Giacobbe Giusti, “Garden of Eden” mosaic in mausoleum of Galla Placidia. UNESCO World heritage site. Ravenna, Italy. 5th century A.D.

Giacobbe Giusti, “Garden of Eden” mosaic in mausoleum of Galla Placidia. UNESCO World heritage site. Ravenna, Italy. 5th century A.D.

Fifth century “Garden of Eden” mosaic in mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna, Italy. UNESCO World heritage site.

Giacobbe Giusti, “Garden of Eden”

The Garden of Eden as depicted in the first or left panel of Bosch‘s The Garden of Earthly Delights triptych. The panel includes many imagined and exotic Africananimals.[1]

The Garden of Eden (Hebrew גַּן עֵדֶן, Gan ʿEḏen), also called Paradise, is the biblical “garden of God” described in the Book of Genesis and the Book of Ezekiel.[2][3] Genesis 13:10 refers to the “garden of God”,[4] and the “trees of the garden” are mentioned in Ezekiel 31.[5] The Book of Zechariahand the Book of Psalms also refer to trees and water without explicitly mentioning Eden.[6]

The name derives from the Akkadianedinnu, from a Sumerian word edinmeaning “plain” or “steppe”, closely related to an Aramaic root word meaning “fruitful, well-watered”.[3]Another interpretation associates the name with a Hebrew word for “pleasure”; thus the Douay-Rheims Bible in Genesis 2:8 has the wording “And the Lord God had planted a paradise of pleasure” rather than “a garden in Eden”. The Hebrew term is translated “pleasure” in Sarah’s secret saying in Genesis 18:12.[7]

Like the Genesis flood narrative, the Genesis creation narrative and the account of the Tower of Babel, the story of Eden echoes the Mesopotamian myth of a king, as a primordial man, who is placed in a divine garden to guard the Tree of Life.[8] The Hebrew Bible depicts Adam and Eve as walking around the Garden of Eden naked due to their innocence.[9]

The location of Eden is described in the Book of Genesis as the source of four tributaries. The Garden of Eden is considered to be mythological by most scholars.[10][11][12][13] Among those that consider it to have been real, there have been various suggestions for its location:[14] at the head of the Persian Gulf, in southern Mesopotamia (now Iraq) where the Tigris and Euphrates rivers run into the sea;[15]and in Armenia.[16][17][18]

Biblical narratives

Giacobbe Giusti, “Garden of Eden”

Expulsion from Paradise, painting by James Jacques Joseph Tissot

The Expulsion illustrated in the English Caedmon manuscript, c. 1000 CE

Genesis

The second part of the Genesis creation narrative, Genesis 2:4-3:24, opens with YHWH–Elohim(translated here “the LORDGod”, see Names of God in Judaism) creating the first man (Adam), whom he placed in a garden that he planted “eastward in Eden”.[19] “And out of the ground made the Lord God to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight, and good for food; the tree of life also in the midst of the garden, and the tree of knowledge of good and evil.”[20]

The man was free to eat from any tree in the garden except the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Last of all, the God made a woman (Eve) from a rib of the man to be a companion for the man. In chapter three, the man and the woman were seduced by the serpent into eating the forbidden fruit, and they were expelled from the garden to prevent them from eating of the tree of life, and thus living forever. Cherubim were placed east of the garden, “and a flaming sword which turned every way, to guard the way of the tree of life” (Genesis 3:24).

Genesis 2:10–14 lists four rivers in association with the garden of Eden: Pishon, Gihon, Chidekel (the Tigris), and Phirat (the Euphrates). It also refers to the land of Cush—translated/interpreted as Ethiopia, but thought by some to equate to Cossaea, a Greek name for the land of the Kassites.[21] These lands lie north of Elam, immediately to the east of ancient Babylon, which, unlike Ethiopia, does lie within the region being described.[22] In Antiquities of the Jews, the first-century Jewish historian Josephus identifies the Pishon as what “the Greeks called Ganges” and the Geon (Gehon) as the Nile.[23]

According to Lars-Ivar Ringbom the paradisus terrestris is located in Shiz in northeastern Iran.[24]

Ezekiel

In Ezekiel 28:12–19 the prophet Ezekiel the “son of man” sets down God’s word against the king of Tyre: the king was the “seal of perfection”, adorned with precious stones from the day of his creation, placed by God in the garden of Eden on the holy mountain as a guardian cherub. But the king sinned through wickedness and violence, and so he was driven out of the garden and thrown to the earth, where now he is consumed by God’s fire: “All those who knew you in the nations are appalled at you, you have come to a horrible end and will be no more.” (v.19).

According to Terje Stordalen, the Eden in Ezekiel appears to be located in Lebanon.[25] “[I]t appears that the Lebanon is an alternative placement in Phoenician myth (as in Ez 28,13, III.48) of the Garden of Eden”,[26] and there are connections between paradise, the garden of Eden and the forests of Lebanon (possibly used symbolically) within prophetic writings.[27] Edward Lipinski and Peter Kyle McCarter have suggested that the Garden of the gods (Sumerian paradise), the oldest Sumerian version of the Garden of Eden, relates to a mountain sanctuary in the Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon ranges.[28]

Proposed locations

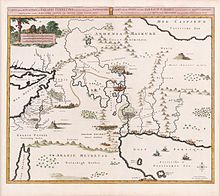

Map by Pierre Mortier, 1700, based on theories of Pierre Daniel Huet, Bishop of Avranches. A caption in French and Dutch reads: Map of the location of the terrestrial paradise, and of the country inhabited by the patriarchs, laid out for the good understanding of sacred history, by M. Pierre Daniel Huet.

The Garden of Eden is considered to be mythological by most scholars.[10][11][12][29][13][30]However there have been suggestions for its location:[14]for example, at the head of the Persian Gulf, in southern Mesopotamia (now Iraq) where the Tigris and Euphrates rivers run into the sea;[15] and in the Armenian Highlands or Armenian Plateau.[16][31][17][18] British archaeologist David Rohl locates it in Iran, and in the vicinity of Tabriz, but this suggestion has not caught on with scholarly sources.[32]

The location of Eden is described in the Book of Genesis, chapter 2, verses 10–14:

And a river departed from Eden to water the garden, and from there it divided and became four tributaries.

The name of the first is Pishon, which is the circumnavigator of the land of Havilah where there is gold. And the gold of this land is good; there are bdellium and cornelian stone. And the name of the second river is Gihon, which is the circumnavigator of the land of Cush. And the name of the third is Chidekel, which is that which goes to the east of Ashur; and the fourth river is Phirat.

Parallel concepts

- Dilmun in the Sumerian story of Enki and Ninhursag is a paradisaical abode[33] of the immortals, where sickness and death were unknown.[34]

- The garden of the Hesperides in Greek mythology was somewhat similar to the Christian concept of the Garden of Eden, and by the 16th century a larger intellectual association was made in the Cranach painting (see illustration at top). In this painting, only the action that takes place there identifies the setting as distinct from the Garden of the Hesperides, with its golden fruit.

- The Persian term “paradise” (borrowed as Hebrew: פרדס, pardes), meaning a royal garden or hunting-park, gradually became a synonym for Eden after c. 500 BCE. The word “pardes” occurs three times in the Hebrew Bible, but always in contexts other than a connection with Eden: in the Song of Solomon iv. 13: “Thy plants are an orchard (pardes) of pomegranates, with pleasant fruits; camphire, with spikenard”; Ecclesiastes 2. 5: “I made me gardens and orchards (pardes), and I planted trees in them of all kind of fruits”; and in Nehemiah ii. 8: “And a letter unto Asaph the keeper of the king’s orchard (pardes), that he may give me timber to make beams for the gates of the palace which appertained to the house, and for the wall of the city.” In these examples pardes clearly means “orchard” or “park”, but in the apocalyptic literature and in the Talmud “paradise” gains its associations with the Garden of Eden and its heavenly prototype, and in the New Testament“paradise” becomes the realm of the blessed (as opposed to the realm of the cursed) among those who have already died, with literary Hellenistic influences.

Jewish eschatology

In the Talmud and the Jewish Kabbalah,[35] the scholars agree that there are two types of spiritual places called “Garden in Eden”. The first is rather terrestrial, of abundant fertility and luxuriant vegetation, known as the “lower Gan Eden”. The second is envisioned as being celestial, the habitation of righteous, Jewish and non-Jewish, immortal souls, known as the “higher Gan Eden”. The Rabbanim differentiate between Gan and Eden. Adam is said to have dwelt only in the Gan, whereas Eden is said never to be witnessed by any mortal eye.[35]

According to Jewish eschatology,[36][37] the higher Gan Eden is called the “Garden of Righteousness”. It has been created since the beginning of the world, and will appear gloriously at the end of time. The righteous dwelling there will enjoy the sight of the heavenly chayotcarrying the throne of God. Each of the righteous will walk with God, who will lead them in a dance. Its Jewish and non-Jewish inhabitants are “clothed with garments of light and eternal life, and eat of the tree of life” (Enoch 58,3) near to God and His anointed ones.[37] This Jewish rabbinical concept of a higher Gan Eden is opposed by the Hebrew terms gehinnom[38] and sheol, figurative names for the place of spiritual purification for the wicked dead in Judaism, a place envisioned as being at the greatest possible distance from heaven.[39]

In modern Jewish eschatology it is believed that history will complete itself and the ultimate destination will be when all mankind returns to the Garden of Eden.[40]

Islamic view

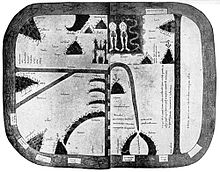

Mozarabic world map from 1109 with Eden in the East (at top)

The term jannāt ʿadni(“Gardens of Eden” or “Gardens of Perpetual Residence”) is used in the Qur’an for the destination of the righteous. There are several mentions of “the Garden” in the Qur’an (2:35, 7:19, 20:117), while the Garden of Eden, without the word ʿadn,[41] is commonly the fourth layer of the Islamic heaven and not necessarily thought as the dwelling place of Adam.[42] The Quran refers frequently over various Surah about the first abode of Adam and his wife, including surat Sad, which features 18 verses on the subject (38:71–88), surat al-Baqara, surat al-A’raf, and surat al-Hijr although sometimes without mentioning the location. The narrative mainly surrounds the resulting expulsion of Adam and Eve after they were tempted by Shaitan. Despite the Biblical account, the Quran mentions only one tree in Eden, the tree of immortality, which God specifically claimed it was forbidden to Adam and Eve. Some exegesis added an account, about Satan, disguised as a serpent to enter the Garden, repeatedly told Adam to eat from the tree, and eventually both Adam and Eve did so, resulting in disobeying God.[43] These stories are also featured in the hadith collections, including al-Tabari.[44]

Latter-day Saints

Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (also known as Mormons or Latter-day Saints) believe that after Adam and Eve were expelled from the Garden of Eden they resided in a place known as Adam-ondi-Ahman, located in present-day Daviess County, Missouri. It is recorded in the Doctrine and Covenants that Adam blessed his posterity there and that he will return to that place at the time of the final judgement[45][46] in fulfillment of biblical prophecy.[47]

Numerous early leaders of the Church, including Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, and George Q. Cannon, taught that the Garden of Eden itself was located in nearby Jackson County, Missouri,[48] but there are no surviving first-hand accounts of that doctrine being taught by Joseph Smith himself. LDS doctrine is unclear as to the exact location of the Garden of Eden, but tradition among Latter-Day Saints places it somewhere in the vicinity of Adam-ondi-Ahman, or in Jackson County.[49][50]

Art

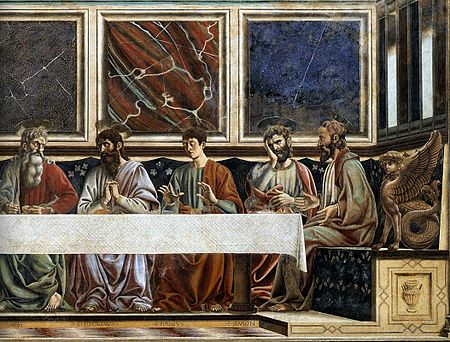

The Garden of Eden motifs most frequently portrayed in illuminated manuscripts and paintings are the “Sleep of Adam” (“Creation of Eve”), the “Temptation of Eve” by the Serpent, the “Fall of Man” where Adam takes the fruit, and the “Expulsion”. The idyll of “Naming Day in Eden” was less often depicted. Much of Milton’s Paradise Lost occurs in the Garden of Eden. Michelangelo depicted a scene at the Garden of Eden in the Sistine Chapel ceiling. In the Divine Comedy, Danteplaces the Garden at the top of Mt. Purgatory. For many medieval writers, the image of the Garden of Eden also creates a location for human love and sexuality, often associated with the classic and medieval trope of the locus amoenus.[51] One of oldest depictions of Garden of Eden is made in Byzantine style in Ravenna, while the city was still under Byzantine control. A preserved blue mosaic is part of the mausoleum of Galla Placidia. Circular motifs represent flowers of the garden of Eden.

-

The Garden of Eden by Lucas Cranach der Ältere, a 16th-century German depiction of Eden

-

The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man by Jan Brueghel the Elder and Pieter Paul Rubens, depicting both domestic and exotic wild animals such as tigers, parrots and ostriches co-existing in the garden

-

Fifth century “Garden of Eden” mosaic in mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna, Italy. UNESCO World heritage site.

-

“The Garden of Eden” by Thomas Cole (c. 1828)

-

“The Garden of Eden” by Adi Holzermade in 2012.