Giacobbe Giusti, Diadumenos

Giacobbe Giusti, Diadumenos

The Athens example, with the quiver in view. National Archaeological Museum of Athens

Giacobbe Giusti, Reconstruction, in a patinated cast at the Pushkin Museum, Moscow

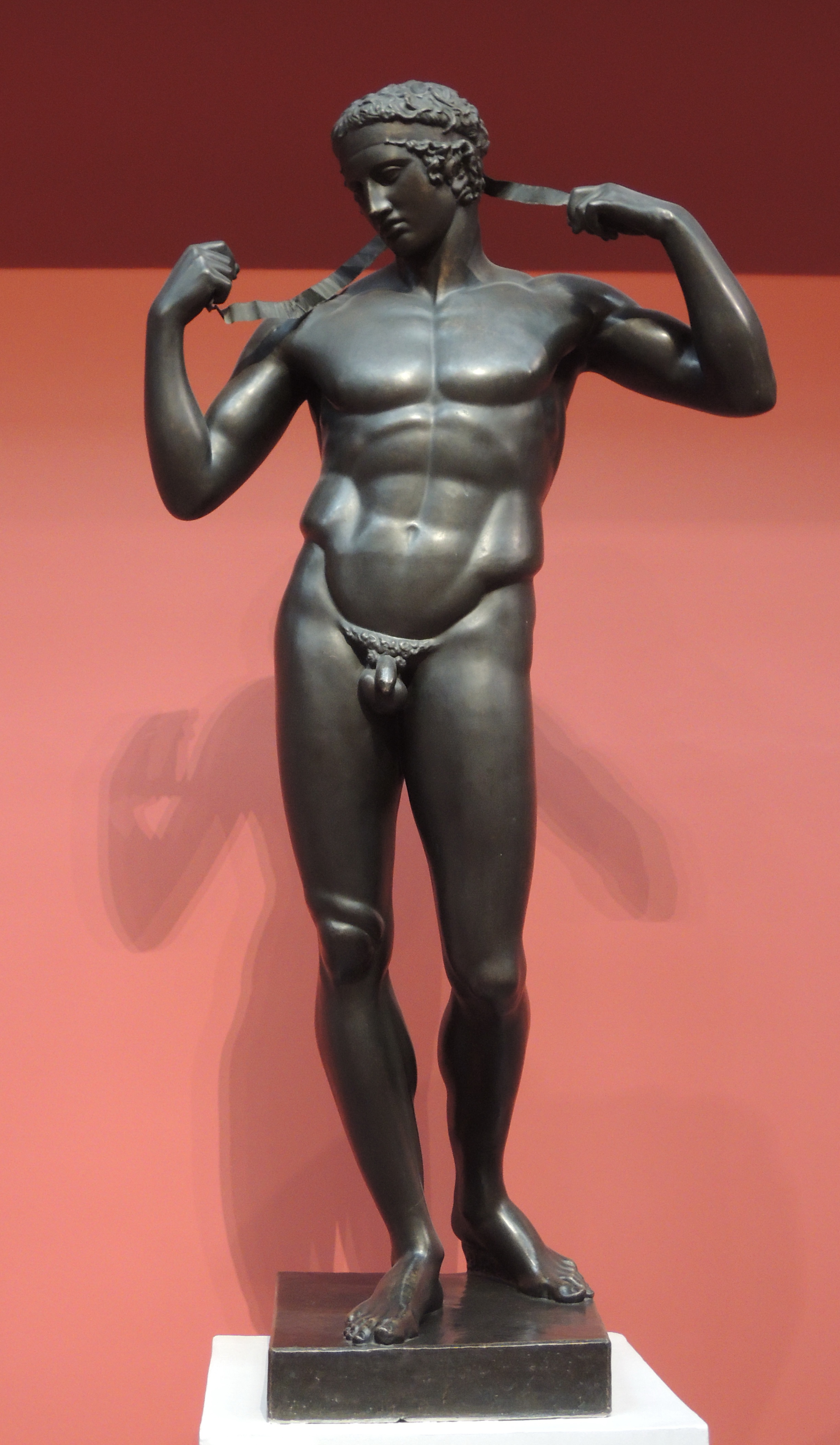

The Diadumenos (“diadem-bearer”), together with the Doryphoros (spear bearer), are two of the most famous figural types of the sculptor Polyclitus, forming a basic pattern of Ancient Greek sculpture that all present strictly idealised representations of young male athletes in a convincingly naturalistic manner.

The Diadumenos is the winner of an athletic contest at a games, still nude after the contest and lifting his arms to knot the diadem, a ribbon-band that identifies the winner and which in the bronze original of about 420 BCE would have been represented by a ribbon of bronze.[1] The figure stands in contrapposto with his weight on his right foot, his left knee slightly bent and his head inclined slightly to the right, self-contained, seeming to be lost in thought. Phidias was credited with a statue of a victor at Olympia in the act of tying the fillet around his head; besides Polyclitus, his successors Lysippos and Scopas also created figures of this kind.

Roman copies

Both Pliny’s Natural History and Lucian‘s Philopseudes[2] described Roman marbles of a Diadumenos copied from Greek originals in bronze, yet it was not recognized until 1878[3] that the Roman marble from Vaison-la-Romaine (Roman Vasio) in the British Museum and two others recreate the lost Polyclitan bronze original.[4] Pliny recorded that the Polyclitan original fetched at auction the extraordinary price of a hundred talents, an enormous sum in Antiquity, as Adolf Furtwängler pointed out.[5] Indeed, Roman marble copies must have abounded, to judge from the number of recognizable fragments and complete works, including a head at the Louvre, a complete example at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, another complete example at the Prado Museum, and another complete example of somewhat different character, the somewhat below lifesize Roman marble Farnese Diadumenos at the British Museum, which preserves the end of the ribband falling from the right hand. Another version in the British Museum, slightly damaged but in otherwise reasonable condition, is from Vaison in France. Freer versions were executed in reduced scale as bronze statuettes,[6] and the head of Diadumenos-type appears on numerous Roman engraved gems.[7]

The marble Diadumenos from Delos at the National Museum, Athens (right) has the winner’s cloak and his quiver laid upon the tree stump, hinting that he is the victor in an archery match, with perhaps an implied reference to Apollo, who was conceived, too, as an idealised youth.

Giacobbe Giusti, Head of the Diadumenos

Modern reception

A mark of the continuing artistic value placed on the Diadumenos type in the modern era, once it had been reconnected with Polyclitus in 1878, may be drawn from the facts that a copy was among the sculptures ranged on the roof of the National Archaeological Museum, Athens, when it was completed in 1889,[8] and that the Esquiline Venus has sometimes been interpreted as a female version of the diadumenos type (a diadumene, or woman tying a diadem).

Giacobbe Giusti, Head of the Diadumenos type

Notes

- Jump up ^ In Hellenistic times the diadem became a symbol of royalty; in the Polyclitan Diadumenos, however, the action is still a simple tying-on of the winner’s headband.

- Jump up ^ Pliny’s Natural History, xxxiv.55f; Philopseudes, 18, praising the Diadoumenos for its beauty

- Jump up ^ Adolf Michaelis, 1878. “Tre statue Policlitee”, Annali dell’Instituto di Corrispondenza Archeologica pp 5-30, noted in Haskell and Penny 1981:118, note 11.

- Jump up ^ The hands have been lost.

- Jump up ^ Furtwängler, Masterpieces of Greek Sculpture: A Series of Essays on the History of Art (Heineman) 1895:245, in a chapter “Diadumenos and Doryphoros” that recreates Polyclitus’ artistic development in confident detail that would no longer be considered possible.

- Jump up ^ For example, the bronze statuette conserved in the Cabinet des médailles of the Bibliothèque nationale

- Jump up ^ The less often seen full figure appears on a plasma gem described and illustrated by Sidney Colvin, “A New Diadumenos Gem”, The Journal of Hellenic Studies 2 (1881:352-353)

- Jump up ^ Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, 1981. Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture 1500-1900 (Yale University Press), p. 107.

References

- Herbert Beck, Peter C. Bol, Maraike Bückling (Hrsg.): Polyklet. Der Bildhauer der griechischen Klassik. Ausstellung im Liebieghaus-Museum Alter Plastik Frankfurt am Main. Von Zabern, Mainz 1990 ISBN 3-8053-1175-3

- Detlev Kreikenbom: Bildwerke nach Polyklet. Kopienkritische Untersuchungen zu den männlichen statuarischen Typen nach polykletischen Vorbildern. “Diskophoros”, Hermes, Doryphoros, Herakles, Diadumenos. Mann, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-7861-1623-7

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diadumenos