally was scheduled to end in 2014.[16] By February 2012, however, the contractor said work on the façade would end in late 2013, and site restoration would take place in 2014.[17] The East Building remained open throughout the project.[14]

In March 2013, the National Gallery of Art announced a $68.4 million renovation to the East Building. This included $38.4 million to refurbish the interior mechanical plant of the structure,[15] and $30 million to create new exhibition space.[14] Because the angular interior space of the East Building made it impossible to close off galleries,[15] the renovation required all but the atrium and offices to close by December 2013. The structure remained closed for three years. The architectural firm of Hartman-Cox oversaw both aspects of the renovation.[15]

A group of benefactors — which included Victoria and Roger Sant, Mitchell and Emily Rales, and David Rubenstein — privately financed the renovation. The Washington Post reported that the donation was one of the largest the NGA had received in a decade.[14] NGA staff said that they would use the closure to conserve artwork, plan purchases, and develop exhibitions. Plans for renovating conservation, construction, exhibition prep, groundskeeping, office, storage, and other internal facilities were also ready, but would not be implemented for many years.[15][18]

Buildings

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

-

North face of the West Building, with the west side of the East Building and the United States Capitol in background

-

Oculus of the West Building dome (2008)

-

Giacobbe Giusti, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

-

Moving walkway and light sculpture in concourse beneath 4th Street connecting East and West Buildings (2016)

Collection

Gerard van Honthorst‘s monumental masterwork, The Concert, was acquired by the NGA in 2013 and went on display for the first time in 218 years.

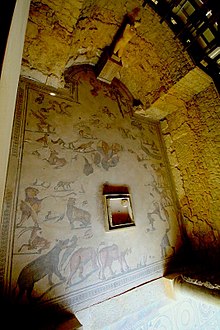

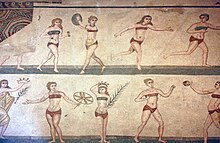

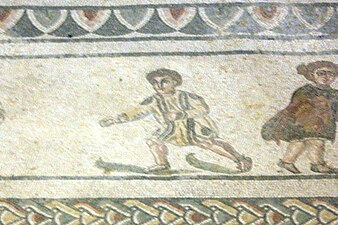

The NGA’s collection galleries and Sculpture Garden display European and American paintings, sculpture, works on paper, photographs, and decorative arts. The permanent collection of paintings extends from the Middle Ages to the present day. The Italian Renaissance collection includes two panels from Duccio‘s Maesta, the tondo of the Adoration of the Magi by Fra Angelico and Filippo Lippi, a Botticelli work on the same subject, Giorgione‘s Allendale Nativity, Giovanni Bellini‘s The Feast of the Gods, Ginevra de’ Benci (the only painting by Leonardo da Vinci in the Americas) and groups of works by Titian and Raphael.

Other European collections include examples of the work of many of the masters of western painting, including a version of Saint Martin and the Beggar, by El Greco, and works by Matthias Grünewald, Cranach the Elder, Rogier van der Weyden, Albrecht Dürer, Frans Hals, Rembrandt, Johannes Vermeer, Francisco Goya, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, and Eugène Delacroix, among others. The collection of sculpture and decorative arts includes such works as the Chalice of Abbot Suger of St-Denis and a collection of work by Auguste Rodin and Edgar Degas. Other highlights of the permanent collection include the second of the two original sets of Thomas Cole‘s series of paintings titled The Voyage of Life, (the first set is at the Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute in Utica, New York) and the original version of Watson and the Shark by John Singleton Copley(two other versions are in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and the Detroit Institute of Arts).

The National Gallery’s print collection comprises 75,000 prints, in addition to rare illustrated books. It includes collections of works by Albrecht Dürer, Rembrandt, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, William Blake, Mary Cassatt, Edvard Munch, Jasper Johns, and Robert Rauschenberg. The collection began with 400 prints donated by five collectors in 1941. In 1942, Joseph E. Widener donated his entire collection of nearly 2,000 works. In 1943, Lessing Rosenwald donated his collection of 8,000 old master and modern prints; between 1943 and 1979, he donated almost 14,000 more works. In 2008, Dave and Reba White Williams donated their collection of more than 5,200 American prints.[19]

In 2013, the NGA purchased from a private French collection Gerard van Honthorst‘s 1623 painting, The Concert, which had not been publicly viewed since 1795. After initially displaying the 1.23-by-2.06-metre (4.0 by 6.8 ft) The Concert in a special installation in the West Building, the NGA moved the painting to a permanent display in the museum’s Dutch and Flemish galleries.[20] Although the NGA did not reveal the amount that it had paid for The Concert, art experts estimated the sale price at $20 million.[21]

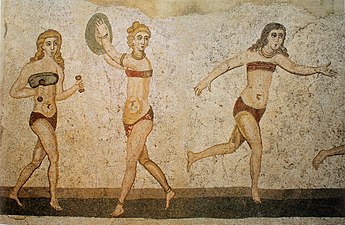

Highlights of the collection

Leonardo da Vinci, Ginevra de’ Benci, c. 1474

El Greco, Saint Martin and the Beggar, c. 1597-1599[22]

Peter Paul Rubens, Germanicus and Agrippina, 1614

Édouard Manet, The Railway, 1872

-

Rogier van der Weyden, Portrait of a Lady, c. 1460

-

Giorgione, Adoration of the Shepherds, c. 1500

-

Raphael, Cowper Madonna, 1504–5

-

Giovanni Bellini and Titian, The Feast of the Gods, c. 1514

-

Nicolas Poussin, The Assumption of the Virgin, c. 1626

-

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Mill, 1648

-

Johannes Vermeer, A Lady Writing a Letter, 1665-1666

-

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, A Young Girl Reading, c. 1776

-

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Marcotte d’Argenteuil, 1810

-

Eugène Delacroix, Columbus and His Son at La Rábida, 1838

-

Édouard Manet, The Old Musician, 1862

-

Édouard Manet, The Plum,1878

-

Claude Monet, The Artist’s Garden at Vétheuil, 1880

-

Vincent van Gogh, Self-portrait, August 1889

-

Paul Gauguin, Self-portrait,1889

-

Paul Cézanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat, 1888–1890

-

Vincent van Gogh, Woman in White, 1890

-

Claude Monet, Rouen Cathedral, West Facade, Sunlight, 1894

-

Henri Rousseau, The Equatorial Jungle, 1909

-

Francis Picabia, The Procession, Seville, 1912

-

Pablo Picasso, Still Life, 1918

Selected highlights from the American collection

Benjamin West, Portrait of Colonel Guy Johnson, 1775

George Bellows, New York, 1911

-

John Singleton Copley, Watson and the Shark,(original version), 1778

-

Gilbert Stuart, The Skater, 1782

-

Edward Savage, The Washington Family 1789-96

-

Edward Hicks, Peaceable Kingdom, c. 1834

-

Thomas Cole, The Voyage of Life: Childhood

-

Thomas Cole, The Voyage of Life: Youth

-

Thomas Cole, The Voyage of Life: Manhood

-

Thomas Cole, The Voyage of Life: Old Age

-

Thomas Cole, A View of the Mountain Pass Called the Notch of the White Mountains (Crawford Notch), 1839

-

Thomas Eakins, The Biglin Brothers Racing, 1873

-

Winslow Homer, Breezing Up (A Fair Wind), 1873–76

-

Frederic Edwin Church, Morning in The Tropics, (1877)

-

Mary Cassatt, The Loge,1882

-

Albert Pinkham Ryder, Siegfried and the Rhine Maidens, 1888-1891

-

Robert Henri, Snow in New York, 1902

-

George Bellows, Both Members of This Club 1909

-

Childe Hassam, Allies Day, May 1917, 1917

- List of most visited art museums

- Collections of the National Gallery of Art

- Micro Gallery, installed in 1995.

- Head of a Catalan Peasant and The Farm, both made by Joan Miró and preserved at the NGA.

- The Voyage of Life by Thomas Cole

Notes

- Jump up^ The Art Newspaper Review, April 2018

- Jump up^ Fink, Lois Marie “A History of the Smithsonian American Art Museum”, University of Massachusetts Press (2007) ISBN 978-1-55849-616-3, chapter 3

- Jump up^ National Gallery of Art website: general introduction ArchivedDecember 8, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- Jump up^ National Gallery of Art website: chronology Archived April 7, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- Jump up^ “National Gallery of Art, West Building”. American Architecture. Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 2 October2011.

- Jump up^ “National Gallery of Art”. Maps and Hours. 2016-01-12. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-01-03.

- Jump up^ NGA.gov Archived October 3, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- Jump up^ Leigh, Catesby (December 8, 2009). “An Ultramodern Building Shows Signs of Age”. The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on March 11, 2016.

- Jump up^ “In The Tower: Barnett Newman”. http://www.nga.gov. Archived from the original on 1 February 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- Jump up^ Menachem Wecker (August 1, 2012). “His Cross To Bear. Barnett Newman Dealt With Suffering in ‘Zips‘“. The Jewish Daily Forward. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013. Retrieved August 8,2012.

- Jump up^ “Leo Villareal: Multiverse”. http://www.nga.gov. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- Jump up^ “About the Gallery”. http://www.nga.gov. Archived from the original on 22 September 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- Jump up^ “Visit: Sculpture Garden”. http://www.nga.gov. Archived from the original on 26 September 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Boyle, Katherine and Parker, Lonnae O’Neal. “National Gallery of Art Announces $30 Million Renovation to East Building.” Washington Post. March 12, 2013. Archived April 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 2013-03-13.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Boyle, Katherine. “National Gallery Sees Long-Term Benefit in Long Closing of East Building.” Washington Post. March 13, 2013.Archived January 6, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 2013-03-22.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Kelly, John. “Why National Gallery’s East Building Shed Its Pink Marble Skin.” Washington Post. February 21, 2012. ArchivedJanuary 6, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 2013-03-13.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Dietsch, Deborah K. “National Gallery of Art’s Famed East Building Gets a Facelift.” Washington Business Journal. February 3, 2012. Archived October 18, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 2013-03-13.

- Jump up^ “The CIVITAS Chronicles”. traditional-building.com. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-03-23.

- Jump up^ “Prints”. Nga.gov. 2013-06-19. Archived from the original on 2013-12-21. Retrieved 2013-12-22.

- Jump up^ Boyle, Katherine. “National Gallery Acquires ‘The Concert’ by Dutch Golden Age Painter Honthorst.” Washington Post. November 22, 2013. Archived August 29, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 2013-11-22.

- Jump up^ Vogel, Carol. “National Gallery Acquires a van Honthorst Masterwork.” New York Times. November 21, 2013. ArchivedFebruary 24, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 2013-11-22.

- Jump up^ “Provenance”. Nga.gov. Archived from the original on 2009-05-07. Retrieved 2013-12-22.

Further reading

- David Cannadine, Mellon: An American Life, Knopf, 2006, ISBN 0-679-45032-7

- Neil Harris, Capital Culture: J. Carter Brown, the National Gallery of Art, and the Reinvention of the Museum Experience, University of Chicago Press, 2013, ISBN 9780226067704

- Andrew Kelly, Kentucky by Design: The Decorative Arts, American Culture, and the Index of American Design, University Press of Kentucky, 2015. ISBN 978-0-8131-5567-8

- “The National Gallery of Art, Washington”, special number of Connaissance des Arts, Société Français de Promotion Artistique (2000) ISSN 1242-9198

| National Gallery of Art. |