Giacobbe Giusti, San Vitale (Ravenna)

Giacobbe Giusti, San Vitale (Ravenna)

Giacobbe Giusti, San Vitale (Ravenna)

Giacobbe Giusti, San Vitale (Ravenna)

Giacobbe Giusti, San Vitale (Ravenna)

Giacobbe Giusti, San Vitale (Ravenna)

Giacobbe Giusti, San Vitale (Ravenna)

Giacobbe Giusti, San Vitale (Ravenna)

Giacobbe Giusti, San Vitale (Ravenna)

Giacobbe Giusti, San Vitale (Ravenna)

Giacobbe Giusti, San Vitale (Ravenna)

Giacobbe Giusti, San Vitale (Ravenna)

Giacobbe Giusti, San Vitale (Ravenna)

Exteriors

Interiors

Cupola

Mosaics

Drawings

Die Kirche San Vitale in Ravenna, vermutlich 537 begonnen und 547 dem heiligen Vitalis geweiht, zählt zu den bedeutendsten Kirchenbauten der spätantik–frühbyzantinischen Zeit. In ihr verbinden sich Architekturformen aus dem Oströmischen Reich mit für das damalige Italien typischen Bautechniken. Sie entstand in einer Zeit des Umbruchs, als der oströmische Kaiser Justinian I. Krieg gegen das ostgotische Königreich in Italien führte. Berühmt ist die als Zentralbau errichtete Kirche vor allem für ihre Mosaikausstattung im Innern, insbesondere die Porträts von Justinian und seiner Frau Theodora im unteren Apsisgewände. Mit den anderen frühen Kirchenbauten in Ravenna gehört San Vitale seit 1996 zum UNESCO-Welterbe. 1960 erhielt sie durch Papst Johannes XXIII. den Ehrentitel Basilica minor.

Baugeschichte

Giacobbe Giusti, San Vitale (Ravenna)

An der Stelle der heutigen Kirche befand sich im 5. Jahrhundert n. Chr. bereits ein kleiner kreuzförmiger Bau, wie Grabungen aus dem Jahr 1911 nachgewiesen haben. Ob dieser bereits der Verehrung des Heiligen Vitalis diente, lässt sich nicht nachweisen. Nach Keller gilt der Narthex des heutigen Gebäudes als Ort des Martyriums des Heiligen.[1]

Der ravennatische Chronist Agnellusberichtet im 9. Jahrhundert, dass der katholische Bischof Ecclesius, der sein Amt von 521 bis 532 innehatte, der Begründer des heute zu sehenden Baus gewesen sei. Dies wird bestätigt, durch ein Mosaik in der Apsis der Kirche, welches Ecclesius als Stifter des Baus präsentiert. Zum damaligen Zeitpunkt war Ravenna noch Hauptstadt des ostgotischen Königreiches, dessen germanische Elite sich zum arianischen Christentum bekannte. Die Bevölkerung Ravennas war dementsprechend in eine arianische und eine katholische Gemeinde gespalten, an deren Spitze jeweils ein eigener Bischof stand. Agnellus berichtet weiterhin, dass ein Bankier namens Julianus Argentarius den Bau finanziert habe. Auch hierfür lassen sich Nachweise im Kircheninneren finden, wo mehrmals das Monogramm des Julianus auftaucht. Sein Name fällt auch im Zusammenhang mit der Finanzierung anderer Kirchen in Ravenna, wie z. B. Sant’Apollinare in Classe. Die Rolle von Ecclesius’ Nachfolger Ursicinus (534-536) beim Bau von San Vitale ist unbekannt. Die eigentlichen Bauarbeiten wurden wahrscheinlich erst unter dem nächsten Bischof, Victor (537/38-544/45), begonnen. Es ist sein Monogramm, welches die Kämpferblöcke im Kircheninneren tragen. In die Zeit seines Episkopats fiel auch das Ende der ostgotischen Herrschaft über Ravenna, als die Stadt 540 durch byzantinische Truppen unter Befehl des Feldherrn Belisareingenommen wurde. Die Weihung der Kirche fand laut Agnellus schließlich im Jahr 547 unter Bischof Maximian (546-556) statt. Sein Porträt findet sich auf einem Mosaik im unteren Apsisgewände.

Im 10. Jahrhundert gelangte San Vitale in den Besitz einer Benediktinergemeinde. Während des Mittelalters wurden einige Veränderungen am Bau vorgenommen. So wurden beispielsweise in die Decken des Umgangs und der Empore Kreuzgratgewölbeeingefügt. Um deren Schub abzufangen wurden am Außenbau mehrere Strebepfeiler angefügt. Im 16. Jahrhundert erhielt die Kirche ein neues Eingangsportal im Osten.

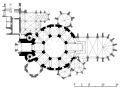

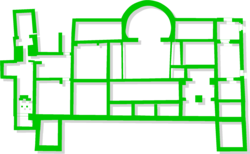

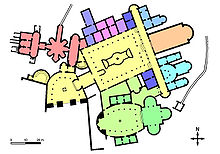

Architektur

San Vitale wurde als zweischaliger Nischenzentralbau mit eingestelltem Stützenkranz entworfen. Den Kern des Gebäudes bildet ein oktogonaler, überkuppelter Zentralraum. Den Haupteingang dazu stellte ursprünglich der im Südwesten angeschlossene Narthex dar. Dieser ist aus der Achse des Gebäudes nach Südosten hin verschoben, so dass er nur an einer Kante an das Oktogon anstößt. Von den beiden Apsiden, mit denen der Narthex ursprünglich abschloss, ist heute nur noch die nördliche erhalten. Den Übergang zwischen Narthex und Oktogon bilden zwei Zwickelräume, die von je einem Treppenturm (ø: 5,40 m).[2] flankiert werden, über welche man die Emporen erreicht.

Der Kern des Zentralraums wird durch acht Pfeiler, welche die Kuppel tragen, ebenfalls als Oktogon definiert. Den Raum zwischen den Pfeilern füllen durch zweisäulige Arkaden gegliederte, halbrunde Nischen, welche sich auch in den Emporen fortsetzen. Die Kuppel, mit einem Durchmesser von 15,70 m[3], ruht auf einem achteckigen, durchfensterten Tambour, wurde in der für Italien typischen Leichtbauweise aus Ringen von Tonröhren, den sogenannten tubi fittili, errichtet[4] und nach außen mit Pyramidendach überdeckt. Die Dekoration der Kuppel stammt aus dem späten 18. Jahrhundert. Dieser zentrale Raumteil ist von einem etwas niedrigeren, doppelgeschossigen Umgang umgeben.

Der Altarraum ist durch Arkaden aus dem Umgang herausgetrennt und von einem Kreuzgratgewölbe überdeckt. An ihn schließt sich im Nordosten die polygonal ummantelte Apsis an. Diese wird flankiert von zwei Kapellen mit kreisrundem Grundriss. Im Altarraum und in der Apsis befinden sich auch die spätantiken Mosaiken, für die San Vitale bekannt ist.

Die gesamte Kirche ist aus massivem Ziegelwerk gemauert. Die langen, schmalen Ziegel, die dabei verwendet wurden, gleichen denen der anderen Bauten des Julianus Argentarius und sind leicht von den Ziegeln zu unterscheiden, die beispielsweise bei Bauten der Galla Placidia oder des Theoderich Verwendung fanden.

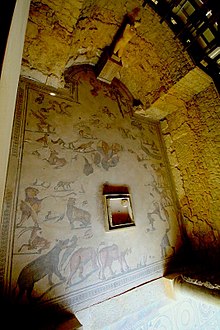

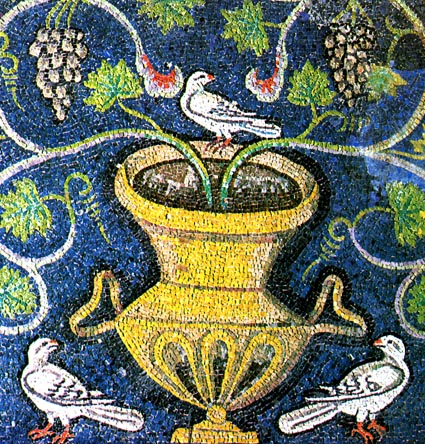

Mosaiken

Bekannt ist San Vitale, wie viele der spätantiken Monumente Ravennas, für seine reiche Mosaikausstattung. Diese teilt sich in Wand- und Bodenmosaiken auf. Letztere breiteten sich ursprünglich als verschiedenartige ornamentale und florale Muster über den gesamten Kirchenraum aus und sind eher in matten Erdtönen gehalten. Während sie im Umgang noch größtenteils erhalten sind, wurden sie im zentralen Kuppelraum mittlerweile weitgehend durch einen jüngeren Opus sectile-Boden ersetzt.

Einen deutlich anderen Eindruck machen die ebenfalls noch in der Entstehungszeit der Kirche gefertigten Wand- und Deckenmosaiken. Sie überziehen nahezu den gesamten Altar- und Apsisbereich und beeindrucken durch ihre kräftigen Farben, wobei Blau, Grün und Gold als Hintergrundfarben dominieren. Verglichen mit Mosaiken der klassischen Antike sind die Darstellungen aus relativ großen Tesseraezusammengesetzt, wobei das Inkarnat feiner modelliert wurde als der Hintergrund. Auch dies beruht auf der in der Spätantike aufgekommenen Darstellungskonvention, nach der der Inhalt Vorrang vor der Form hat. Der überwältigende Eindruck der Mosaiken beruht vor allem auf ihrer Farbenpracht. Im Gegensatz zu anderen Darstellungen, die über die Jahrhunderte häufig an Farbintensität verloren, bestehen die Mosaiken aus farbechten (Halbedel-)Steinen. Bei den goldenen Tesserae wurde echtes Blattgold verwendet, das zwischen zwei Lagen Glas eingebettet wurde.

Bereits der Eingangsbereich zum Altarraum, die Laibung des Triumphbogens ist vollständig mit Mosaiken überzogen. Sie zeigen Bildnismedaillons von Christus, seinen zwölf Aposteln und der Heiligen Gervasius und Protasius, die ursprünglich auch in einer der beiden Seitenkapellen der Kirche verehrt wurden und als Söhne der Heiligen Vitalis galten. Die meisten figürlichen Darstellungen auf den Mosaiken des Altarraums beziehen sich auf das Alte Testament. Die beiden Lunetten oberhalb der Säulenstellungen nördlich und südlich des Altars zeigen im Norden Abraham beim Bewirten der drei Pilger sowie bei der Opferung seines Sohnes Isaak und im Norden Abel und Melchisedek bei der Darbringung von Opfern für Gott. Beide Mosaiken beziehen sich deutlich auf die Eucharistie, die unterhalb von ihnen am Altar der Kirche gefeiert wurde. Oberhalb der Lunetten befinden sich neben je einem paar Engel Darstellungen aus dem Leben Mose sowie der Propheten Jeremia und Jesaja. Darüber schließen sich neben den Fensteröffnungen in die Emporen Ganzkörperporträts der vier Evangelisten mit ihren jeweiligen Symboltieren an. Die oberste Zone ist von floralen Mustern überzogen, während die Decke ein von vier Engeln getragenes Medaillon mit dem Lamm Gottes zeigt. Die Apsisstirnwand trägt neben einem weiteren Paar Engel Darstellungen der himmlischen Städte Jerusalem und Betlehem.

Die Apsis wird dominiert durch den in der Apsiskalotte auf einer Himmelskugel thronenden, bartlosen Christus. Die Darstellung auf der “Himmelskugel”, mit der das gesamte Weltall gemeint ist, ist eine künstlerische Umsetzung des Ehrennamens “Kosmokrator” (Weltenherrscher). Ihm werden von zwei Engeln der Titelheilige Vitalis, dem Christus eine Märtyrerkrone überreicht, und der als Stifter der Kirche dargestellte Bischof Ecclesius zugeführt.

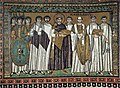

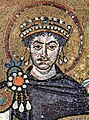

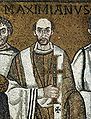

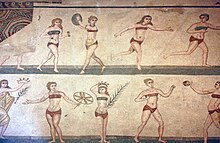

Die berühmtesten Mosaiken von San Vitale dürften allerdings die im Apsisgewände befindlichen Porträts von Justinian und Theodora in Begleitung ihres Hofstaates sein. Justinian im Norden steht im Zentrum seines Mosaikfeldes und trägt eine Patene (Hostienschale) in Richtung des in der Apsiskalotte dargestellten Christus. Er ist durch seine aufwändige Tracht deutlich von den umgebenden Personen abgehoben und als Kaiser gekennzeichnet: er trägt ein dreireihiges edelsteinbesetztes Diadem und ein purpurnes Paludamentum mit einer goldbesetzten Tabula, einem rechteckigen Stück Stoff, das hohe Würdenträger am spätrömischen Hof auszeichnete und in ähnlicher Form auch bei anderen Personen der beiden Mosaiken zu erkennen ist. Beachtenswert ist auch die prunkvolle Scheibenfibel (Orbiculus) mit Pendilien und Trifolium (dreiteiliges Schmuckstück). Ein weiteres Zeichen seiner kaiserlichen Würde ist der Nimbus, der seinen Kopf umgibt. Dem Kaiser folgen einige Würdenträger und seine Leibgarde. Justinian voran geht der Bischof Ravennas, der durch eine Inschrift als Maximian benannt ist, sowie zwei weitere Geistliche. Maximian trägt eine Alba (weiße Tunika, bzw. Dalmatik), darüber eine Planeta und ein Pallium als erzbischöfliches Abzeichen. Alle Männer tragen spezielle Calcei, Sandalen mit Kappen an Zehen und Ferse, die nur von der Oberschicht getragen wurden. Der Fachbegriff für die roten kaiserlichen Sandalen ist Calcei mullei.[5]

Im südlichen Mosaikfeld ist Theodora aus dem Zentrum etwas nach Osten verschoben. Sie ist durch ihre Tracht, sowie durch ihren Nimbus und die sie hinterfangende Nische deutlich als Kaiserin gekennzeichnet. Sie trägt eine Dalmatik unter einem purpurnen Umhang, eine Haubenkrone mit langen Pendilien und einen Juwelenkragen. In ihren Händen trägt sie den eucharistischen Weinkelch (Calix). Ihr voran gehen zwei Würdenträger, die denen des gegenüberliegenden Mosaiks ähneln, während ihr eine Gruppe Hofdamen folgt. Außer dem Kaiserpaar und dem Bischof lässt sich keine der dargestellten Personen mit absoluter Sicherheit identifizieren, auch wenn in der Forschung immer wieder Zuschreibungen einiger Figuren beispielsweise als Belisar[6] oder als Mutter Iustinians[7] auftauchen. Die Bedeutung dieser Mosaiken beruht u.a. darauf, dass sie eine der wenigen eindeutig zuschreibbaren Darstellungen des Kaiserpaares darstellen. Besonders die Gesichtszüge scheinen individuellen Charakter zu besitzen, wobei die spätantike Tendenz zum Abstrahieren durchaus noch gut zu erkennen ist. Was die Körpergröße angeht, so ist davon auszugehen, dass sie eher den gesellschaftlichen Rang der Personen abbildet, wie seit der Spätantike allgemein üblich. Darüber hinaus bieten die beiden Mosaiken wertvolle Informationen über die frühbyzantinische Hoftracht.

Es kann als gesichert gelten, dass die Mosaiken der Apsis noch aus der Zeit Bischof Victors (537/38-544/45) stammen. Die Darstellungen des Kaiserpaars können aufgrund der damaligen politischen Situation erst nach der Eroberung Ravennas durch die Byzantiner im Jahr 540 entstanden sein. Victors Nachfolger Maximian ließ die Mosaikausstattung des Altarbereichs vollenden und sein eigenes Porträt anstelle dessen seines Vorgängers in das Mosaikfeld mit dem Bildnis des Kaisers einfügen. Auch das Bildnis des zwischen bzw. hinter Justinian und dem Bischof stehenden Beamten entstand erst in dieser Zeit.[8]

-

Abel und Melchisedek

Fresken

Während die Ausgestaltung des Altar- und Apsisbereichs noch auf die Entstehungszeit San Vitales zurückgeht, entstand der heute zu sehende Bildschmuck des zentralen Kuppelraums erst in der Neuzeit. Gegen Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts beauftragten die Benediktiner-Mönche den Künstler Serafino Barozzi mit der Ausschmückung der ihnen anvertrauten Kirche. Diesem schloss sich bald darauf Jacopo Guarana an. Vollendet wurde das Werk von Ubaldo Gandolfo, der bereits zuvor mit Barozzi zusammengearbeitet hatte. Bei den Fresken handelt es sich um zeittypische illusionistische Malerei. Im Kuppelscheitel werden der Heilige Vitalis und der Heilige Benedikt im Himmel gezeigt.

Orgel

Die Orgel wurde 1967 von der Orgelbaufirma Mascioni erbaut. Das Instrument hat 53 Register auf drei Manualen und Pedal. Davon sind 15 Register Transmissionen, und 13 Register Extensionen.

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Koppeln: I/II, III/I, III/II, I/P, II/P, III/P; Superoktavkoppeln (II/II, III/II, III/III, I/P, II/P, II/P) und Suboktavkoppel III/II.

Einordnung

Der Bau, der architektonisch am nächsten mit San Vitale verwandt ist, ist die von Justinian I. vor 536 in Konstantinopel errichtete Sergios und Bakchos Kirche. Auch hier bildet ein überkuppelter oktogonalerZentralraum den Mittelpunkt des Gebäudes. Zwischen den Pfeilern wechseln sich allerdings anders als in Ravenna halbrunde und rechteckige Nischen ab. Der Umgang ist wie in San Vitale ebenfalls oktogonal und, für Konstantinopel typisch, mit einer Empore versehen. Diese Innenraumgliederung wirkt sich hier allerdings nicht auf den Außenbau aus, der eine quadratische Grundform hat. Insgesamt steht San Vitale sehr stark – stärker als jede andere ravennatische Kirche – in der konstantinopolitanischen Bautradition. Möglicherweise brachte Bischof Ecclesius die Pläne für den Bau der Kirche mit nach Ravenna, nachdem er 525 gemeinsam mit Papst Johannes I. im Auftrag des ostgotischen Königs Theoderich in die oströmische Hauptstadt gereist war.

Für die westeuropäische Architektur erhielt San Vitale wiederum selbst Vorbildcharakter. Die um 800 von Karl dem Großen erbaute Aachener Pfalzkapelle weist starke Bezüge zu dem ravennatischen Bau auf. Der Frankenherrscher hatte durch seine Eroberung des Langobardenreiches auch Ravenna unter seine Kontrolle gebracht. Der Überlieferung zufolge ließ er Baumaterial, wie z. B. Säulen, von dort nach Aachen schaffen. Karl versuchte wohl seinem eigenen, erst kürzlich errungenen Kaisertum durch solche Rückbezüge auf spätrömisch-byzantinische Traditionen, Legitimität zu verleihen.

Siehe auch

Literatur

- Irina Andreescu-Treadgold, Warren Treadgold: Procopius and the Imperial Panels of S. Vitale. In: The Art Bulletin. Bd. 79, Nr. 4, 1997, S. 708–723, doi:10.1080/00043079.1997.10786808.

- Friedrich Wilhelm Deichmann: Ravenna. Hauptstadt des spätantiken Abendlandes. Band 1: Geschichte und Monumente.Steiner, Wiesbaden 1969, S. 226–256.

- Friedrich Wilhelm Deichmann: Ravenna. Hauptstadt des spätantiken Abendlandes. Band 2: Kommentar. Teil 2. Steiner, Wiesbaden 1976, ISBN 3-515-02005-5, S. 47–206.

- Gianfranco Malafarina (Hrsg.): La Basilica di San Vitale a Ravenna(= Mirabilia Italiae. Guide. 6). Panini, Modena 2006, ISBN 88-8290-909-3 (italienisch und englisch mit zahlreichen Abbildungen).

- Otto G. von Simson: Sacred Fortress. Byzantine Art and Statecraft in Ravenna. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1987, ISBN 0-691-04038-9, S. 23–39.

- Jutta Dresken-Weiland: Die frühchristlichen Mosaiken von Ravenna – Bild und Bedeutung, Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg 2016, ISBN 978-3-7954-3024-5

Weblinks

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/San_Vitale