Giacobbe Giusti, Early Medieval Europe

Giacobbe Giusti, Early Medieval Europe

Justinian, Mosaikdetail aus der Kirche San Vitale in Ravenna

Giacobbe Giusti, Early Medieval Europe

Das Karolingerreich zur Zeit Karls des Großen und die späteren Teilreiche

Giacobbe Giusti, Early Medieval Europe

Detail of the votive crown of Visigoth king Reccesuinth († 672). Made of gold and precious stones in the 2nd half of the 7th century. It’s part of the so-called Treasure of Guarrazar.

Giacobbe Giusti, Early Medieval Europe

Giacobbe Giusti, Early Medieval Europe

L’« Europe » à la veille de l’an mille ; un demi-millénaire de transition lui a donné un visage nouveau. Les aires culturelles sont durablement installées, l’héritage romain se perpétue dans les deux empires qui se le disputent, le Saint-Empire romain germanique qui perpétue la culture latinetrès présente dans les monastères et dans l’église de Rome, et l’Empire romain d’Orient qui perpétue la culture grecque très présente dans les églises orientales.

Giacobbe Giusti, Early Medieval Europe

Giacobbe Giusti, Early Medieval Europe

Giacobbe Giusti, Early Medieval Europe

Vikingos daneses invadiendo Inglaterra. Ilustración del siglo XII.

Giacobbe Giusti, Early Medieval Europe

Giustiniano, mosaico nella chiesa di San Vitale a Ravenna

Giacobbe Giusti, Early Medieval Europe

Rilievo dell’altare del Duca Rachis, arte longobarda, 730-740, Museo diocesano cristiano e del tesoro del duomo di Cividale del Friuli

Giacobbe Giusti, Early Medieval Europe

Croce nastriforme, VII secolo, 10 cm, Verona, Museo di Castel Vecchio

Giacobbe Giusti, Early Medieval Europe

Giacobbe Giusti, Early Medieval Europe

Charlemagne’s empire included most of modern France, Germany,

the Low Countries, Austria and northern Italy.

- Balkan Peninsula / Western Asia

- Northern Europe / Scandinavian Peninsula

- Eastern Europe

|

- British Isles

- Italian peninsula

- Iberian peninsula

|

The Early Middle Ages or Early Medieval Period, typically regarded as lasting from the 5th or 6th century to the 10th century CE,[1] marked the start of the Middle Ages of European history. The term “Late Antiquity” is used to emphasize elements of continuity with the Roman Empire, while “Early Middle Ages” is used to emphasize developments characteristic of the later medieval period. As such it overlaps with Late Antiquity, following the decline of the Western Roman Empire, and precedes the High Middle Ages (c. 10th to 13th centuries).

The period saw a continuation of trends evident since late classical antiquity, including population decline, especially in urban centres, a decline of trade, a small rise in global warming and increased migration. The Early Middle Ages was labelled the “Dark Ages” in the 19th century, a characterization based on the relative scarcity of literary and cultural output from this time. However, the Eastern Roman Empire, or Byzantine Empire, continued to survive, though in the 7th century the Islamic caliphates conquered swathes of formerly Roman territory.

Many of these trends were reversed later in the period. In 800 the title of emperor was revived in Western Europe by Charlemagne, whose Carolingian Empire greatly affected later European social structure and history. Europe experienced a return to systematic agriculture in the form of the feudal system which introduced such innovations as three-field planting and the heavy plough. Barbarian migration stabilized in much of Europe, although the north was greatly affected by the Viking expansion.

History

Collapse of Rome

Starting in the 2nd century, various indicators of Roman civilization began to decline, including urbanization, seaborne commerce, and population. Archaeologists have identified only 40 per cent as many Mediterranean shipwrecks from the 3rd century as from the first.[2]Estimates of the population of the Roman Empire during the period from 150 to 400 suggest a fall from 65 million to 50 million, a decline of more than 20 per cent. Some scholars have connected this de-population to the Dark Ages Cold Period (300–700), when a decrease in global temperatures impaired agricultural yields.[3][4]

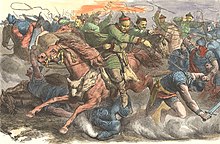

Die Hunnen im Kampf mit den Alanen, (The Huns in battle with the Alans by Johann Nepomuk Geiger, 1873). The Alans, an Iranian peoplewho lived north and east of the Black Sea, functioned as Europe’s first line of defence against the Asiatic Huns.[citation needed] They were dislocated and settled throughout the Roman Empire

Early in the 3rd century Germanic peoples migrated south from Scandinavia and reached the Black Sea, creating formidable confederations which opposed the local Sarmatians. In Dacia (present-day Romania) and on the steppes north of the Black Sea the Goths, a Germanic people, established at least two kingdoms: Therving and Greuthung.[5]

The arrival of the Huns in 372–375 ended the history of these kingdoms. The Huns, a confederation of central Asian tribes, founded an empire. They had mastered the difficult art of shooting composite recurve bows from horseback. The Goths sought refuge in Roman territory (376), agreeing to enter the Empire as unarmed settlers. However many bribed the Danube border-guards into allowing them to bring their weapons.

The discipline and organization of a Roman legion made it a superb fighting unit. The Romans preferred infantry to cavalry because infantry could be trained to retain the formation in combat, while cavalry tended to scatter when faced with opposition. While a barbarian army could be raised and inspired by the promise of plunder, the legions required a central government and taxation to pay for salaries, constant training, equipment, and food. The decline in agricultural and economic activity reduced the empire’s taxable income and thus its ability to maintain a professional army to defend itself from external threats.

The Barbarians’ Invasions

Giacobbe Giusti, Early Medieval Europe

The destruction of the Gothic kingdoms by the

Huns in 372–375 triggered the Germanic migrations of the 5th century. The

Visigoths captured and looted the city of Rome in 410; the

Vandals followed suit in 455

- Germanic tribes

|

- Roman Empire

|

In the Gothic War (376–382), the Goths revolted and confronted the main Roman army in the Battle of Adrianople (378). By this time, the distinction in the Roman army between Roman regulars and barbarian auxiliaries had broken down, and the Roman army comprised mainly barbarians and soldiers recruited for a single campaign. The general decline in discipline also led to the use of smaller shields and lighter weaponry.[6] Not wanting to share the glory, Eastern Emperor Valensordered an attack on the Therving infantry under Fritigern without waiting for Western Emperor Gratian, who was on the way with reinforcements. While the Romans were fully engaged, the Greuthung cavalry arrived. Only one-third of the Roman army managed to escape. This represented the most shattering defeat that the Romans had suffered since the Battle of Cannae (216 BCE), according to the Roman military writer Ammianus Marcellinus.[7] The core army of the Eastern Roman Empire was destroyed, Valens was killed, and the Goths were freed to lay waste to the Balkans, including the armories along the Danube. As Edward Gibbon comments, “The Romans, who so coolly and so concisely mention the acts of justice which were exercised by the legions, reserve their compassion and their eloquence for their own sufferings, when the provinces were invaded and desolated by the arms of the successful Barbarians.”[8]

The empire lacked the resources, and perhaps the will, to reconstruct the professional mobile army destroyed at Adrianople, so it had to rely on barbarian armies to fight for it. The Eastern Roman Empiresucceeded in buying off the Goths with tribute. The Western Roman Empire proved less fortunate. Stilicho, the western empire’s half-Vandal military commander, stripped the Rhine frontier of troops to fend off invasions of Italy by the Visigoths in 402–03 and by other Goths in 406–07.

Fleeing before the advance of the Huns, the Vandals, Suebi, and Alans launched an attack across the frozen Rhine near Mainz; on 31 December, 406, the frontier gave way and these tribes surged into Roman Gaul. There soon followed the Burgundians and bands of the Alamanni. In the fit of anti-barbarian hysteria which followed, the Western Roman Emperor Honorius had Stilicho summarily beheaded (408). Stilicho submitted his neck, “with a firmness not unworthy of the last of the Roman generals“, wrote Gibbon. Honorius was left with only worthless courtiers to advise him. In 410, the Visigoths led by Alaric Icaptured the city of Rome and for three days fire and slaughter ensued as bodies filled the streets, palaces were stripped of their valuables, and the invaders interrogated and tortured those citizens thought to have hidden wealth. As newly converted Christians, the Goths respected church property, but those who found sanctuary in the Vatican and in other churches were the fortunate few.

Migration Period

Migration Period

Around 500, the

Visigoths ruled large parts of what is now France, Spain, Andorra and Portugal.

The Roman Empire was not “conquered” by Germanic tribes, but overrun and even completely displaced by the flood of Germanic migrants. The Goths and Vandals were only the first of many waves of invaders that flooded Western Europe. Some lived only for war and pillage and disdained Roman ways. Other peoples had been in prolonged contact with the Roman civilization, and were, to a certain degree, romanized. “A poor Roman plays the Goth, a rich Goth the Roman” said King Theoderic of the Ostrogoths.[9] The subjects of the Roman empire were a mix of Catholic Christian, Arian Christian, Nestorian Christian, and pagan. The Germanic peoples knew little of cities, money, or writing, and were still mostly pagan, though were becoming increasingly Arian. Arianism was a branch of Christianity that was first proposed early in the 4th century by the Alexandrian presbyter Arius. Arius proclaimed that Christ is not truly divine but a created being. His basic premise was the uniqueness of God, who is alone self-existent and immutable; the Son, who is not self-existent, cannot be God.

During the migrations, or Völkerwanderung (wandering of the peoples), the earlier settled populations were sometimes left intact though usually partially or entirely displaced. Roman culture north of the Po River was almost entirely displaced by the migrations. Whereas the peoples of France, Italy, and Spain continued to speak the dialects of Latin that today constitute the Romance languages, the language of the smaller Roman-era population of what is now England disappeared with barely a trace in the territories settled by the Anglo-Saxons, although the Brittanic kingdoms of the west remained Brythonic speakers. The new peoples greatly altered established society, including law, culture, religion, and patterns of property ownership.

The pax Romana had provided safe conditions for trade and manufacture, and a unified cultural and educational milieu of far-ranging connections. As this was lost, it was replaced by the rule of local potentates, sometimes members of the established Romanized ruling elite, sometimes new lords of alien culture. In Aquitania, Gallia Narbonensis, southern Italy and Sicily, Baetica or southern Spain, and the Iberian Mediterranean coast, Roman culture lasted until the 6th or 7th centuries.

The gradual breakdown and transformation of economic and social linkages and infrastructure resulted in increasingly localized outlooks. This breakdown was often fast and dramatic as it became unsafe to travel or carry goods over any distance; there was a consequent collapse in trade and manufacture for export. Major industries that depended on trade, such as large-scale pottery manufacture, vanished almost overnight in places like Britain. Tintagel in Cornwall, as well as several other centres, managed to obtain supplies of Mediterranean luxury goods well into the 6th century, but then lost their trading links. Administrative, educational and military infrastructure quickly vanished, and the loss of the established cursus honorum led to the collapse of the schools and to a rise of illiteracy even among the leadership. The careers of Cassiodorus (died c. 585) at the beginning of this period and of Alcuin of York (died 804) at its close were founded alike on their valued literacy. For the formerly Roman area, there was another 20 per cent decline in population between 400 and 600, or a one-third decline for 150-600.[10] In the 8th century, the volume of trade reached its lowest level. The very small number of shipwrecksfound that dated from the 8th century supports this (which represents less than 2 per cent of the number of shipwrecks dated from the 1st century). There were also reforestation and a retreat of agriculture centred around 500.

The Romans had practiced two-field agriculture, with a crop grown in one field and the other left fallow and ploughed under to eliminate weeds. Systematic agriculture largely disappeared and yields declined. It is estimated that the Plague of Justinian which began in 541 and recurred periodically for 150 years thereafter killed as many as 100 million people across the world.[11][12] Some historians such as Josiah C. Russell (1958) have suggested a total European population loss of 50 to 60 per cent between 541 and 700.[13] After the year 750, major epidemic diseases did not appear again in Europe until the Black Death of the 14th century. The disease Smallpox, which was eradicated in the late 20th century, did not definitively enter Western Europe until about 581 when Bishop Gregory of Tours provided an eyewitness account that describes the characteristic findings of smallpox.[14] Waves of epidemics wiped out large rural populations.[15]Most of the details about the epidemics are lost, probably due to the scarcity of surviving written records.

For almost a thousand years, Rome was the most politically important, richest and largest city in Europe.[16] Around 100 CE, it had a population of about 450,000,[17] and declined to a mere 20,000 during the Early Middle Ages, reducing the sprawling city to groups of inhabited buildings interspersed among large areas of ruins and vegetation.

Byzantine Empire

The death of Theodosius I in 395 was followed by the division of the empire between his two sons. The Western Roman Empiredisintegrated into a mosaic of warring Germanic kingdoms in the 5th century, making the Eastern Roman Empire in Constantinople the legal successor to the classical Roman Empire. After Greek replaced Latin as the official language of the Empire, historians refer to the empire as “Byzantine”. Westerners would gradually begin to refer to it as “Greek” rather than “Roman”. The inhabitants, however, always called themselves Romaioi, or Romans.

The Eastern Roman Empire aimed to retain control of the trade routes between Europe and the Orient, which made the Empire the richest polity in Europe. Making use of their sophisticated warfare and superior diplomacy, the Byzantines managed to fend off assaults by the migrating barbarians. Their dreams of subduing the Western potentates briefly materialized during the reign of Justinian I in 527–565. Not only did Justinian restore some western territories to the Roman Empire, but he also codified Roman law (with his codificationremaining in force in many areas of Europe until the 19th century) and built the largest and the most technically advanced edifice of the Early Middle Ages, the Hagia Sophia. A bubonic plague pandemic,[18][19] the Plague of Justinian, marred Justinian’s reign, however, infecting the Emperor, killing perhaps 40% of the population of Constantinople.

Justinian’s successors Maurice and Heracliusconfronted invasions by the Avar and Slavic tribes. After the devastations by the Slavs and the Avars, large areas of the Balkans became depopulated. In 626 Constantinople, by far the largest city of early medieval Europe, withstood a combined siege by Avars and Persians. Within several decades, Heraclius completed a holy war against the Persians, taking their capital and having a Sassanid monarch assassinated. Yet Heraclius lived to see his spectacular success undone by the Muslim conquests of Syria, three Palaestina provinces, Egypt, and North Africa which was considerably facilitated by religious disunity and the proliferation of heretical movements (notably Monophysitism and Nestorianism) in the areas converted to Islam.

Although Heraclius’s successors managed to salvage Constantinople from two Arab sieges (in 674–77 and 717), the empire of the 8th and early 9th century was rocked by the great Iconoclastic Controversy, punctuated by dynastic struggles between various factions at court. The Bulgar and Slavic tribes profited from these disorders and invaded Illyria, Thrace and even Greece. After the decisive victory at Ongala in 680 the armies of the Bulgars and Slavs advanced to the south of the Balkan mountains, defeating again the Byzantines who were then forced to sign a humiliating peace treaty which acknowledged the establishment of the First Bulgarian Empireon the borders of the Empire.

To counter these threats a new system of administration was introduced. The regional civil and military administration were combined in the hands of a general, or strategos. A theme, which formerly denoted a subdivision of the Byzantine army, came to refer to a region governed by a strategos. The reform led to the emergence of great landed families which controlled the regional military and often pressed their claims to the throne (see Bardas Phocas and Bardas Sklerus for characteristic examples).

By the early 8th century, notwithstanding the shrinking territory of the empire, Constantinople remained the largest and the wealthiest city of the entire world, comparable only to Sassanid Ctesiphon, and later Abassid Baghdad. The population of the imperial capital fluctuated between 300,000 and 400,000 as the emperors undertook measures to restrain its growth. The only other large Christian cities were Rome (50,000) and Salonika (30,000).[21] Even before the 8th century was out, the Farmer’s Law signalled the resurrection of agricultural technologies in the Roman Empire. As the 2006 Encyclopædia Britannica noted, “the technological base of Byzantine society was more advanced than that of contemporary western Europe: iron tools could be found in the villages; water mills dotted the landscape; and field-sown beans provided a diet rich in protein”.[22]

The ascension of the Macedonian dynasty in 867 marked the end of the period of political and religious turmoil and introduced a new golden age of the empire. While the talented generals such as Nicephorus Phocas expanded the frontiers, the Macedonian emperors (such as Leo the Wise and Constantine VII) presided over the cultural flowering in Constantinople, known as the Macedonian Renaissance. The enlightened Macedonian rulers scorned the rulers of Western Europe as illiterate barbarians and maintained a nominal claim to rule over the West. Although this fiction had been exploded with the coronation of Charlemagne in Rome (800), the Byzantine rulers did not treat their Western counterparts as equals. Generally, they had little interest in political and economic developments in the barbarian (from their point of view) West.

Against this economic background the culture and the imperial traditions of the Eastern Roman Empire attracted its northern neighbours—Slavs, Bulgars, and Khazars—to Constantinople, in search of either pillage or enlightenment. The movement of the Germanic tribes to the south triggered the great migration of the Slavs, who occupied the vacated territories. In the 7th century, they moved westward to the Elbe, southward to the Danube and eastward to the Dnieper. By the 9th century, the Slavs had expanded into sparsely inhabited territories to the south and east from these natural frontiers, peacefully assimilating the indigenous Illyrian and Finno-Ugricpopulations.

Rise of Islam

- 632–750

From the 7th century Byzantine history was greatly affected by the rise of Islam and the Caliphates. Muslim Arabs first invaded historically Roman territory under Abū Bakr, first Caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate, who entered Roman Syria and Roman Mesopotamia. The Byzantines and neighbouring Persian Sasanids had been severely weakened by a long succession of Byzantine–Sasanian wars, especially the climactic Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628. Under Umar, the second Caliph, the Muslims decisively conquered Syria and Mesopotamia, as well as Roman Palestine, Roman Egypt, parts of Asia Minor and Roman North Africa, while they entirely toppled the Sasanids. In the mid 7th century AD, following the Muslim conquest of Persia, Islam penetrated into the Caucasus region, of which parts would later permanently become part of Russia.[23] This expansion of Islam continued under Umar’s successors and then the Umayyad Caliphate, which conquered the rest of Mediterranean North Africa and most of the Iberian Peninsula. Over the next centuries Muslim forces were able to take further European territory, including Cyprus, Malta, Septimania, Crete, and Sicily and parts of southern Italy.[24]

The Muslim conquest of Hispania began when the Moors (mostly Berbers and some Arabs) invaded the Christian Visigothic kingdom of Iberia in the year 711, under their Berber leader Tariq ibn Ziyad. They landed at Gibraltar on 30 April and worked their way northward. Tariq’s forces were joined the next year by those of his superior, Musa ibn Nusair. During the eight-year campaign most of the Iberian Peninsulawas brought under Muslim rule—except for small areas in the north-northwest (Asturias) and largely Basque regions in the Pyrenees. This territory, under the Arab name Al-Andalus, became part of the expanding Umayyad empire.

The unsuccessful second siege of Constantinople (717) weakened the Umayyad dynasty and reduced their prestige. After their success in overrunning Iberia, the conquerors moved northeast across the Pyrenees. They were defeated by the Frankish leader Charles Martelat the Battle of Poitiers in 732. The Umayyads were overthrown in 750 by the Abbāsids and most of the Umayyad clan were massacred.

A surviving Umayyad prince, Abd-ar-rahman I, escaped to Spain and founded a new Umayyad dynasty in the Emirate of Cordoba in 756. Charles Martel’s son Pippin the Short retook Narbonne, and his grandson Charlemagne established the Marca Hispanica across the Pyrenees in part of what today is Catalonia, reconquering Girona in 785 and Barcelona in 801. The Umayyads in Spain proclaimed themselves caliphs in 929.

Birth of the Latin West

700–850

Due to a complex set of reasons,[which?] conditions in Western Europe began to improve after 700.[3][25] In that year, the two major powers in western Europe were the Franks in Gaul and the Lombards in Italy.[26] The Lombards had been thoroughly Romanized, and their kingdom was stable and well developed. The Franks, in contrast, were barely any different from their barbarian Germanic ancestors. Their kingdom was weak and divided.[27] Impossible to guess at the time, but by the end of the century, the Lombardic kingdom would be extinct, while the Frankish kingdom would have nearly reassembled the Western Roman Empire.[26]

Though much of Roman civilization north of the Po River had been wiped out in the years after the end of the Western Roman Empire, between the 5th and 8th centuries, new political and social infrastructure began to develop. Much of this was initially Germanic and pagan. Arian Christian missionaries had been spreading Arian Christianity throughout northern Europe, though by 700 the religion of northern Europeans was largely a mix of Germanic paganism, Christianized paganism, and Arian Christianity.[28] Catholic Christianity had barely started to spread in northern Europe by this time. Through the practice of simony, local princes typically auctioned off ecclesiastical offices, causing priests and bishops to function as though they were yet another noble under the patronage of the prince.[29] In contrast, a network of monasteries had sprung up as monks sought separation from the world. These monasteries remained independent from local princes, and as such constituted the “church” for most northern Europeans during this time. Being independent from local princes, they increasingly stood out as centres of learning, of scholarship, and as religious centres where individuals could receive spiritual or monetary assistance.[28]

The interaction between the culture of the newcomers, their warband loyalties, the remnants of classical culture, and Christian influences, produced a new model for society, based in part on feudal obligations. The centralized administrative systems of the Romans did not withstand the changes, and the institutional support for chattel slavery largely disappeared. The Anglo-Saxons in England had also started to convert from Anglo-Saxon polytheism after the arrival of Christian missionaries around the year 600.

Italy

The Lombard possessions in Italy: The Lombard Kingdom (Neustria, Austria and Tuscia) and the Lombard Duchies of Spoleto and Benevento

The Lombards, who first entered Italy in 568 under Alboin, carved out a state in the north, with its capital at Pavia. At first, they were unable to conquer the Exarchate of Ravenna, the Ducatus Romanus, and Calabriaand Apulia. The next two hundred years were occupied in trying to conquer these territories from the Byzantine Empire.

The Lombard state was relatively Romanized, at least when compared to the Germanic kingdoms in northern Europe. It was highly decentralized at first, with the territorial dukes having practical sovereignty in their duchies, especially in the southern duchies of Spoleto and Benevento. For a decade following the death of Cleph in 575, the Lombards did not even elect a king; this period is called the Rule of the Dukes. The first written legal code was composed in poor Latin in 643: the Edictum Rothari. It was primarily the codification of the oral legal tradition of the people.

The Lombard state was well-organized and stabilized by the end of the long reign of Liutprand (717–744), but its collapse was sudden. Unsupported by the dukes, King Desiderius was defeated and forced to surrender his kingdom to Charlemagne in 774. The Lombard kingdom ended and a period of Frankish rule was initiated. The Frankish king Pepin the Short had, by the Donation of Pepin, given the pope the “Papal States” and the territory north of that swath of papally-governed land was ruled primarily by Lombard and Frankish vassals of the Holy Roman Emperor until the rise of the city-states in the 11th and 12th centuries.

In the south, a period of chaos began. The duchy of Benevento maintained its sovereignty in the face of the pretensions of both the Western and Eastern Empires. In the 9th century, the Muslimsconquered Sicily. The cities on the Tyrrhenian Sea departed from Byzantine allegiance. Various states owing various nominal allegiances fought constantly over territory until events came to a head in the early 11th century with the coming of the Normans, who conquered the whole of the south by the end of the century.

Britain

Roman Britain was in a state of political and economic collapse at the time of the Roman departure c. 400. A series of settlements(traditionally referred to as an invasion) by Germanic peoples began in the early fifth century, and by the sixth century the island would consist of many small kingdoms engaged in ongoing warfare with each other. The Germanic kingdoms are now collectively referred to as Anglo-Saxons. Christianization began to take hold among the Anglo-Saxons in the sixth century, with 597 given as the traditional date for its large-scale adoption.

The Gokstad ship, a 9th-century Viking longship, excavated in 1882. Viking Ship Museum, Oslo, Norway

Western Britain (Wales), eastern and northern Scotland (Pictland) and the Scottish highlands and isles continued their separate evolution. The Irish descended and Irish-influenced people of western Scotland were Christian from the fifth century onward, the Picts adopted Christianity in the sixth century under the influence of Columba, and the Welsh had been Christian since the Roman era.

Northumbria was the pre-eminent power c. 600–700, absorbing several weaker Anglo-Saxon and Brythonickingdoms, while Mercia held a similar status c. 700–800. Wessexwould absorb all of the kingdoms in the south, both Anglo-Saxon and Briton. In Wales consolidation of power would not begin until the ninth century under the descendants of Merfyn Frych of Gwynedd, establishing a hierarchy that would last until the Norman invasion of Wales in 1081.

The first Viking raids on Britain began before 800, increasing in scope and destructiveness over time. In 865 a large, well-organized DanishViking army (called the Great Heathen Army) attempted a conquest, breaking or diminishing Anglo-Saxon power everywhere but in Wessex. Under the leadership of Alfred the Great and his descendants, Wessex would at first survive, then coexist with, and eventually conquer the Danes. It would then establish the Kingdom of England and rule until the establishment of an Anglo-Danish kingdom under Cnut, and then again until the Norman Invasion of 1066.

Viking raids and invasion were no less dramatic for the north. Their defeat of the Picts in 839 led to a lasting Norse heritage in northernmost Scotland, and it led to the combination of the Picts and Gaels under the House of Alpin, which became the Kingdom of Alba, the predecessor of the Kingdom of Scotland. The Vikings combined with the Gaels of the Hebrides to become the Gall-Gaidel and establish the Kingdom of the Isles.

Frankish Empire

Charlemagne’s Coronation

On 25 December 800,

Charlemagne was crowned emperor by

Pope Leo III.

Coronation of Charlemagne, Grandes Chroniques de France, Jean Fouquet, Tours, c. 1455-1460

The Merovingians established themselves in the power vacuum of the former Roman provinces in Gaul, and Clovis I converted to Christianity following his victory over the Alemanni at the Battle of Tolbiac (496), laying the foundation of the Frankish Empire, the dominant state of early medieval Western Christendom. The Frankish kingdom grew through a complex development of conquest, patronage, and alliance building. Due to salic custom, inheritance rights were absolute, and all land was divided equally among the sons of a dead land holder.[30] This meant that, when the king granted a prince land in reward for service, that prince and all of his descendants had an irrevocable right to that land that no future king could undo. Likewise, those princes (and their sons) could sublet their land to their own vassals, who could in turn sublet the land to lower sub-vassals.[30] This all had the effect of weakening the power of the king as his kingdom grew, since the result was that the land became controlled by not just by more princes and vassals, but by multiple layers of vassals. This also allowed his nobles to attempt to build their own power base, though given the strict salic tradition of hereditary kingship, few would ever consider overthrowing the king.[30]

This increasingly absurd arrangement was highlighted by Charles Martel, who as Mayor of the Palace was effectively the strongest prince in the kingdom.[31] His accomplishments were highlighted, not just by his famous defeat of invading Muslims at the Battle of Tours, which is typically considered the battle that saved Europe from Muslim conquest, but by the fact that he greatly expanded Frankish influence. It was under his patronage that Saint Boniface expanded Frankish influence into Germany by rebuilding the German church, with the result that, within a century, the German church was the strongest church in western Europe.[31] Yet despite this, Charles Martel refused to overthrow the Frankish king. His son, Pepin the Short, inherited his power, and used it to further expand Frankish influence. Unlike his father, however, Pepin decided to seize the Frankish kingship. Given how strongly Frankish culture held to its principle of inheritance, few would support him if he attempted to overthrow the king.[32] Instead, he sought the assistance of Pope Zachary, who was himself newly vulnerable due to fallout with the Byzantine Emperor over the Iconoclastic Controversy. Pepin agreed to support the pope and to give him land (the Donation of Pepin, which created the Papal States) in exchange for being consecrated as the new Frankish king. Given that Pepin’s claim to the kingship was now based on an authority higher than Frankish custom, no resistance was offered to Pepin.[32]With this, the Merovingian line of kings ended, and the Carolingian line began.

Pepin’s son Charlemagne continued in the footsteps of his father and grandfather. He further expanded and consolidated the Frankish kingdom (now commonly called the Carolingian Empire). His reign also saw a cultural rebirth, commonly called the Carolingian Renaissance. Though the exact reasons are unclear, Charlemagne was crowned “Roman Emperor” by Pope Leo III on Christmas Day, 800. Upon Charlemagne’s death, his empire had united much of modern-day France, western Germany and northern Italy. The years after his death illustrated how Germanic his empire remained.[32]Rather than an orderly succession, his empire was divided in accordance with Frankish inheritance custom, which resulted in instability that plagued his empire until the last king of a united empire, Charles the Fat, died in 887, which resulted in a permanent split of the empire into West Francia and East Francia. West Francia would be ruled by Carolingians until 987 and East Francia until 911, after which time the partition of the empire into France and Germany was complete.[32]

Feudalism

Around 800 there was a return to systematic agriculture in the form of the open field, or strip, system. A manor would have several fields, each subdivided into 1-acre (4,000 m2) strips of land. An acre measured one “furlong” of 220 yards by one “chain” of 22 yards (that is, about 200 m by 20 m). A furlong (from “furrow long”) was considered to be the distance an ox could plough before taking a rest; the strip shape of the acre field also reflected the difficulty in turning early heavy ploughs. In the idealized form of the system, each family got thirty such strips of land. The three-field system of crop rotationwas first developed in the 9th century: wheat or rye was planted in one field, the second field had a nitrogen-fixing crop, and the third was fallow.[33]

Compared to the earlier two-field system, a three-field system allows for significantly more land to be put under cultivation. Even more important, the system allows for two harvests a year, reducing the risk that a single crop failure will lead to famine. Three-field agriculture creates a surplus of oats that can be used to feed horses. This surplus would allow the replacement of the ox by the horse after the introduction of the padded horse collar in the 12th century. Because the system required a major rearrangement of real estate and of the social order, it took until the 11th century before it came into general use. The heavy wheeled plough was introduced in the late 10th century. It required greater animal power and promoted the use of teams of oxen. Illuminated manuscripts depict two-wheeled ploughs with both a mouldboard, or curved metal ploughshare, and a coulter, a vertical blade in front of the ploughshare. The Romans had used light, wheel-less ploughs with flat iron shares that often proved unequal to the heavy soils of northern Europe.

The return to systemic agriculture coincided with the introduction of a new social system called feudalism. This system featured a hierarchy of reciprocal obligations. Each man was bound to serve his superior in return for the latter’s protection. This made for confusion of territorial sovereignty since allegiances were subject to change over time and were sometimes mutually contradictory. Feudalism allowed the state to provide a degree of public safety despite the continued absence of bureaucracy and written records. Even land ownership disputes were decided based solely on oral testimony. Territoriality was reduced to a network of personal allegiances.

Viking Age[edit]

Scandinavian settlements and raiding territory. Note : yellow in England and southern Italy covers the Viking expansion from Normandy, called by the name of Norman

- 8th century homeland

- 9th century expansion

- 10th century expansion

Viking raiding regions

The Viking Age spans the period roughly between the late 8th and mid-11th centuries in Scandinavia and Britain, following the Germanic Iron Age (and the Vendel Age in Sweden). During this period, the Vikings, Scandinavian warriors and traders raided and explored most parts of Europe, south-western Asia, northern Africa, and north-eastern North America.

With the means to travel (longships and open water), desire for goods led Scandinavian traders to explore and develop extensive trading partnerships in new territories. Some of the most important trading ports during the period include both existing and ancient cities such as Aarhus, Ribe, Hedeby, Vineta, Truso, Kaupang, Birka, Bordeaux, York, Dublin, and Aldeigjuborg.

Viking raiding expeditions were separate from, though coexisted with, regular trading expeditions. Apart from exploring Europe via its oceans and rivers, with the aid of their advanced navigational skills, they extended their trading routes across vast parts of the continent. They also engaged in warfare, looting and enslaving numerous Christian communities of Medieval Europe for centuries, contributing to the development of feudal systems in Europe.

Eastern Europe

- 600–1000

Main articles:

Byzantine Empire,

Western Turkic Khaganate,

Avar Khaganate,

Khazar Khaganate,

Old Great Bulgaria,

Alani,

Magyars,

Early Slavs,

Principality of Serbia (medieval),

Great Moravia, and

Duchy of CroatiaThe Early Middle Ages marked the beginning of the cultural distinctions between Western and Eastern Europe north of the Mediterranean. Influence from the Byzantine Empire impacted the Christianization and hence almost every aspect of the cultural and political development of the East from the preeminence of Caesaropapism and Eastern Christianity to the spread of the Cyrillic alphabet. The turmoil of the so-called Barbarian invasions in the beginning of the period gradually gave way to more stabilized societies and states as the origins of contemporary Eastern Europe began to take shape during the High Middle Ages.

Magyar campaigns in the 10th century

Magyar region

Most European nations were praying for mercy: “Sagittis hungarorum libera nos, Domine” – “Lord save us from the arrows of Hungarians”[citation needed]

Turkic and Iranian invaders from Central Asia pressured the agricultural populations both in the Byzantine Balkans and in Central Europe creating a number of successor states in the Pontic steppes. After the dissolution of the Hunnic Empire, the Western Turkic and Avar Khaganates dominated territories from Pannonia to the Caspian Sea before replaced by the short lived Old Great Bulgaria and the more successful Khazar Khaganate north of the Black Sea and the Magyars in Central Europe.

The Khazars were a nomadic Turkic people who managed to develop a multiethnic commercial state which owed its success to the control of much of the waterway trade between Europe and Central Asia. The Khazars also exacted tribute from the Alani, Magyars, various Slavictribes, the Crimean Goths, and the Greeks of Crimea. Through a network of Jewish itinerant merchants, or Radhanites, they were in contact with the trade emporia of India and Spain.

Once they found themselves confronted by Arab expansionism, the Khazars pragmatically allied themselves with Constantinople and clashed with the Caliphate. Despite initial setbacks, they managed to recover Derbent and eventually penetrated as far south as Caucasian Iberia, Caucasian Albania and Armenia. In doing so, they effectively blocked the northward expansion of Islam into Eastern Europe even before khan Tervel achieved the same at the Second Arab Siege of Constantinople and several decades before the Battle of Tours in Western Europe. Islam eventually penetrated into Eastern Europe in the 920s when Volga Bulgaria exploited the decline of Khazar power in the region to adopt Islam from the Baghdad missionaries. The state religion of Khazaria, Judaism, disappeared as a political force with the fall of Khazaria, while Islam of Volga Bulgaria has survived in the region up to the present.

In the beginning of the period the Slavic tribes started to expand aggressively into Byzantine possessions on the Balkans. The first attested Slavic polities were Serbia and Great Moravia, the latter of which emerged under the aegis of the Frankish Empire in the early 9th century. Great Moravia was ultimately overrun by the Magyars, who invaded the Pannonian Basin around 896. The Slavic state became a stage for confrontation between the Christian missionaries from Constantinople and Rome. Although West Slavs, Croats and Sloveneseventually acknowledged Roman ecclesiastical authority, the clergy of Constantinople succeeded in converting to Eastern Christianity two of the largest states of early medieval Europe, Bulgaria around 864, and Kievan Rus’ circa 990.

Bulgaria[edit]

Ceramic icon of St Theodorefrom around 900, found in Preslav, Bulgarian capital from 893–972

In 632 the Bulgars established the khanate of Old Great Bulgaria under the leadership of Kubrat. The Khazars managed to oust the Bulgars from Southern Ukraine into lands along middle Volga (Volga Bulgaria) and along lower Danube(Danube Bulgaria).

In 681 the Bulgars founded a powerful and ethnically diverse state that played a defining role in the history of early medieval Southeastern Europe. Bulgaria withstood the pressure from Pontic steppe tribes like the Pechenegs, Khazars, and Cumans, and in 806 destroyed the Avar Khanate. The Danube Bulgars were quickly slavicized and, despite constant campaigning against Constantinople, accepted Christianity from the Byzantine Empire. Through the efforts of missionaries Saint Cyril and Saint Methodius,[34] the Bulgarian Glagolitic and Cyrillic alphabets were developed in the capital Preslav and a vernacular dialect, now known as Old Bulgarian or Old Church Slavonic, was established as the language of books and liturgy among Orthodox Christian Slavs.

After the adoption of Christianity in 864, Bulgaria became a cultural and spiritual hub of the Eastern Orthodox Slavic world. The Cyrillic script was developed by Bulgarian scholar Clement of Ohrid in 885-886 and was afterwards introduced to Serbia and Kievan Rus’. Literature, art, and architecture were thriving with the establishment of the Preslav and Ohrid Literary Schools along with the distinct Preslav Ceramics School. In 927 the Bulgarian Orthodox Church was the first European national Church to gain independence with its own Patriarch while conducting services in the vernacular Old Church Slavonic.

Under Simeon I (893–927), the state was the largest and one of the most powerful political entities of Europe, and it consistently threatened the existence of the Byzantine empire. From the middle of the 10th century Bulgaria was in decline as it entered a social and spiritual turmoil. It was in part due to Simeon’s devastating wars, but was also exacerbated by a series of successful Byzantine military campaigns. Bulgaria was conquered after a long resistance in 1018.

Kievan Rus’

Led by a Varangian dynasty, the Kievan Rus’ controlled the routes connecting Northern Europe to Byzantium and to the Orient (for example: the Volga trade route). The Kievan state began with the rule (882–912) of Prince Oleg, who extended his control from Novgorodsouthwards along the Dnieper river valley in order to protect trade from Khazar incursions from the east and moved his capital to the more strategic Kiev. Sviatoslav I (died 972) achieved the first major expansion of Kievan Rus’ territorial control, fighting a war of conquest against the Khazar Empire and inflicting a serious blow on Bulgaria. A Rus’ attack (967 or 968), instigated by the Byzantines, led to the collapse of the Bulgarian state and the occupation of the east of the country by the Rus’. An ensuing direct military confrontation between the Rus’ and Byzantium (970-971) ended with a Byzantine victory(971). The Rus’ withdrew and the Byzantine Empire incorporated eastern Bulgaria. Both before and after their conversion to Christianity(conventionally dated 988 under Vladimir I of Kiev—known as Vladimir the Great), the Rus’ also embarked on predatory military campaigns against the Byzantine Empire, some of which resulted in trade treaties. The importance of Russo-Byzantine relations to Constantinople was highlighted by the fact that Vladimir I of Kiev, son of Svyatoslav I, became the only foreigner to marry (989) a Byzantine princess of the Macedonian dynasty (which ruled the Eastern Roman Empire from 867 to 1056), a singular honour sought in vain by many other rulers.

Transmission of learning

With the end of the Western Roman Empire and with urban centres in decline, literacy and learning decreased in the West. This continued a pattern that had been underway since the 3rd century.[35] Much learning under the Roman Empire was in Greek, and with the re-emergence of the wall between east and west, little eastern learning continued in the west. Much of the Greek literary corpus remained in Greek, and few in the west could speak or read Greek.[35] Due to the demographic displacement that accompanied the end of the western Roman Empire, by this point most western Europeans were descendants of non-literate barbarians rather than literate Romans. In this sense, education was not lost so much as it had yet to be acquired.[35]

Education did ultimately continue, and was centred in the monasteries and cathedrals. A “Renaissance” of classical education would appear in Carolingian Empire in the 8th century. In the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium), learning (in the sense of formal education involving literature) was maintained at a higher level than in the West. The classical education system, which would persist for hundreds of years, emphasized grammar, Latin, Greek, and rhetoric. Pupils read and reread classic works and wrote essays imitating their style. By the 4th century, this education system was Christianized. In De Doctrina Christiana (started 396, completed 426), Augustine explained how classical education fits into the Christian worldview: Christianity is a religion of the book, so Christians must be literate. Tertullian was more skeptical of the value of classical learning, asking “What indeed has Athens to do with Jerusalem?”[36]

De-urbanization reduced the scope of education, and by the 6th century teaching and learning moved to monastic and cathedral schools, with the study of biblical texts at the centre of education.[37]Education of the laity continued with little interruption in Italy, Spain, and the southern part of Gaul, where Roman influences were more long-lasting. In the 7th century, however, learning expanded in Ireland and the Celtic lands, where Latin was a foreign language and Latin texts were eagerly studied and taught.[38]

Science

In the ancient world, Greek was the primary language of science. Advanced scientific research and teaching was mainly carried on in the Hellenistic side of the Roman empire, and in Greek. Late Roman attempts to translate Greek writings into Latin had limited success.[39]As the knowledge of Greek declined, the Latin West found itself cut off from some of its Greek philosophical and scientific roots. For a time, Latin-speakers who wanted to learn about science had access to only a couple of books by Boethius (c. 470–524) that summarized Greek handbooks by Nicomachus of Gerasa. Saint Isidore of Sevilleproduced a Latin encyclopedia in 630. Private libraries would have existed, and monasteries would also keep various kinds of texts.

The study of nature was pursued more for practical reasons than as an abstract inquiry: the need to care for the sick led to the study of medicine and of ancient texts on drugs;[40] the need for monks to determine the proper time to pray led them to study the motion of the stars;[41] and the need to compute the date of Easter led them to study and teach mathematics and the motions of the Sun and Moon.[42][43]

Carolingian Renaissance

In the late 8th century, there was renewed interest in Classical Antiquity as part of the Carolingian Renaissance. Charlemagne carried out a reform in education. The English monk Alcuin of York elaborated a project of scholarly development aimed at resuscitating classical knowledge by establishing programs of study based upon the seven liberal arts: the trivium, or literary education (grammar, rhetoric, and dialectic), and the quadrivium, or scientific education (arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music). From 787 on, decrees began to circulate recommending the restoration of old schools and the founding of new ones across the empire.

Institutionally, these new schools were either under the responsibility of a monastery (monastic schools), a cathedral, or a noble court. The teaching of dialectic (a discipline that corresponds to today’s logic) was responsible for the increase in the interest in speculative inquiry; from this interest would follow the rise of the Scholastic tradition of Christian philosophy. In the 12th and 13th centuries, many of those schools founded under the auspices of Charlemagne, especially cathedral schools, would become universities.

Byzantium’s golden age

Byzantium’s great intellectual achievement was the Corpus Juris Civilis (“Body of Civil Law”), a massive compilation of Roman lawmade under Justinian (r. 528-65). The work includes a section called the Digesta which abstracts the principles of Roman law in such a way that they can be applied to any situation. The level of literacy was considerably higher in the Byzantine Empire than in the Latin West. Elementary education was much more widely available, sometimes even in the countryside. Secondary schools still taught the Iliad and other classics.

As for higher education, the Neoplatonic Academy in Athens was closed in 526. There was also a school in Alexandria which remained open until the Arab conquest (640). The University of Constantinople, founded by Emperor Theodosius II (425), seems to have dissolved around this time. It was refounded by Emperor Michael III in 849. Higher education in this period focused on rhetoric, although Aristotle‘s logic was covered in simple outline. Under the Macedonian dynasty (867–1056), Byzantium enjoyed a golden age and a revival of classical learning. There was little original research, but many lexicons, anthologies, encyclopedias, and commentaries.

Islamic learning

In the course of the 11th century, Islam’s scientific knowledge began to reach Western Europe, via Islamic Spain. The works of Euclid and Archimedes, lost in the West, were translated from Arabic to Latin in Spain. The modern Hindu-Arabic numeral system, including a notation for zero, were developed by Hindu mathematicians in the 5th and 6th centuries. Muslim mathematicians learned of it in the 7th century and added a notation for decimal fractions in the 9th and 10th centuries. Around 1000, Gerbert of Aurillac (later Pope Sylvester II) made an abacus with counters engraved with Arabic numerals. A treatise by Al-Khwārizmī on how to perform calculations with these numerals was translated into Latin in Spain in the 12th century.

Monasteries[edit]

Monasteries were targeted in the eighth and ninth centuries by Vikingswho invaded the coasts of northern Europe. They were targeted not only because they stored books but also precious objects that were looted by invaders. In the earliest monasteries, there were no special rooms set aside as a library, but from the sixth century onwards libraries became an essential aspect of monastic life in the Western Europe. The Benedictines placed books in the care of a librarian who supervised their use. In some monastic reading rooms, valuable books would be chained to shelves, but there were also lending sections as well. Copying was also another important aspect of monastic libraries, this was undertaken by resident or visiting monks and took place in the scriptorium. In the Byzantine world, religious houses rarely maintained their own copying centres. Instead they acquired donations from wealthy donors. In the tenth century, the largest collection in the Byzantine world was found in the monasteries of Mount Athos(modern-day Greece), which accumulated over 10,000 books. Scholars travelled from one monastery to another in search of the texts they wished to study. Travelling monks were often given funds to buy books, and certain monasteries which held a reputation for intellectual activities welcomed travelling monks who came to copy manuscripts for their own libraries. One of these was the monastery of Bobbio in Italy, which was founded by the Irish abbot St. Columba in 614, and by the ninth century boasted a catalogue of 666 manuscripts, including religious works, classical texts, histories and mathematical treatises.[44]

Christianity West and East

From the early Christians, early medieval Christians inherited a church united by major creeds, a stable Biblical canon, and a well-developed philosophical tradition. The history of medieval Christianity traces Christianity during the Middle Ages—the period after the fall of the Roman Empire until the Protestant Reformation. The institutional structure of Christianity in the west during this period is different from what it would become later in the Middle Ages. As opposed to the later church, the church of the early Middle Ages consisted primarily of the monasteries.[45]The practice of simony has caused the ecclesiastical offices to become the property of local princes, and as such the monasteries constituted the only church institution independent of the local princes. In addition, the papacy was relatively weak, and its power was mostly confined to central Italy.[45] Individualized religious practice was uncommon, as it typically required membership in a religious order, such as the Order of Saint Benedict.[45] Religious orders would not proliferate until the high Middle Ages. For the typical Christian at this time, religious participation was largely confined to occasionally receiving mass from wandering monks. Few would be lucky enough to receive this as often as once a month.[45] By the end of this period, individual practice of religion was becoming more common, as monasteries started to transform into something approximating modern churches, where some monks might even give occasional sermons.[45]

During the early Middle Ages, the divide between Eastern and Western Christianity widened, paving the way for the East-West Schism in the 11th century. In the West, the power of the Bishop of Rome expanded. In 607, Boniface III became the first Bishop of Rome to use the title Pope[citation needed]. Pope Gregory the Great used his office as a temporal power, expanded Rome’s missionary efforts to the British Isles, and laid the foundations for the expansion of monastic orders. Roman church traditions and practices gradually replaced local variants, including Celtic Christianity in Great Britain and Ireland. Various barbarian tribes went from raiding and pillaging the island to invading and settling. They were entirely pagan, having never been part of the Empire, though they experienced Christian influence from the surrounding peoples, such as those who were converted by the mission of St. Augustine of Canterbury, sent by Pope Gregory the Great. In the East, the conquests of Islam reduced the power of the Greek-speaking patriarchates.

Christianization of the West

The Catholic Church, the only centralized institution to survive the fall of the Western Roman Empire intact, was the sole unifying cultural influence in the West, preserving Latin learning, maintaining the art of writing, and preserving a centralized administration through its network of bishops ordained in succession. The Early Middle Ages are characterized by the urban control of bishops and the territorial control exercised by dukes and counts. The rise of urban communes marked the beginning of the High Middle Ages.

The Christianization of Germanic tribes began in the 4th century with the Goths and continued throughout the Early Middle Ages, led in the 6th to 7th centuries by the Hiberno-Scottish mission and replaced in the 8th to 9th centuries by the Anglo-Saxon mission, with Anglo-Saxons like Alcuin playing an important role in the Carolingian renaissance. Saint Boniface, the Apostle of the Germans, propagated Christianity in the Frankish Empire during the 8th century. He helped shape Western Christianity, and many of the dioceses he proposed remain until today. After his martyrdom, he was quickly hailed as a saint. By 1000, even Iceland had become Christian, leaving only more remote parts of Europe (Scandinavia, the Baltic, and Finno-Ugriclands) to be Christianized during the High Middle Ages.

Holy Roman Empire

10th century

The Holy Roman Empire

HRE in era from Emperor

Otto I to

Konrad II included present-day: Germany, the Czech Republic, Austria, Slovenia, northern half of Italy, Switzerland, (south)eastern France, Belgium and the Netherlands

- Imperial region

- Other regions

Listless and often ill, Carolingian Emperor Charles the Fat provoked an uprising, led by his nephew Arnulf of Carinthia, which resulted in the division of the empire in 887 into the kingdoms of France, Germany, and (northern) Italy. Taking advantage of the weakness of the German government, the Magyars had established themselves in the Alföld, or Hungarian grasslands, and began raiding across Germany, Italy, and even France. The German nobles elected Henry the Fowler, duke of Saxony, as their king at a Reichstag, or national assembly, in Fritzlar in 919. Henry’s power was only marginally greater than that of the other leaders of the stem duchies, which were the feudal expression of the former German tribes.

Henry’s son King Otto I (r. 936–973) was able to defeat a revolt of the dukes supported by French King Louis IV (939). In 951, Otto marched into Italy and married the widowed Queen Adelaide, named himself king of the Lombards, and received homage from Berengar of Ivrea, king of Italy (r. 950-52). Otto named his relatives the new leaders of the stem duchies, but this approach did not completely solve the problem of disloyalty. His son Liudolf, duke of Swabia, revolted and welcomed the Magyars into Germany (953). At Lechfeld, near Augsburg in Bavaria, Otto caught up with the Magyars while they were enjoying a razzia and achieved a signal victory in 955. The Magyars ceased living on plunder, and their leaders created a Christian kingdom called Hungary (1000).

Founding of the Holy Roman Empire

The defeat of the Magyars greatly enhanced Otto’s prestige. He marched into Italy again and was crowned emperor (imperator augustus) by Pope John XII in Rome (962), an event that historians count as the founding of the Holy Roman Empire, although the term was not used until much later. The Ottonian state is also considered the first Reich, or German Empire. Otto used the imperial title without attaching it to any territory. He and later emperors thought of themselves as part of a continuous line of emperors that begins with Charlemagne. (Several of these “emperors” were simply local Italian magnates who bullied the pope into crowning them.) Otto deposed John XII for conspiring against him with Berengar, and he named Pope Leo VIII to replace him (963). Berengar was captured and taken to Germany. John was able to reverse the deposition after Otto left, but he died in the arms of his mistress soon afterwards.

Besides founding the German Empire, Otto’s achievements include the creation of the “Ottonian church system,” in which the clergy (the only literate section of the population) assumed the duties of an imperial civil service. He raised the papacy out of the muck of Rome’s local gangster politics, assured that the position was competently filled, and gave it a dignity that allowed it to assume leadership of an international church.

Europe in 1000 CE

Further information:

1000Speculation that the world would end in the year 1000 was confined to a few uneasy French monks.[46] Ordinary clerks used regnal years, i.e. the 4th year of the reign of Robert II (the Pious) of France. The use of the modern “anno domini” system of dating was confined to the Venerable Bede and other chroniclers of universal history.

Western Europe remained less developed compared to the Islamic world, with its vast network of caravan trade, or China, at this time the world’s most populous empire under the Song Dynasty. Constantinople had a population of about 300,000, but Rome had a mere 35,000 and Paris 20,000.[47][48] By contrast, Córdoba, in Islamic Spain, at this time the world’s largest city contained 450,000 inhabitants. The Vikings had a trade network in northern Europe, including a route connecting the Baltic to Constantinople through Russia, as did the Radhanites.

With nearly the entire nation freshly ravaged by the Vikings, England was in a desperate state. The long-suffering English later responded with a massacre of Danish settlers in 1002, leading to a round of reprisals and finally to Danish rule (1013), though England regained independence shortly after. But Christianization made rapid progress and proved itself the long-term solution to the problem of barbarian raiding. The territories of Scandinavia were soon to be fully Christianized Kingdoms: Denmark in the 10th century, Norway in the 11th, and Sweden, the country with the least raiding activity, in the 12th. Kievan Rus, recently converted to Orthodox Christianity, flourished as the largest state in Europe. Iceland and Hungary were both declared Christian about 1000 CE.

In Europe, a formalized institution of marriage was established. The proscribed degree of the degree of consanguinity varied, but the custom made marriages annullable by application to the Pope.[49]North of Italy, where masonry construction was never extinguished, stone construction was replacing timber in important structures. Deforestation of the densely wooded continent was under way. The 10th century marked a return of urban life, with the Italian cities doubling in population. London, abandoned for many centuries, was again England’s main economic centre by 1000. By 1000, Bruges and Ghent held regular trade fairs behind castle walls, a tentative return of economic life to western Europe.

In the culture of Europe, several features surfaced soon after 1000 that mark the end of the Early Middle Ages: the rise of the medieval communes, the reawakening of city life, and the appearance of the burgher class, the founding of the first universities, the rediscovery of Roman law, and the beginnings of vernacular literature.

In 1000, the papacy was firmly under the control of German Emperor Otto III, or “emperor of the world” as he styled himself. But later church reforms enhanced its independence and prestige: the Cluniac movement, the building of the first great Transalpine stone cathedrals and the collation of the mass of accumulated decretals into a formulated canon law.

Middle East

Rise of Islam

Consult particular article for details

The Islamic Prophet Muhammad[50]preaching

Rise of Islam

Arab expansion in the 7th century

- Area I : Muhammad

- Area II : Abu Bakr

- Area III : Omar

- Area IV : Uthman

The 10th-century

Grand Mosque of Cordoba

(

Andalusian city,

Córdoba, Spain)

The site of the Grand Mosque was originally a pagan temple, then a Visigothic Christian church, before the Umayyad Moors at first converted the building into a mosque and then built a new mosque on the site.

The rise of Islam begins around the time Muhammadand his followers took flight, the Hijra, to the city of Medina. Muhammad spent his last ten years in a series of battles to conquer the Arabian region. From 622 to 632, Muhammad as the leader of a Muslim community in Medina was engaged in a state of war with the Meccans. In the proceeding decades, the area of Basra was conquered by the Muslims. During the reign of Umar, the Muslim army found it a suitable place to construct a base. Later the area was settled and a mosque was erected. Madyanwas conquered and settled by Muslims, but the environment was considered harsh and the settlers moved to Kufa. Umar defeated the rebellion of several Arab tribes in a successful campaign, unifying the entire Arabian peninsula and giving it stability. Under Uthman‘s leadership, the empire, through the Muslim conquest of Persia, expanded into Fars in 650, some areas of Khorasan in 651, and the conquest of Armenia was begun in the 640s. In this time, the Islamic empire extended over the whole Sassanid Persian Empire and to more than two-thirds of the Eastern Roman Empire. The First Fitna, or the First Islamic Civil War, lasted for the entirety of Ali ibn Abi Talib‘s reign. After the recorded peace treaty with Hassan ibn Ali and the suppression of early Kharijites‘ disturbances, Muawiyah I acceded to the position of Caliph.

Islamic expansion

The Islamic expansion of the 7th and 8th centuries

-

Muhammad’s conquests, 622–632

-

Rashidun Caliphate, 632–661

-

Umayyad Caliphate, 661–750

The Muslim conquests of the Eastern Roman Empire and Arab wars occurred between 634 and 750. Starting in 633, Muslims conquered Iraq. The Muslim conquest of Syriawould begin in 634 and would be complete by 638. The Muslim conquest of Egypt started in 639. Before the Muslim invasion of Egypt began, the Eastern Roman Empire had already lost the Levant and its Arab ally, the Ghassanid Kingdom, to the Muslims. The Muslims would bring Alexandria under control and the fall of Egypt would be complete by 642. Between 647 and 709, Muslims swept across North Africa and established their authority over that region.

The Transoxiana region was conquered by Qutayba ibn Muslimbetween 706 and 715 and loosely held by the Umayyads from 715 to 738. This conquest was consolidated by Nasr ibn Sayyar between 738 and 740. It was under the Umayyads from 740-748 and under the Abbasids after 748. Sindh, attacked in 664, would be subjugated by 712. Sindh became the easternmost province of the Umayyad. The Umayyad conquest of Hispania (Visigothic Spain) would begin in 711 and end by 718. The Moors, under Al-Samh ibn Malik, swept up the Iberian peninsula and by 719 overran Septimania; the area would fall under their full control in 720. With the Islamic conquest of Persia, the Muslim subjugation of the Caucasus would take place between 711 and 750. The end of the sudden Islamic Caliphate expansion ended around this time. The final Islamic dominion eroded the areas of the Iron Age Roman Empire in the Middle East and controlled strategic areas of the Mediterranean.

At the end of the 8th century, the former Western Roman Empire was decentralized and overwhelmingly rural. The Islamic conquest and rule of Sicily and Malta was a process which started in the 9th century. Islamic rule over Sicily was effective from 902, and the complete rule of the island lasted from 965 until 1061. The Islamic presence on the Italian Peninsula was ephemeral and limited mostly to semi-permanent soldier camps.

Caliphs and empire

The Abbasid Caliphate, ruled by the Abbasid dynasty of caliphs, was the third of the Islamic caliphates. Under the Abbasids, the Islamic Golden Age philosophers, scientists, and engineers of the Islamic world contributed enormously to technology, both by preserving earlier traditions and by adding their own inventions and innovations. Scientific and intellectual achievements blossomed in the period.

The Abbasids built their capital in Baghdad after replacing the Umayyad caliphs from all but the Iberian peninsula. The influence held by Muslim merchants over African-Arabian and Arabian-Asian trade routes was tremendous. As a result, Islamic civilization grew and expanded on the basis of its merchant economy, in contrast to their Christian, Indian, and Chinese peers who built societies from an agricultural landholding nobility.

The Abbasids flourished for two centuries but slowly went into decline with the rise to power of the Turkish army they had created, the Mamluks. Within 150 years of gaining control of Persia, the caliphs were forced to cede power to local dynastic emirs who only nominally acknowledged their authority. After the Abbasids lost their military dominance, the Samanids (or Samanid Empire) rose up in Central Asia. The Sunni Islam empire was a Tajik state and had a Zoroastrian theocratic nobility. It was the next native Persian dynasty after the collapse of the Sassanid Persian empire, caused by the Arab conquest.

European timelines

Beginning years

- Dates

Ending years

- Dates

See also[edit]

References

- Citations

- Jump up^ For more detail on the various starting and ending dates used by historians, see Middle Ages#Terminology and periodisation

- Jump up^ Hopkins, Keith Taxes and Trade in the Roman Empire (200 BC – AD 400)

- ^ Jump up to:a b Berglund, B. E. (2003). “Human impact and climate changes—synchronous events and a causal link?” (PDF). Quaternary International. 105: 7–12. Bibcode:2003QuInt.105….7B. doi:10.1016/S1040-6182(02)00144-1.

- Jump up^ Curry, Andrew, “Fall of Rome Recorded in Trees“, ScienceNOW, 13 January 2011.

- Jump up^ Heather, Peter, 1998, The Goths, pp. 51-93

- Jump up^ Eisenberg, Robert, “The Battle of Adrianople: A Reappraisal“, p. 112.

- Jump up^ Kerrigan, Michael (22 March 2017). “Battle of Adrianople”. Encylopedia Britannica. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- Jump up^ Gibbon, Edward, A History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, 1776.

- Jump up^ Excerpta Valesiana

- Jump up^ McEvedy 1992, op. cit.

- Jump up^ “Scientists Identify Genes Critical to Transmission of Bubonic Plague Archived 2007-10-07 at the Wayback Machine.”, News Release, National Institutes of Health, July 18, 1996.

- Jump up^ The History of the Bubonic Plague Archived 2008-04-15 at the Wayback Machine..

- Jump up^ An Empire’s Epidemic.

- Jump up^ Hopkins DR (2002). The Greatest Killer: Smallpox in history. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-35168-8. Originally published as Princes and Peasants: Smallpox in History (1983), ISBN 0-226-35177-7

- Jump up^ How Smallpox Changed the World, By Heather Whipps, LiveScience, June 23, 2008

- Jump up^ Roman Empire Population

- Jump up^ Storey, Glenn R., “The population of ancient Rome“, Antiquity, December 1, 1997.

- Jump up^ Harbeck, Michaela; Seifert, Lisa; Hänsch, Stephanie; Wagner, David M.; Birdsell, Dawn; Parise, Katy L.; Wiechmann, Ingrid; Grupe, Gisela; Thomas, Astrid; Keim, P; Zöller, L; Bramanti, B; Riehm, JM; Scholz, HC (2013). Besansky, Nora J, ed. “Yersinia pestis DNA from Skeletal Remains from the 6th Century AD Reveals Insights into Justinianic Plague”. PLoS Pathogens. 9 (5): e1003349. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003349. PMC 3642051. PMID 23658525.

- Jump up^ Bos, Kirsten; Stevens, Philip; Nieselt, Kay; Poinar, Hendrik N.; Dewitte, Sharon N.; Krause, Johannes (28 November 2012). Gilbert, M. Thomas P, ed. “Yersinia pestis: New Evidence for an Old Infection”. PLoS ONE. 7 (11): e49803. Bibcode:2012PLoSO…749803B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049803. PMC 3509097. PMID 23209603.

- Jump up^ 6th century mosaic from the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna

- Jump up^ City populations from Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth: An Historical Census Archived February 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. (1987, Edwin Mellon Press) by Tertius Chandler

- Jump up^ http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9239

- Jump up^ Hunter, Shireen (2004). Islam in Russia: The Politics of Identity and Security. Routledge. p. 3. ISBN 978-0765612830.

It is difficult to establish exactly when Islam first appeared in Russia because the lands that Islam penetrated early in its expansion were not part of Russia at the time, but were later incorporated into the expanding Russian Empire. Islam reached the Caucasus region in the middle of the seventh century as part of the Arab conquest of the Iranian Sassanid Empire.

- Jump up^ Kennedy, Hugh (1995). “The Muslims in Europe”. In McKitterick, Rosamund, The New Cambridge Medieval History: c. 500 – c. 700, pp. 249–272. Cambridge University Press. 052136292X.

- Jump up^ Cini Castagnoli, G.C., Bonino, G., Taricco, C. and Bernasconi, S.M. 2002. “Solar radiation variability in the last 1400 years recorded in the carbon isotope ratio of a Mediterranean sea core”, Advances in Space Research 29: 1989-1994.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Cantor, Norman. “The Civilization of the Middle Ages”. p 102

- Jump up^ McKitterick, Rosamond (1995). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 2, C.700-c.900. Cambridge University Press. pp. 87–90. ISBN 9780521362924.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Cantor, Norman. “The Civilization of the Middle Ages”. p 147

- Jump up^ Cantor, Norman. “The Civilization of the Middle Ages”. p 148

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Cantor, Norman. “The Civilization of the Middle Ages”. p 165

- ^ Jump up to:a b Cantor, Norman. “The Civilization of the Middle Ages”. p 189

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Cantor, Norman. “The Civilization of the Middle Ages”. p 170

- Jump up^ Lienhard, John H. “No. 1318: Three-Field Rotation”. Engines of Our Ingenuity. University of Houston.

- Jump up^ Barford, P. M. (2001). The Early Slavs. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Cantor, Norman. “The Civilization of the Middle Ages”. p 52

- Jump up^ “De praescriptione haereticorum, VII”.

- Jump up^ Pierre Riché, Education and Culture in the Barbarian West: From the Jeremy Marcelino II, (Columbia: Univ. of South Carolina Pr., 1976), pp. 100-129.

- Jump up^ Pierre Riché, Education and Culture in the Barbarian West: From the Sixth through the Eighth Century, (Columbia: Univ. of South Carolina Pr., 1976), pp. 307-323.

- Jump up^ William Stahl, Roman Science, (Madison: Univ. of Wisconsin Pr.) 1962, see esp. pp. 120-133.

- Jump up^ Linda E. Voigts, “Anglo-Saxon Plant Remedies and the Anglo-Saxons,” Isis, 70(1979):250-268; reprinted in M. H. Shank, ed., The Scientific Enterprise in Antiquity and the Middle Ages, (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Pr., 2000).

- Jump up^ Stephen C. McCluskey, “Gregory of Tours, Monastic Timekeeping, and Early Christian Attitudes to Astronomy,” Isis, 81(1990):9-22; reprinted in M. H. Shank, ed., The Scientific Enterprise in Antiquity and the Middle Ages, (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Pr., 2000).

- Jump up^ Stephen C. McCluskey, Astronomies and Cultures in Early Medieval Europe, (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1998), pp. 149-57.

- Jump up^ Faith Wallis, “‘Number Mystique’ in Early Medieval Computus Texts,” pp. 179-99 in T. Koetsier and L. Bergmans, eds. Mathematics and the Divine: A Historical Study, (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2005).

- Jump up^ Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books A Living History. United States: Getty Publications. pp. 15, 38–40. ISBN 9781606060834.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Cantor, Norman. “The Civilization of the Middle Ages”. p 153

- Jump up^ Cantor, 1993 Europe in 1050 p 235.

- Jump up^ Pasciuti, Daniel; Chase-Dunn, Christopher (21 May 2002). “Estimating The Population Sizes of Cities”. Urbanization and Empire Formation Project. University of California, Riverside.

- Jump up^ http://sumbur.n-t.org/sg/ua/ddk.htm

- Jump up^ Dowling, Francis (9 May 1903). “Heredity with Especial Reference to Certain Eye Affections”. The Cincinnati Lancet-Clinic. 89: 478.

- Jump up^ 17th-century Ottoman copy of an early 14th-century (Ilkhanate period) manuscript of Northwestern Iran or northern Iraq (the “Edinburgh codex). Illustration of Abū Rayhan al-Biruni ‘s al-Athar al-Baqiyah (الآثار الباقيةة, “The Remaining Signs of Past Centuries”)

Further reading

- Cambridge Economic History of Europe, vol. I 1966. Michael M. Postan, et al., editors.

- Norman F. Cantor, 1963. The Medieval World 300 to 1300, (New York: MacMillen Co.)

- Marcia L. Colish, 1997. Medieval Foundations of the Western Intellectual Tradition: 400-1400. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press)

- Georges Duby, 1974. The Early Growth of the European Economy: Warriors and Peasants from the Seventh to the Twelfth Century(New York: Cornell University Press) Howard B. Clark, translator.

- Georges Duby, editor, 1988. A History of Private Life II: Revelations of the Medieval World (Harvard University Press)

- Heinrich Fichtenau, (1957) 1978. The Carolingian Empire(University of Toronto) Peter Munz, translator.

- Charles Freeman, 2003. The Closing of the Western Mind: The Rise of Faith and the Fall of Reason (London: William Heinemann)

- Richard Hodges, 1982. Dark Age Economics: The Origins of Towns and Trade AD 600-1000 (New York: St Martin’s Press)

- David Knowles, (1962) 1988. The Evolution of Medieval Thought(Random House)

- Richard Krautheimer, 1980. Rome: Profile of a City 312-1308(Princeton University Press)

- Robin Lane Fox, 1986. Pagans and Christians (New York: Knopf)

- David C. Lindberg, 1992. The Beginnings of Western Science: 600 BC-1450 AD (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press)

- John Marenbon (1983) 1988.Early Medieval Philosophy (480-1150): An Introduction (London: Routledge)

- Rosamond McKittrick, 1983 The Frankish Church Under the Carolingians (London: Longmans, Green)

- Karl Frederick Morrison, 1969. Tradition and Authority in the Western Church, 300-1140 (Princeton University Press)

- Pierre Riché, (1978) 1988. Daily Life in the Age of Charlemagne(Liverpool: Liverpool University Press)