Giacobbe Giusti, Hadrian’s Villa

Giacobbe Giusti, Hadrian’s Villa

Giacobbe Giusti, Hadrian’s Villa

Giacobbe Giusti, Hadrian’s Villa

Giacobbe Giusti, Hadrian’s Villa

Giacobbe Giusti, Hadrian’s Villa

|

|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| Location | Tivoli, Italy |

| Coordinates | 41°56′31″N 12°46′31″E |

| Criteria | Cultural: (i), (ii), (iii) |

| Reference | 907 |

| Inscription | 1999 (23rd Session) |

Hadrian’s Villa (Villa Adriana in Italian) is a large Roman archaeological complex at Tivoli, Italy. It is the property of the Republic of Italy, and has been directed and run by the Polo Museale del Lazio since December 2014.

ContentsHistory

The villa was constructed at Tibur (modern-day Tivoli) as a retreat from Rome for Roman Emperor Hadrian during the second and third decades of the 2nd century AD. Hadrian is said to have disliked the palace on the Palatine Hill in Rome, leading to the construction of the retreat. It was traditional that the Roman emperor had constructed a villa as a place to relax from everyday life, previous emperors and Romans with wealth such as Trajan had also constructed a villa. Many villas were also self sustaining with small farms and did not need to import food.

The picturesque landscape around Tibur had made the area a popular choice for villas and rural retreats. It was reputedly popular with people from the Spanish peninsula who were residents in the city of Rome. This may have contributed to Hadrian’s choice of the property – although born in Rome, his parents came from Spain and he may have been familiar with the area during his early life.

There may also have been a connection through his wife Vibia Sabina (83–136/137) who was the niece of the Emperor Trajan. Sabina’s family held large landholdings and it is speculated the Tibur property may have been one of them. A villa from the Republican era formed the basis for Hadrian’s establishment.

During the later years of his reign, Hadrian actually governed the empire from the villa. Hadrian started using the villa as his official residence around AD 128. A large court therefore lived there permanently and large numbers of visitors and bureaucrats would have to have been entertained and temporarily housed on site. The postal service kept it in contact with Rome 29 kilometres (18 mi) away, where the various government departments were located.

It isn’t known if Hadrian’s wife lived at the villa either on a temporary or permanent basis – his relations with her were apparently rather strained or distant, possibly due to his ambiguous sexuality. Hadrian’s parents had died when he was young, and he and his sister were adopted by Trajan. It is possible that Hadrian’s court at the villa was predominately male but it’s likely that his childhood nurse Germana, to whom he had formed a deep attachment, was probably accommodated there (she actually outlived him).

After Hadrian, the villa was occasionally used by his various successors (busts of Antoninus Pius (138–161), Marcus Aurelius (161–180), Lucius Verus (161–169), Septimius Severus and Caracalla have been found on the premises). Zenobia, the deposed queen of Palmyra, possibly lived here in the 270s.

During the decline of the Roman Empire in the 4th century, the villa gradually fell into disuse and was partially ruined as valuable statues and marble were taken away. The facility was used as a warehouse by both sides during the destructive Gothic War (535–554) between the Ostrogoths and Byzantines. Remains of lime kilns have been found, where marble from the complex was burned to extract lime for building material.

In the 16th century, Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este had much of the remaining marble and statues in Hadrian’s Villa removed to decorate his own Villa d’Este located nearby. Since that period excavations have sporadically turned up more fragments and sculptures, some of which have been kept in situ or housed on site in the display buildings.

Structure and architecture

Hadrian’s Villa is a vast area of land with many pools, baths, fountains and classical Greek architecture set in what would have been a mixture of landscaped gardens, wilderness areas and cultivated farmlands.

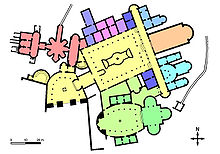

The buildings are constructed in travertine, brick, lime, pozzolana, and tufa. The complex contains over 30 buildings, covering an area of at least a square kilometre (250 acres) of which much is still unexcavated.

The site was chosen due to its abundant waters and readily available aqueducts that passed through Rome, including Anio Vetus, Anio Nobus, Aqua Marcia, and Aqua Claudia.[1] The area was known as the location of villas before Hadrian obtained the property – it was, and still is, a picturesque area conveniently close to Rome but seemingly detached and separate.

The villa was the greatest Roman example of an Alexandrian garden, recreating a sacred landscape.

Giacobbe Giusti, Hadrian’s Villa

The villa shows echoes of many different architectural styles, mostly Greek and Egyptian. Hadrian, a very well-traveled emperor, borrowed these designs, such as the caryatids by the Canopus, along with the statues beside them depicting the Egyptian dwarf and fertility god, Bes. A Greek so called “Maritime Theatre”, also known as the Island Enclosure, exhibits classical ionic style, whereas the domes of the main buildings as well as the Corinthian arches of the Canopus and Serapeum show clear Roman architecture. Hadrian’s biography states that areas in the villa were named after places Hadrian saw during his travels. Only a few places mentioned in the biography can be accurately correlated with the present-day ruins.

One of the most striking and best preserved parts of the Villa consists of a pool named Canopus and an artificial grotto named Serapeum. An Egyptian city named Canopus was where a temple named Serapeum was dedicated to the god Serapis. However, the architecture is Greek influenced (typical in Roman architecture of the High and Late Empire) as seen in the Corinthian columns and the copies of famous Greek statues that surround the pool. The pool measured 119 by 18 metres (390 by 59 ft). Each column surrounding the pool was connected to each other with marble.[2] One anecdote involves the Serapeum and its peculiarly-shaped dome. A prominent architect of the day, Apollodorus of Damascus, dismisses Hadrian’s designs, comparing the dome on Serapeum to a “pumpkin”. The full quote is “Go away and draw your pumpkins. You know nothing about these [architectural] matters.”

Hadrian’s Pecile located inside the Villa was a huge garden surrounded by a swimming pool and an arcade. The pool’s dimensions measure 232 by 97 metres (761 by 318 ft). Originally, the pool was surrounded by four walls with colonnaded interior. These columns helped to support the roof. In the center of the quadriportico was a large rectangular pool. The four walls create a peaceful solitude for Hadrian and guests.

One structure in the villa is the so-called “Maritime Theatre”. It consists of a round portico with a barrel vault supported by pillars. Inside the portico was a ring-shaped pool with a central island. The large circular enclosure 40 metres (130 ft) in diameter has an entrance to the north. Inside the outer wall and surrounding the moat are a ring of unfluted ionic columns. The Maritime Theater includes a lounge, a library, heated baths, three suites with heated floors, washbasin, an art gallery, and a large fountain.[2] During the ancient times, the island was connected to the portico by two wooden drawbridges. On the island sits a small Roman house complete with an atrium, a library, a triclinium, and small baths. The area was probably used by the emperor as a retreat from the busy life at the court.

The villa utilizes numerous architectural styles and innovations. The domes of the steam baths have circular holes on the apex to allow steam to escape. This is reminiscent of the Pantheon, also built by Hadrian. The area has a network of underground tunnels. The tunnels were mostly used to transport servants and goods from one area to another.

In 1998, the remains of what archaeologists claimed to be the monumental tomb of Antinous, or a temple to him, were discovered at the Villa.[3] This, however, has subsequently been challenged in a study noting the lack of any direct evidence for a tomb of Antinous, as well as a previously overlooked patristic source indicating burial in Egypt at Antinopolis, and treating the possibility of a sanctuary of Antinous at Hadrian’s Villa as plausible but unproven.[4]

Giacobbe Giusti, Hadrian’s Villa

In September 2013, a network of tunnels was investigated, buried deep beneath the villa – these were probably service routes for staff so that the idyllic nature of the landscape might remain undisturbed. The site housed several thousand people including staff, visitors, servants and slaves. Although much major activity would have been engaged in during Hadrian’s absence on tours of inspection of the provinces a great many people (and animals) must have been moving about the Tivoli site on a daily basis. The almost constant building activity on top of basic gardening and domestic activities probably led to subterranean routes being resorted to.

The villa itself has been described as an architectural masterpiece. A team of caving specialists has discovered that it is even more impressive than previously thought.[5]

Sculptures and artworks

Giacobbe Giusti, Hadrian’s Villa

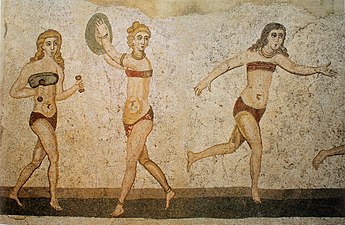

Theatrical masks of Tragedy and Comedy in refined mosaic, from the villa (Capitoline Museum, Rome)

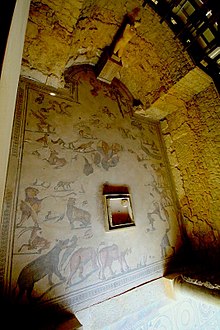

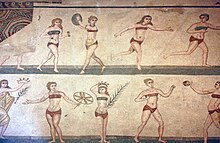

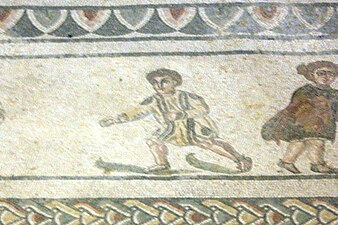

Many beautiful artifacts have been unearthed and restored at the Villa, such as marble statues of Antinous, Hadrian‘s deified lover, accidentally drowned in Egypt, and mosaics from the theatre and baths.[citation needed]

A lifelike mosaic depicted a group of doves around a bowl, with one drinking, seems to be a copy of a work by Sosus of Pergamon as described by Pliny the Elder. It has in turn been widely copied.[6]

Many copies of Greek statues (such as the Wounded Amazon) have been found, and even Egyptian-style interpretations of Roman gods and vice versa. Most of these have been taken to Rome for preservation and restoration, and can be seen at the Musei Capitolini or the Musei Vaticani. However, many were also excavated in the 18th century by antiquities dealers such as Piranesi and Gavin Hamilton to sell to Grand Tourists and antiquarians such as Charles Towneley, and so are in major antiquities collections elsewhere in Europe and North America.

Artworks found in the villa include:

- Discobolus

- Dove Basin mosaic, copy of a famous Hellenistic mosaic, Capitoline Museums

- Diana of Versailles, Louvre

- Crouching Venus

- Capitoline Antinous

- Young Centaur and Old Centaur (Capitoline versions)

Present-day significance

Hadrian’s Villa is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and important cultural and archaeological site. It is also a major tourist destination along with the nearby Villa d’Este and the town of Tivoli. The Academy of the villa was placed on the 100 Most Endangered Sites 2006 list of the World Monuments Watch because of the rapid deterioration of the ruins.

Giacobbe Giusti, Hadrian’s Villa

References

|

|

- Jump up^ “The Emperor’s Abode: Hadrian’s Villa”. Italia. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “View Article: Hadrian’s Villa: A Roman Masterpiece”.

- Jump up^ Mari, Zaccaria and Sgalambro, Sergio: The Antinoeion of Hadrian’s Villa: Interpretation and Architectural Reconstruction, American Journal of Archaeology, Vol 3, No 1, Jan 2007.

- Jump up^ Renberg, Gil H.: Hadrian and the Oracles of Antinous (SHA,Hadr. 14.7); with an appendix on the so-called Antinoeion at Hadrian’s Villa and Rome’s Monte Pincio Obelisk, Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, Vol. 55 (2010) [2011], 159-198.

- Jump up^ “Deep inside tunnels revealed under Hadrian’s Roman villa”. BBC News.

- Jump up^ Drabble, Margaret (2009-09-16). The Pattern in the Carpet: A Personal History with Jigsaws. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-547-24144-9. Retrieved 2012-10-24.

- Jump up^ “Hadrian’s Villa: A Virtual Tour”. Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

Further reading

- A. Betori, Z. Mari, ‘Villa Adriana, edificio circolare noto come Sepolcro o Tomba: campagna di scavo 2004: breve sintesi dei resultati’, in Journal of Fasti Online, http://www.fastionline.org/docs/2004-14.pdf

- Hadrien empereur et architecte. La Villa d’Hadrien: tradition et modernite d’un paysage culturel. Actes du Colloque international organise par le Centre Culturel du Pantheon (2002. Geneva)

- Villa Adriana. Paesaggio antico e ambiente moderno: elementi di novita` e ricerche in corso. Atti del Convegno: Roma 23-24 giugnio 2000, ed. A. M. Reggiani (2002. Milan)

- E. Salza Prina Ricotti, Villa Adriana il sogno di un imperatore (2001)

- Hadrien: tresor d’une villa imperiale, ed. J. Charles-Gaffiot, H. Lavagne [exhibition catalogue, Paris] (1999. Milan)

- W. L. MacDonald and J. A. Pinto, Hadrian’s Villa and its legacy (1995)

- A. Giubilei, ‘Il Conte Fede e la Villa Adriana: storia di una collezione d’arte’, in Atti e Memorie della Società Tiburtina di Storia e d’arte; 68 (1995), p. 81-121

- J. Raeder, Die Statuarische Ausstattung Der Villa Hadriana Bei Tivoli (1983)

- R. Lanciani, La Villa Adriana (1906)[1]