Giacobbe Giusti, Collegiate Church of the Assumption of Mary, San Gimignano

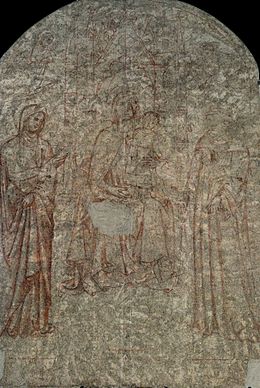

Pharaoh and his soldiers are drowned crossing the Red Sea, from the Old Testament cycle by Bartolo di Fredi

Giacobbe Giusti, Collegiate Church of the Assumption of Mary, San Gimignano

The Creation of Adam by Bartolo di Fred

Giacobbe Giusti, Collegiate Church of the Assumption of Mary, San Gimignano

Giacobbe Giusti, Collegiate Church of the Assumption of Mary, San Gimignano

Giacobbe Giusti, Collegiate Church of the Assumption of Mary, San Gimignano

The Last Supper all from the New Testament cycle by Lippo Memmi

Giacobbe Giusti, Collegiate Church of the Assumption of Mary, San Gimignano

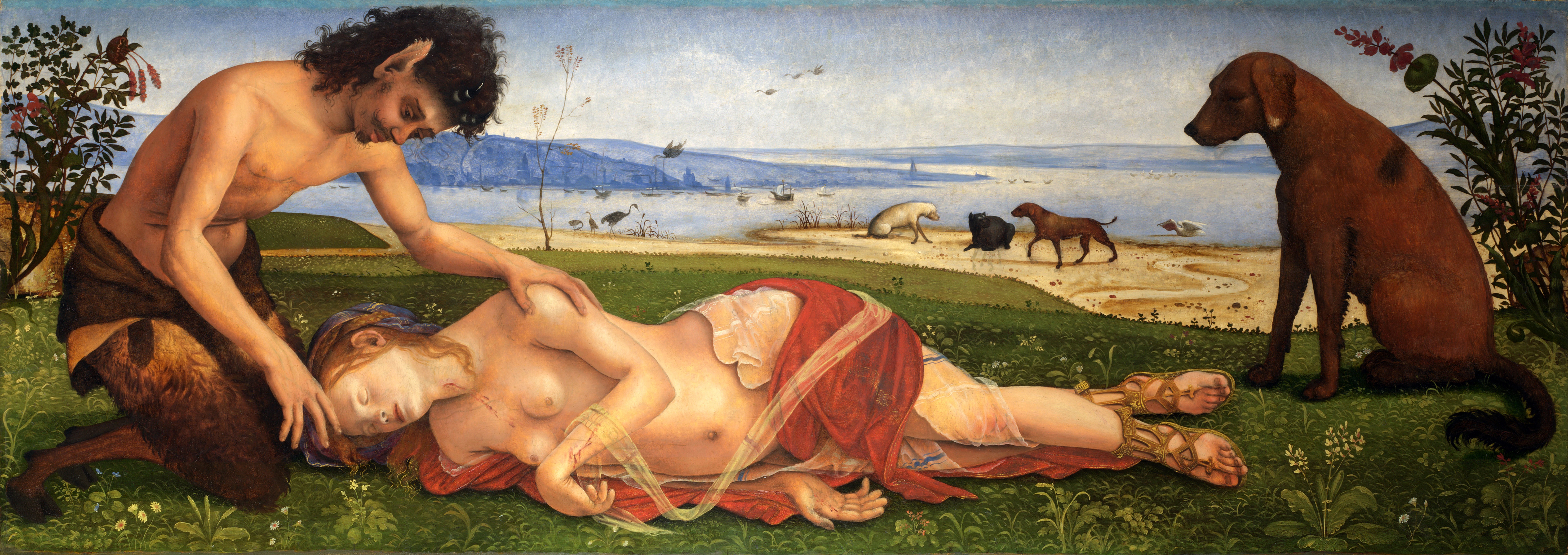

The Funeral of Santa Fina Domenico Ghirlandaio

Giacobbe Giusti, Collegiate Church of the Assumption of Mary, San Gimignano

Giacobbe Giusti, Collegiate Church of the Assumption of Mary, San Gimignano

The Collegiate Church of Santa Maria Assunta, San Gimignano is a Roman Catholic collegiate churchand minor basilica[1] located in San Gimignano, Tuscany, central Italy, situated in the Piazza del Duomo at the town’s heart. The church is famous for its fresco cycles which include works by Domenico Ghirlandaio, Benozzo Gozzoli, Taddeo di Bartolo, Lippo Memmi and Bartolo di Fredi. The basilica is located within the UNESCO World Heritage Site of the “Historic Centre of San Gimignano”, with its frescos being described by UNESCO as “works of outstanding beauty”.[2]

History

The first church on the site was begun in the 10th century.[3] During the early 12th century the importance of San Gimignano, and its principal church, grew steadily, owing to the town’s location on the pilgrimage route to Rome, the Via Francigena.[citation needed] The present church on this site was consecrated on 21 November 1148 and dedicated to St. Geminianus (San Gimignano) in the presence of Pope Eugenius III and 14 prelates.[3] The event is commemorated in a plaque on the facade.[3] The power and authority of the city of San Gimignano continued to grow, until it was able to win autonomy from Volterra. The church owned land and enjoyed numerous privileges that were endorsed by papal bulls and decrees.[4] It was elevated to collegiate status 20 September 1471.[5]

During the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries, the church was enriched by the addition of frescos and sculpture.[4] The western end of the building (liturgical east) was altered and extended by Giuliano da Maiano between 1466 and 1468, with the work including vestries, the Chapel of Conception and the Chapel of St Fina.[3] The church was damaged during World War II, and during the subsequent restoration in 1951 the triapsidal eastern end of the earlier church was discovered lying beneath the nave of the present church.[3]

The church possesses the relics of St. Geminianus, the beatified Bishop of Modena and patron saint of the town, whose feast day is celebrated on 31 January. On 8 May 1300 Dante Alighieri came to San Gimignano as the Ambassador of the Guelph League in Tuscany.[6]Girolamo Savonarola preached from the pulpit of this church in 1497.[4]

Architecture

Interior, Collegiate Church

The Collegiate Church stands on the west side of Piazza del Duomo, so named although the church has never been the seat of a bishop.[7] The church has an east-facing facade, and chancel to the west, as at St Peter’s Basilica. The architecture is 12th and 13th century Romanesquewith the exception of the two chapels in the Renaissance style. The facade, which has little ornament, is approached from the square by a wide staircase and has a door into each of the side aisles, but no central portal. The doorways are surmounted by stone lintels with recessed arches above them, unusual in incorporating the stone Gabbro.[8] There is a central ocular window at the end of the nave and a smaller one giving light to each aisle. The facade, which is stone, was raised higher in brick in 1340, when the ribbed vaulting was constructed, and the two smaller ocular windows set in.[7] Matteo di Brunisend is generally credited as the main architect of the medieval period, with his date of activity given as 1239, but in fact his contribution may have been little more than the design of the central ocular window.[8] Beneath this window is a slot which marks the place of a window which lit the chancel of the earlier church, and may be the most visible sign of the church’s reorientation in the 12th century rebuilding, although this is not entirely agreed upon by scholars.[8]

To the north side of the church, in the corner of the transept and chancel, stands a severely plain campanile of square plan, with a single arched opening in each face. The campanile may be that of the earlier church, as it appears to mark the extent of the original western facade, or it may have been one of the city’s many tower houses, pressed into service of the church. To the south side of the church is the Loggia of the Baptistry, a 14th-century arcaded cloister with stout octagonal columns and a groin vault.[9]

Internally, the building is in the shape of a Latin Cross, with central nave and an aisle on either side, divided by arcades of seven semi-circular Romanesque arches resting on columns with simplified Corinthianesque capitals.[10] The chancel is a simple rectangle with a single arched window at the terminal end. The roofs throughout are of quadripartite vaults which date from the mid 14th century.[7] Although Gothic by date and decoration, the profiles of the ribs are semi-circular in the Romanesque manner. The clerestory has small windows, inserted when the nave was vaulted, along with lancet windows in the north aisle, the aisle windows were subsequently blocked for the painting of the fresco cycle, making the interior very dark.[10]

Decoration

The Romanesque architectural details of the church’s interior are emphasised by the decorative use of colour, with the voussoirs of the nave arcades being of alternately black and white marble, creating stripes, as seen at Orvieto Cathedral. The vault compartments are all painted with lapis lazuli dotted with gold stars, and the vaulting ribs are emphasised with bands of geometric decoration predominantly in red, white and gold.

The church is most famous for its largely intact scheme of frescodecoration, the greater part of which dates from the 14th century, and represents the work of painters of the Sienese school, influenced by the Byzantine traditions of Duccio and the Early Renaissancedevelopments of Giotto. The frescoes comprise a Poor Man’s Bible of Old Testament cycle, New Testament cycle, and Last Judgement, as well as an Annunciation, a Saint Sebastian, and the stories of a local saint, St Fina, as well as several smaller works.

Old Testament cycle

The Creation of Adam by Bartolo di Fredi

The wall of the left aisle had six decorated bays, of which the paintings of the first bay are in poor condition and those of the sixth have been damaged and in part destroyed by the insertion of the pipe organ. The remaining paintings, with the exception of a repainted panel in the sixth bay, are the work of Bartolo di Fredi, and, according to an inscription, were completed around 1356.[11] The paintings are in three registers and proceed from left to right chronologically in each register.[11]

Upper level

The upper register occupies the lunettes beneath the vault and depicts the story of Creation.[11]

- Creation of the Firmament

- Creation of Man

- Adam names the animals

- Creation of Eve

- God commands Adam and Eve not to touch the forbidden fruit

- The Original Sin (lost)[11]

Middle level

Pharaoh and his soldiers are drowned crossing the Red Sea, from the Old Testament cycle by Bartolo di Fredi

The second register has ten remaining scenes, with two at the furthest right having been lost with the insertion of the organ.[11]

- The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden (very incomplete)

- Cain kills Abel (very incomplete)

- Noah and his family building the Ark

- Animals entering the Ark

- Noah and his family giving thanks after the Great Flood

- The Drunkenness of Noah

- The departure of Abraham and Lot from the land of the Chaldeans

- Abraham and Lot go separate ways.

- Joseph‘s dream

- Joseph is put into a well by his brothers

- Story of Joseph in Egypt (lost)

- Story of Joseph in Egypt (lost) [11]

Lower level

Giacobbe Giusti, Collegiate Church of the Assumption of Mary, San Gimignano

Two scenes from the story of Job. The Devil bargains with God over Job’s faith.

The Devil has the men and herds of Job slaughtered. Bartolo di Fredi

In the lower register, there are ten scenes.[11]

- Joseph, has his brothers arrested (very incomplete)

- Joseph makes his identity known to his family (incomplete)

- Moses changes the rod into a serpent

- The army of Pharaoh are drowned in the Red Sea. (this scene occupies two sections)

- Moses on Mount Sinai

- The devil is sent to Job by God

- The men and herds of Job are killed

- The house of Job falls, killing his sons.

- Job prays to God

- Job, plagued by boils, is visited by friends. (incomplete)

- (Lost scene)[11]

New Testament cycle

The six decorated bays of the right aisle, with scenes of the New Testament, pose a problem of authorship. Giorgio Vasari states that they are the work of “Barna of Siena” and relates that Barna fell to his death from the scaffolding.[12] The name “Barna” in relation to paintings at the Collegiate Church of San Gimignano appears to have originated in Lorenzo Ghiberti‘s Commentaries. In 1927 the archivist Peleo Bacci made the suggestion that Barna had never existed and that the paintings are the work of Lippo Memmi. This hypothesis received no support and little comment for fifty years.[13] In 1976 discussion of Bacci’s attribution was revived, with Moran suggesting that there had been a mis-transcription of “Bartolo” as “Barna”, with the name “Bartolo” referring to Bartolo di Fredi, painter of the Old Testament cycle.[14]

The attribution of the New Testament cycle to Lippo Memmi, perhaps assisted by his brother Federico Memmi and father Memmo di Filippucci, is now generally agreed.[13] Lippo Memmi was influenced by his more famous brother-in-law, Simone Martini.[7] Lippo Memmi also painted a large Maesta in the Town Hall of San Gimignano, in imitation of that done by Simone Martini at the Town Hall of Siena. The New Testament cycle of the right aisle appears to pre-date the Old Testament cycle and is generally accepted to date from c.1335-1345.[15]

The scenes within the New Testament cycle are organised into four separate narratives, and do not follow a clear left-to-right pattern as do those of the left aisle. As with the left aisle, they are divided into three registers, the upper being the lunettes between the vaults.[15]

Upper level

The upper register shows the Birth of Christ. The series reads from right to left, in six bays.[15]

- The Annunciation

- The Nativity and adoration of the shepherds

- The adoration of the Magi

- The Presentation at the Temple

- The Massacre of the Innocents

- The Flight into Egypt[15]

Middle level

Giacobbe Giusti, Collegiate Church of the Assumption of Mary, San Gimignano

Jesus enters Jerusalem on a donkey

Jesus calls Lazarus forth from the tomb

The middle register shows scenes of the Life of Christ, beginning at the 4th bay, below the picture of the Presentation at the Temple, and reading left to right, with eight scenes.[15] The scenes have been skilfully juxtaposed so that narrative elements may be compared or contrasted. Within the fourth bay is shown the Presentation of the Temple, Jesus sitting among the Doctors of the Temple of Jerusalem as a twelve-year-old, and Jesus before his crucifixion, enthroned, crowned with thorns and mocked.[15]

- Jesus among the Doctors of the Temple of Jerusalem

- The Baptism of Jesus

- The Calling of Peter

- The Wedding at Cana of Galilee (damaged in WWII)

- The Transfiguration

- The Resurrection of Lazarus

- Jesus enters Jerusalem

- The people welcome Jesus to Jerusalem (the final two scenes are a single event spread over two frames)[15]

Lower level

Giacobbe Giusti, Collegiate Church of the Assumption of Mary, San Gimignano

Judas receives thirty pieces of silver to betray Jesus

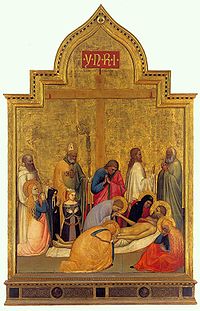

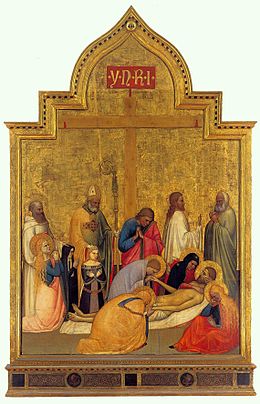

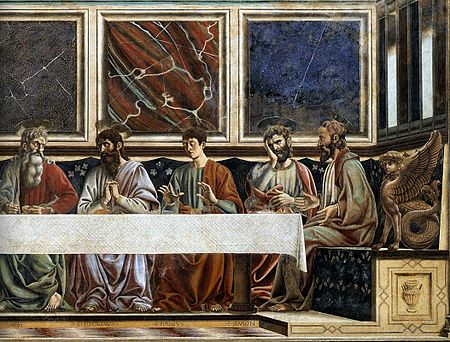

The Last Supper all from the New Testament cycle by Lippo Memmi

The lower register, showing the Passion of Christ, continues beneath the Entry into Jerusalem, and is read from right to left in eight scenes over four bays.[15]

- The Last Supper

- Judas agrees to betray Jesus for thirty pieces of silver

- Jesus prays in the Garden of Gethsemane

- The Kiss of Judas

- Jesus at the Praetorium

- The Scourging of Jesus

- Jesus crowned with thorns and mocked

- Jesus carrying the cross to Calvary [15]

Bays five and six

Bay five, beneath the lunette of the Slaughter of the Innocents, has a single large scene of the Crucifixion.[15]

Bay six, beneath the lunette of the Flight into Egypt contained four scenes (destroyed in the 15th century) of post-crucifixion events[15]which are thought to have been:

- The Deposition

- The Descent into Limbo

- The Resurrection

- Pentecost

The Last Judgement

This scene is painted in fresco on the inner wall of the facade and the adjoining walls of the nave. The work was completed in 1393 by Taddeo di Bartolo, one of the foremost Sienese painters of the 14th century. The central section shows the figure of Christ as Judge, accompanied by the Virgin Mary and St John, with the Apostles. On the right wall is the image of Paradise, in a ruined state. On the left side Hell is represented, along with various depictions of the gruesome torments to be suffered by those who commit and of the Seven Deadly Sins.[16]

Chapel of Santa Fina

Giacobbe Giusti, Collegiate Church of the Assumption of Mary, San Gimignano

Pope Gregory announces the death of Santa Fina

The Funeral of Santa Fina Domenico Ghirlandaio

This chapel off the right aisle, which has been described as “one of the jewels of Renaissance architecture, painting and sculpture”, is dedicated to a young girl, Serafina, known as “Fina” and regarded locally as a saint.[10] Fina, a child renowned for her piety, was orphaned at an early age, and then suffered a disease which rendered her invalid. She lay each day on a wooden palette, and was nursed by two women.[17] According to her legend, eight days before her death at the age of fifteen, Fina had a vision of Pope Gregory who told her that death was near.[17] On the day of her death, 12 March 1253, the bells of San Gimignano rang spontaneously, and large pale mauve flowers grew around her palette. As her nurse laid out her body, her hand moved, touching the nurse and healing her of paralysis that she had suffered as the result of many hours of supporting Fina’s head. On the day of her funeral, a blind choir boy had his sight restored by touching her feet. It is said that mauve flowers bloom in San Gimignano every year on the anniversary of her death.[17]

A chapel dedicated to St Fina was built off the right aisle by Giuliano da Maiano, and has architectural details and a finely carved altarpiece by Benedetto da Maiano.[10] The side walls of the chapel were painted in fresco by Domenico Ghirlandaio around 1475, showing, on the walls, Santa Fina’s visitation by Pope Gregory and Santa Fina’s Funeral, with the various miracles including the two healings and an angel rings the bells in the background. The vault and spandrels were decorated by Sebastiano Mainardi and have figures of Evangelists, Prophets and Doctors of the Church.[17]

Chapel of the Conception

The chapel was built in 1477 and modified in the 17th century. The side lunettes have frescoes by Niccolo di Lapi representing the Birth of the Virgin and St Philip Neri celebration mass. The vault shows the Coronation of the Virgin painted by Pietro Dandini. The altarpiece is the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception by Ludovico Cardi, late 16th century.[18]

Other artworks

Giacobbe Giusti, Collegiate Church of the Assumption of Mary, San Gimignano

The Martyrdom of St Sebastian by Benozzo Gozzoli (1465) honours the saint who was invoked in times of plague.

St Sebastian

On the rear wall of the nave, beneath the Last Judgement is a fresco of the Martyrdom of St Sebastian painted by Benozzo Gozzoli in 1465. The work was commissioned by the people of San Gimignano as the result of a vow that they made to honour the saint, whose intervention was believed to have brought relief from an outbreak of plague in 1464. The painting shows the figure of Christ and the Virgin Mary in Glory, while below, St Sebastian, standing on a Classical plinth and bristling with arrows, suffers martyrdom and is crowned by angels.[19]

Benozzo Gozzoli received his training under Lorenzo Ghiberti while working on the Baptistry doors.[19] He fulfilled two other important commissions in San Gimignano. Both were at the Church of Sant’ Agostino, a fresco cycle of the life of St Augustine of Hippo executed 1464-65, and another St Sebastian, showing the townsfolk sheltering beneath his cloak.[20]

The Annunciation

Giacobbe Giusti, Collegiate Church of the Assumption of Mary, San Gimignano

The Annunciation, by Sebastiano Mainardi is located in the Baptistry Loggia beside the church.

In the Baptistery Loggia to the south of the church are several small frescoes of saints, and a major work, The Annunciation, previously attributed to Ghirlandaio but now believed to be the work of Sebastiano Mainardi and dated to 1482.[9] In front of The Annunciation stands the font, which was removed from the church and placed in this position in 1632. It is hexagonal, with a sculptured relief on the side, that to the front being the Baptism of Christ, with the two adjoining panels containing kneeling angels. It is the work of the Sienese sculptor Giovanni di Cecco and was commissioned by the Wool-workers Guild in 1379.[9]

Works by Jacopo della Quercia and others

- The Annunciate angel and the Virgin Mary, two figures carved in wood by Jacopo della Quercia stand towards the end of the nave. They were created around 1421 and later decorated with polychrome by Martino di Martolomeo.[19]

- Pope Gregory predicts the death of St Fina, an early 14th-century fresco in a lunette of the right nave arcade, thought to be the work of Nicolo di Segna di Bonaventura.[17]

- The main altar of the church has a large marble ciborium and two kneeling angels with candlesticks, the work of Benedetto Maiano, created at the same time as the altarpiece and tabernacle in the Chapel of Santa Fina, 1475.[21]

- The crucifix of the chancel is by the Florentine sculptor, Giovanni Antonio Noferi, 1754. Noferi also designed the marble pavement of the chancel.[21]

Further reading

- Schiapparelli, Luigi (1913). Le carte del monastero di S.Maria in Firenze (Badia). Rome: Loescher.

- Salmi, Mario (1927). Architettura romanica in Toscana. Milan-Rome: Bestetti&Tumminelli.

- Franz Hofmann Der Freskenzyklus des Neuen Testaments in der Collegiata von San Gimignano München 1996 ISBN 3-89235-065-5

References

- Jump up^ “Basilica S. Maria Assunta”. GCatholic.org. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- Jump up^ UNESCO: Historic Centre of San Gimignano, (accessed 05-09-2012)

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Anonymous (1996), p. 86

- ^ Jump up to:a b c San Gimignano (accessed 02-09-2012)

- Jump up^ Emanuele Repetti, Gazetteer, physicist, historian of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, Florence, 1833-1846.

- Jump up^ Cummune di San Gimignano, (accessed 02-09-2012)

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d von der Haegen & Strasser (2001), pp. 438–441

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Anonymous (1996), p. 88

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Vantaggi (1979), p. 53

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Vantaggi (1979), p. 16

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h Vantaggi (1979), pp. 19–29

- Jump up^ Giorgio Vasari, Le Vite delle più eccellenti pittori, scultori, ed architettori, Part I, “Barna of Siena“, (accessed 11-09-2012)

- ^ Jump up to:a b Moran (1998), pp. 79–81

- Jump up^ Gordon Moran, Is the name Barna an incorrect transcription of the name Bartolo, Sansoni, Florence (1976)

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k Vantaggi (1979), pp. 34–40

- Jump up^ Vantaggi (1979), pp. 30–32

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Vantaggi (1979), pp. 41–49

- Jump up^ Vantaggi (1979), p. 28

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Vantaggi (1979), p. 33

- Jump up^ Diane Cole Ahl, Benozzo Gozzoli’s Frescoes of the Life of Saint Augustine in San Gimignano: Their Meaning in Context, Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 7, No. 13 (1986), pp. 35-53

- ^ Jump up to:a b Vantaggi (1979), p. 51

Bibliography

- Anonymous (1996). Chiese medievali della Valdelsa. I territori della via Francigena tra Siena e S. Gimignano [Medieval Churches of the Val d’Elsa. The territories of the Via Francigena between Siena and San Gimignano, Empoli] (in Italian). dell’Acero. ISBN 88-86975-08-2.

- von der Haegen, Anne Mueller; Strasser, Ruth (2001). Art & Architecture: Tuscany. Könemann. ISBN 978-3-8290-2652-9.

- Moran, Gordon (1998). Silencing Scientists and Scholars in Other Fields. Ablex. ISBN 1-56750-343-8.

- Vantaggi, Rosella (1979). San Gimignano: Town of the Fine Towers. Plurigraf.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collegiate_Church_of_San_Gimignano

http://www.giacobbegiusti.com