Giacobbe Giusti, Chariot racing

Giacobbe Giusti, Chariot racing

The Charioteer of Delphi, one of the most famous statues surviving from Ancient Greece

Giacobbe Giusti, Chariot racing

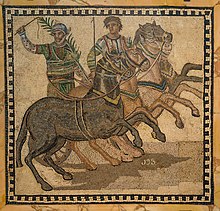

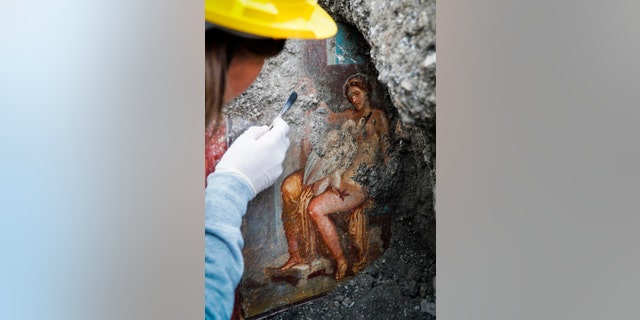

A white charioteer; part of a mosaicof the third century AD, showing four leading charioteers from the different colors, all in their distinctive gear

Giacobbe Giusti, Chariot racing

The Triumphal Quadriga is a set of Roman or Greek bronze statues of four horses, originally part of a monument depicting a quadriga. They date from late Classical Antiquity and were long displayed at the Hippodrome of Constantinople. In 1204 AD, DogeEnrico Dandolo sent them to Venice as part of the loot sacked from Constantinople in the Fourth Crusade.

Giacobbe Giusti, Chariot racing

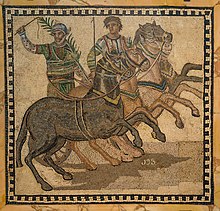

A winner of a Roman chariot race, from the Red team

Giacobbe Giusti, Chariot racing

A modern recreation of chariot racing in Puy du Fou

Chariot racing (Greek: ἁρματοδρομία, translit. harmatodromia, Latin: ludi circenses) was one of the most popular Iranian, ancient Greek, Roman, and Byzantinesports. Chariot racing was dangerous to both drivers and horses as they often suffered serious injury and even death, but these dangers added to the excitement and interest for spectators. Chariot races could be watched by women, who were banned from watching many other sports. In the Roman form of chariot racing, teams represented different groups of financial backers and sometimes competed for the services of particularly skilled drivers. As in modern sports like football, spectators generally chose to support a single team, identifying themselves strongly with its fortunes, and violence sometimes broke out between rival factions. The rivalries were sometimes politicized, when teams became associated with competing social or religious ideas. This helps explain why Roman and later Byzantine emperorstook control of the teams and appointed many officials to oversee them.

The sport faded in importance in the West after the fall of Rome. It survived for a time in the Byzantine Empire, where the traditional Roman factions continued to play a prominent role for several centuries, gaining influence in political matters. Their rivalry culminated in the Nika riots, which marked the gradual decline of the sport.

Early chariot racing

It is unknown exactly when chariot racing began, but It may have been as old as chariots themselves. It is known from artistic evidence on pottery that the sport existed in the Mycenaean world,[a] but the first literary reference to a chariot race is one described by Homer, at the funeral games of Patroclus.[1] The participants in this race were Diomedes, Eumelus, Antilochus, Menelaus, and Meriones. The race, which was one lap around the stump of a tree, was won by Diomedes, who received a slave woman and a cauldron as his prize. A chariot race also was said to be the event that founded the Olympic Games; according to one legend, mentioned by Pindar, King Oenomauschallenged suitors for his daughter Hippodamia to a race, but was defeated by Pelops, who founded the Games in honour of his victory.[2]

Olympic Games

In the ancient Olympic Games, as well as the other Panhellenic Games, there were both four-horse (tethrippon, Greek: τέθριππον) and two-horse (synoris, Greek: συνωρὶς) chariot races, which were essentially the same aside from the number of horses. [b]The chariot racing event was first added to the Olympics in 680 BC with the games expanding from a one-day to a two-day event to accommodate the new event (but was not, in reality, the founding event). The chariot race was not so prestigious as the foot race of 195 meters (stadion, Greek: στάδιον), but it was more important than other equestrian events such as racing on horseback, which were dropped from the Olympic Games very early on.

The races themselves were held in the hippodrome, which held both chariot races and riding races. The single horse race was known as the “keles” (keles, Greek: κέλης).[c] The hippodrome was situated at the south-east corner of the sanctuary of Olympia, on the large flat area south of the stadium and ran almost parallel to the latter. Until recently, its exact location was unknown, since it is buried by several meters of sedimentary material from the Alfeios River. In 2008, however, Annie Muller and staff of the German Archeological Institute used radar to locate a large, rectangular structure similar to Pausanias’s description. Pausanias, who visited Olympia in the second century AD, describes the monument as a large, elongated, flat space, approximately 780 meters long and 320 meters wide (four stadia long and one stadefour plethra wide). The elongated racecourse was divided longitudinally into two tracks by a stone or wooden barrier, the embolon. All the horses or chariots ran on one track toward the east, then turned around the embolon and headed back west. Distances varied according to the event. The racecourse was surrounded by natural (to the north) and artificial (to the south and east) banks for the spectators; a special place was reserved for the judges on the west side of the north bank.[7]

The race was begun by a procession into the hippodrome, while a herald announced the names of the drivers and owners. The tethrippon consisted of twelve laps around the hippodrome, with sharp turns around the posts at either end. Various mechanical devices were used, including the starting gates (hyspleges, Greek: ὕσπληγγες; singular: hysplex, Greek: ὕσπληγξ) which were lowered to start the race. According to Pausanias, these were invented by the architect Cleoitas, and staggered so that the chariots on the outside began the race earlier than those on the inside. The race did not begin properly until the final gate was opened, at which point each chariot would be more or less lined up alongside each other, although the ones that had started on the outside would have been traveling faster than the ones in the middle. Other mechanical devices known as the “eagle” and the “dolphin” were raised to signify that the race had begun, and were lowered as the race went on to signify the number of laps remaining. These were probably bronze carvings of those animals, set up on posts at the starting line.[11]

In most cases, the owner and the driver of the chariot were different persons. In 416 BC, the Athenian general Alcibiades had seven chariots in the race, and came in first, second, and fourth; obviously, he could not have been racing all seven chariots himself.[12] Philip II of Macedon also won an Olympic chariot race in an attempt to prove he was not a barbarian, although if he had driven the chariot himself he would likely have been considered even lower than a barbarian. The poet Pindar did praise the courage of Herodotes of Thebes, however, for driving his own chariot.[13] This rule also meant that women could win the race through ownership, despite the fact that women were not allowed to participate in or even watch the Games. This happened rarely, but a notable example is the Spartan Cynisca, daughter of Archidamus II, who won the chariot race twice. Chariot racing was a way for Greeks to demonstrate their prosperity at the games. The case of Alcibiades indicates also that chariot racing was an alternative route to public exposure and fame for the wealthy.

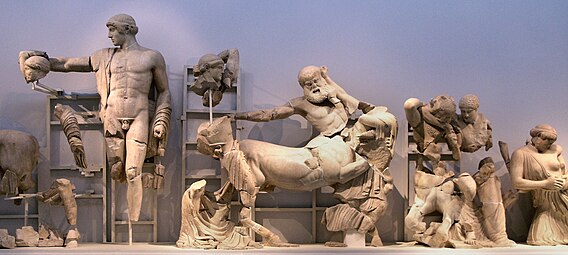

The charioteer was usually either a family member of the owner of the chariot or, in most cases, a slave or a hired professional. Driving a racing chariot required unusual strength, skill, and courage. Yet, we know the names of very few charioteers,[16] and victory songs and statues regularly contrive to leave them out of account. Unlike the other Olympic events, charioteers did not perform in the nude, probably for safety reasons because of the dust kicked up by the horses and chariots, and the likelihood of bloody crashes. Racers wore a sleeved garment called a xystis. It fell to the ankles and was fastened high at the waist with a plain belt. Two straps that crossed high at the upper back prevented the xystis from “ballooning” during the race.

The chariots themselves were modified war chariots, essentially wooden carts with two wheels and an open back, although chariots were by this time no longer used in battle. The charioteer’s feet were held in place, but the cart rested on the axle, so the ride was bumpy. The most exciting part of the chariot race, at least for the spectators, was the turns at the ends of the hippodrome. These turns were very dangerous and often deadly. If a chariot had not already been knocked over by an opponent before the turn, it might be overturned or crushed (along with the horses and driver) by the other chariots as they went around the post. Deliberately running into an opponent to cause him to crash was technically illegal, but nothing could be done about it (at Patroclus’ funeral games, Antilochus in fact causes Menelaus to crash in this way,) and crashes were likely to happen by accident anyway.

Other festivals

As a result of the rise of the Greek cities of the classic period, other great festivals emerged in Asia Minor, Magna Graecia, and the mainland providing the opportunity for athletes to gain fame and riches. Apart from the Olympics, the best respected were the Isthmian Games in Corinth, the Nemean Games, the Pythian Games in Delphi, and the Panathenaic Games in Athens, where the winner of the four-horse chariot race was given 140 amphorae of olive oil (much sought after and precious in ancient times). Prizes at other competitions included corn in Eleusis, bronze shields in Argos, and silver vessels in Marathon.[d] Another form of chariot racing at the Panathenaic Games was known as the apobatai, in which the contestant wore armor and periodically leapt off a moving chariot and ran alongside it before leaping back on again. In these races, there was a second charioteer (a “rein-holder”) while the apobates jumped out; in the catalogues with the winners both the names of the apobates and of the rein-holder are mentioned. Images of this contest show warriors, armed with helmets and shields, perched on the back of their racing chariots. Some scholars believe that the event preserved traditions of Homeric warfare.

Roman era

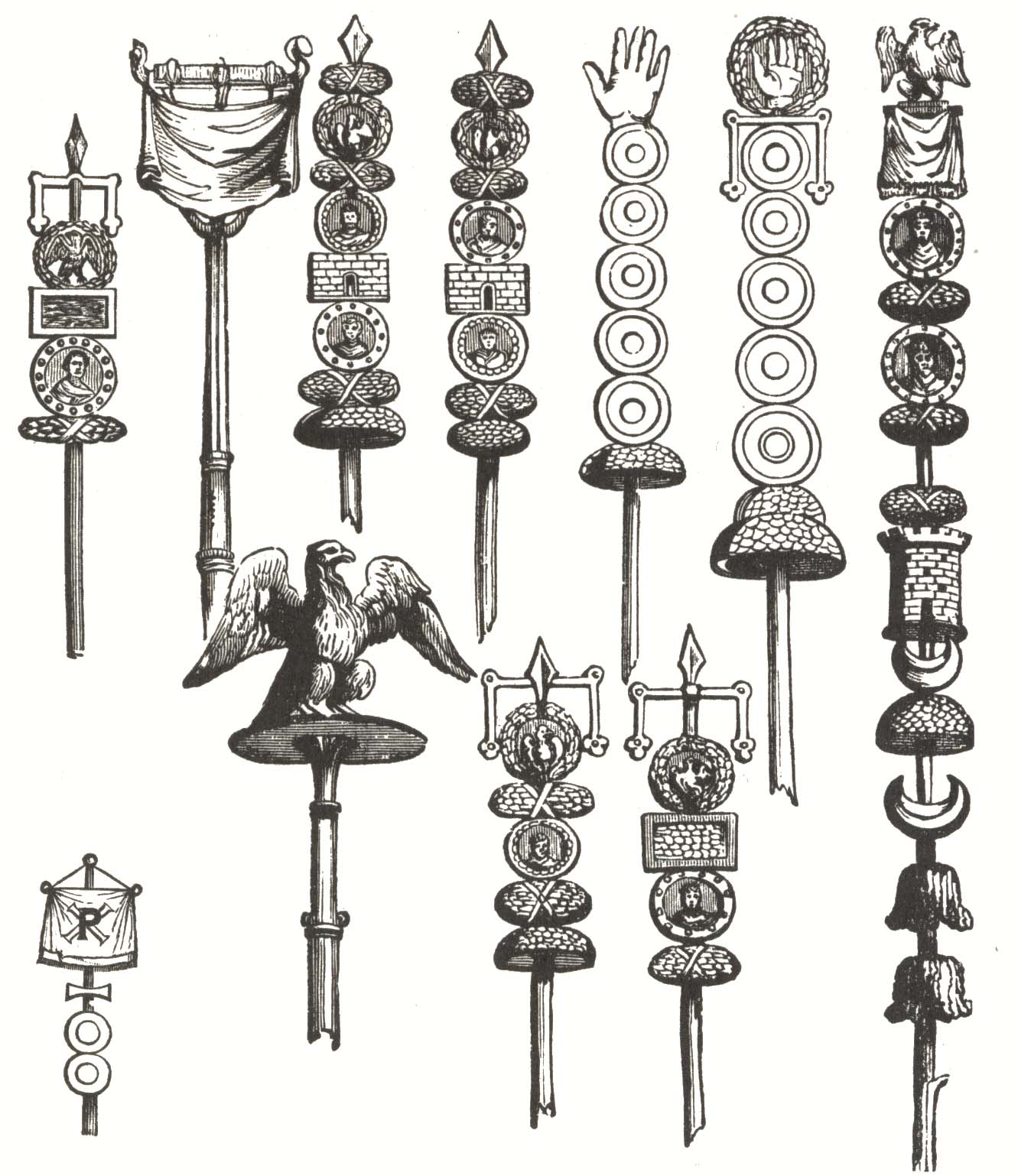

The Romans probably borrowed chariot racing from the Etruscans as well as the racing tracks, who themselves borrowed it from the Greeks, but the Romans were also influenced directly by the Greeks.[e] According to Roman legend, chariot racing was used by Romulus just after he founded Rome in 753 BC as a way of distracting the Sabinemen. Romulus sent out invitations to the neighbouring towns to celebrate the festival of the Consualia, which included both horse races and chariot races. Whilst the Sabines were enjoying the spectacle, Romulus and his men seized and carried off the Sabine women, who became wives of the Romans. Chariot races were a part of several Roman religious festivals, and on these occasions were preceded by a parade (pompa circensis) that featured the charioteers, music, costumed dancers, and images of the gods. While the entertainment value of chariot races tended to overshadow any sacred purpose, in late antiquity the Church Fathers still saw them as a traditional “pagan” practice, and advised Christians not to participate.

Depiction of a chariot race in the Roman era

In ancient Rome, chariot races commonly took place in a circus. The main centre of chariot racing was the Circus Maximus in the valley between Palatine Hill and Aventine Hill,[f] which could seat 250,000 people. It was the earliest circus in the city of Rome. The Circus supposedly dated to the city’s earliest times,[g] but Julius Caesar rebuilt it around 50 BC to a length and width of about 650 metres (2,130 ft) and 125 metres (410 ft), respectively. One end of the track was more open than the other, as this was where the chariots lined up to begin the race. The Romans used a series of gates known as carceres, equivalent to the Greek hysplex. These were staggered like the hysplex, but in a slightly different manner since the center of Roman racing tracks also included medians (the spinae). The carceres took up the angled end of the track, where — before a race — the chariots were loaded behind spring-loaded gates. Typically, when the chariots were ready the emperor (or whoever was hosting the races, if outside of Rome) dropped a cloth known as a mappa, signalling the beginning of the race. The gates would spring open at the same time, allowing a fair start for all participants.

Once the race had begun, the chariots could move in front of each other in an attempt to cause their opponents to crash into the spinae (singular spina). On the top of the spinae stood small tables or frames supported on pillars, and also small pieces of marble in the shape of eggs or dolphins. The spinaeventually became very elaborate, with statues and obelisks and other forms of art, but the addition of these multiple adornments had one unfortunate result: they obstructed the view of spectators on lower seats. At either end of the spina was a meta, or turning point, consisting of large gilded columns.[37] Spectacular crashes in which the chariot was destroyed and the charioteer and horses incapacitated were called naufragia, a Latin word that also means “shipwreck”.

A white charioteer; part of a mosaicof the third century AD, showing four leading charioteers from the different colors, all in their distinctive gear

The race itself was much like its Greek counterpart, although there were usually 24 races every day that, during the fourth century, took place on 66 days each year. However, a race consisted of only 7 laps (and later 5 laps, so that there could be even more races per day), instead of the 12 laps of the Greek race. The Roman style was also more money-oriented; racers were professionals and there was widespread betting among spectators. There were four-horse chariots (quadrigae) and two-horse chariots (bigae), but the four-horse races were more important. In rare cases, if a driver wanted to show off his skill, he could use up to 10 horses, although this was extremely impractical.

The technique and clothing of Roman charioteers differed significantly from those used by the Greeks. Roman drivers wrapped the reins round their waist, while the Greeks held the reins in their hands.[h]Because of this, the Romans could not let go of the reins in a crash, so they would be dragged around the circus until they were killed or they freed themselves. In order to cut the reins and keep from being dragged in case of accident, they carried a falx, a curved knife. They also wore helmets and other protective gear. In any given race, there might be a number of teams put up by each faction, who would cooperate to maximize their chances of victory by ganging up on opponents, forcing them out of the preferred inside track or making them lose concentration and expose themselves to accident and injury. Spectators could also play a part as there is evidence they threw lead “curse” amulets studded with nails at teams opposing their favourite.

A winner of a Roman chariot race, from the Red team

Another important difference was that the charioteers themselves, the aurigae, were considered to be the winners, although they were usually also slaves (as in the Greek world). They received a wreath of laurel leaves, and probably some money; if they won enough races they could buy their freedom. Drivers could become celebrities throughout the Empire simply by surviving, as the life expectancy of a charioteer was not very high. One such celebrity driver was Scorpus, who won over 2000 racesbefore being killed in a collision at the meta when he was about 27 years old. The most famous of all was Gaius Appuleius Diocles who won 1,462 out of 4,257 races. When Diocles retired at the age of 42 after a 24-year career his winnings reportedly totalled 35,863,120 sesterces ($US 15 billion), making him the highest paid sports star in history. The horses, too, could become celebrities, but their life expectancy was also low. The Romans kept detailed statistics of the names, breeds, and pedigrees of famous horses.

Seats in the Circus were free for the poor, who by the time of the Empire had little else to do, as they were no longer involved in political or military affairs as they had been in the Republic. The wealthy could pay for shaded seats where they had a better view, and they probably also spent much of their times betting on the races. The circus was the only place where the emperor showed himself before a populace assembled in vast numbers, and where the latter could manifest their affection or anger. The imperial box, called the pulvinar in the Circus Maximus, was directly connected to the imperial palace.

Mosaic from Lyon illustrating a chariot race with the four factions: Blue, Green, Red and White

Chariot races in the Roman era

The driver’s clothing was color-coded in accordance with his faction, which would help distant spectators to keep track of the race’s progress. According to Tertullian, there were originally just two factions, White and Red, sacred to winter and summer respectively.[48] As fully developed, there were four factions, the Red, White, Green, and Blue. Each team could have up to three chariots each in a race. Members of the same team often collaborated with each other against the other teams, for example to force them to crash into the spina (a legal and encouraged tactic). Drivers could switch teams, much like athletes can be traded to different teams today.

A rivalry between the Reds and Whites had developed by 77 BC, when during a funeral for a Red driver a supporter of the Reds threw himself on the driver’s funeral pyre. No writer of that time, however, referred to these factions as official organizations, as they were to be described in later years. Writing near the beginning of the third century, a commentator wrote that the Reds were dedicated to Mars, the Whites to the Zephyrs, the Greens to Mother Earth or spring, and the Blues to the sky and sea or autumn.[48] During his reign of 81-96 AD, the emperor Domitian created two new factions, the Purples and Golds, but these disappeared soon after he died. The Blues and the Greens gradually became the most prestigious factions, supported by emperors and the populace alike. Records indicate that on numerous occasions, Blue against Green clashes would break out during the races. The surviving literature rarely mentions the Reds and Whites, although their continued activity is documented in inscriptions and in curse tablets.

Byzantine era

Like many other aspects of the Roman world, chariot racing continued in the Byzantine Empire, although the Byzantines did not keep as many records and statistics as the Romans did. In place of the detailed inscriptions of Roman racing statistics, several short epigrams in verse were composed celebrating some of the more famous Byzantine Charioteers. The six charioteers about whom these laudatory verses were written were Anastasius, Julianus of Tyre, Faustinus, his son, Constantinus, Uranius, and Porphyrius. Although Anastasius’s single epigram reveals almost nothing about him, Porphyrius is much better known, having thirty-four known poems dedicated to him.

Constantine I (r. 306–337) preferred chariot racing to gladiatorialcombat, which he considered a vestige of paganism. However, the end of gladiatorial games in the Empire may have been more the result of the difficulty and expense that came with procuring gladiators to fight in the games, than the influence of Christianity in Byzantium. The Olympic Games were eventually ended by Emperor Theodosius I (r. 379–395) in 393, perhaps in a move to suppress paganism and promote Christianity, but chariot racing remained popular. The fact that chariot racing became linked to the imperial majesty meant that the Church did not prevent it, although gradually prominent Christian writers, such as Tertullian, began attacking the sport.[56] Despite the influence of Christianity in the Byzantine Empire, venationes, bloody wild-beast hunts, continued as a form of popular entertainment during the early days of the Empire as part of the extra entertainment that went along with chariot racing. Eventually, Emperor Leo (r. 457–474) banned public entertainments on Sundays in 469, showing that the hunts did not have imperial support, and the venationes were banned completely by Emperor Anastasius (r. 491–518) in 498. Anastasius was praised for this action by some sources, but their concern seems to be more for the danger the hunts could put humans in rather than for objections to the brutality or moral objections. There continued to be burnings and mutilations of humans who committed crimes or were enemies of the state in the hippodrome throughout the Byzantine Empire, as well as victory celebrations and imperial coronations.

The chariot races were important in the Byzantine Empire, as in the Roman Empire, as a way to reinforce social class and political power, including the might of the Byzantine emperor, and were often put on for political or religious reasons. In addition, chariot races were sometimes held in celebration of an emperor’s birthday. An explicit parallel was drawn between the victorious charioteers and the victorious emperor. The factions addressed their victors by chanting “Rejoice … your Lords have conquered” while the charioteer took a victory lap, further indicating the parallel between the charioteer’s victory and the emperor’s victory. Indeed, reliefs of Porphyrius, the famous Byzantine charioteer, show him in a victor’s pose being acclaimed by partisans, which is clearly modeled on the images on the base of Emperor Theodosius‘s obelisk. The races could also be used to symbolically make religious statements, such as when a charioteer, whose mother was named Mary, fell off his chariot and got back on and the crowd described it as “The son of Mary has fallen and risen again and is victorious.”

The Hippodrome of Constantinople (really a Roman circus, not the open space that the original Greek hippodromes were) was connected to the emperor’s palace and the Church of Hagia Sophia, allowing spectators to view the emperor as they had in Rome.[i] Citizens used their proximity to the emperor in the circuses and theatres to express public opinion, like their dissatisfaction with the Emperor’s errant policy. It has been argued that the people became so powerful that the emperors had no choice but to grant them more legal rights. However, contrary to this traditional view, it appears, based on more recent historical research, that the Byzantine emperors treated the protests and petitions of their citizens in the circuses with greater contempt and were more dismissive of them than their Roman predecessors. Justinian I (r. 527–565), for instance, seems to have been dismissive of the Greens’ petitions and to have never negotiated with them at all.

There is not much evidence that the chariot races were subject to bribes or other forms of cheating in the Roman Empire. In the Byzantine Empire, there seems to have been more cheating; Justinian I’s reformed legal code prohibits drivers from placing curses on their opponents, but otherwise there does not seem to have been any mechanical tampering or bribery. Wearing the colours of one’s team became an important aspect of Byzantine dress.

Chariot racing in the Byzantine Empire also included the Roman racing clubs, which continued to play a prominent role in these public exhibitions. By this time, the Blues (Vénetoi) and the Greens (Prásinoi) had come to overshadow the other two factions of the Whites (Leukoí) and Reds (Roúsioi), while still maintaining the paired alliances, although these were now fixed as Blue and White vs. Green and Red.[j] These circus factions were no longer the private businesses they were during the Roman Empire. Instead, the races began to be given regular, public funding, putting them under imperial control. Running the chariot races at public expense was probably a cost-cutting and labor-reducing measure, making it easier to channel the proper funds into the racing organizations. The Emperor himself belonged to one of the four factions, and supported the interests of either the Blues or the Greens.

Adopting the color of their favorite charioteers was a way fans showed their loyalty to that particular racer or faction. Many of the young men in the fan clubs, or factions, adopted extravagant clothing and hairstyles, such as billowing sleeves, “Hunnic” hair-styles, and “Persian” facial hair. There is evidence that these young men were the faction members most prone to violence and extreme factional rivalry. Some scholars have tried to argue that the factional rivalry and violence was a result of opposing religious or political views, but more likely the young men simply identified strongly with their faction for group solidarity. The factional violence was probably engaged in similarly to the violence of modern football or soccer fans. The games themselves were the usual focus of the factional violence, even when it was taken to the streets. Although fans who went to the hippodrome cheered on their favorite charioteers, their loyalty appears to be to the color for which the charioteer drove more than for the individual driver. Charioteers could change faction allegiance and race for different colors during their careers, but the fans did not change their allegiance to their color.

The Blues and the Greens were now more than simply sports teams. They gained influence in military, political,[k] and theological matters, although the hypothesis that the Greens tended towards Monophysitism and the Blues represented Orthodoxy is disputed. It is now widely believed that neither of the factions had any consistent religious bias or allegiance, in spite of the fact that they operated in an environment fraught with religious controversy. According to some scholars, the Blue-Green rivalry contributed to the conditions that underlay the rise of Islam, while factional enmities were exploited by the Sassanid Empire in its conflicts with the Byzantines during the century preceding Islam’s advent.[l]

The Blue-Green rivalry often erupted into gang warfare, and street violence had been on the rise in the reign of Justin I (r. 518–527), who took measures to restore order, when the gangs murdered a citizen in the Hagia Sophia. Riots culminated in the Nika riots of 532 AD during the reign of Justinian, which began when the two main factions united and attempted unsuccessfully to overthrow the emperor.

Chariot racing seems to have declined in the course of the seventh century, with the losses the Empire suffered at the hands of the Arabsand the decline of the population and economy. The Blues and Greens, deprived of any political power, were relegated to a purely ceremonial role. After the Nika riots, the factions grew less violent as their importance in imperial ceremony increased. In particular, the iconoclast emperor Constantine V (r. 741–775) courted the factions for their support in his campaigns against the monks. They aided the emperor in executing his prisoners and by putting on shows in which monks and nuns held hands while the crowd hissed at them. Constantine V seems to have given the factions a political role in addition to their traditionally ceremonial role. The two factions continued their activity until the imperial court was moved to Blachernae during the 12th century.

The Hippodrome in Constantinople remained in use for races, games, and public ceremonies up to the sack of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade in 1204. In the 12th century, Emperor Manuel I Komnenos (r. 1143–1180) even staged Western-style jousting matches in the Hippodrome. During the sack of 1204, the Crusaders looted the city and, among other things, removed the copper quadriga that stood above the carceres; it is now displayed at St. Mark’s Cathedral in Venice. Thereafter, the Hippodrome was neglected, although still occasionally used for spectacles. A print of the Hippodrome from the fifteenth century shows a derelict site, a few walls still standing, and the spina, the central reservation, robbed of its splendor. Today, only the obelisks and the Serpent Column stand where for centuries the spectators gathered. In the West, the games had ended much sooner; by the end of the fourth century public entertainments in Italy had come to an end in all but a few towns. The last recorded chariot race in Rome itself took place in the Circus Maximus in 549 AD.

Media related to Chariot racing at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Chariot racing at Wikimedia Commons

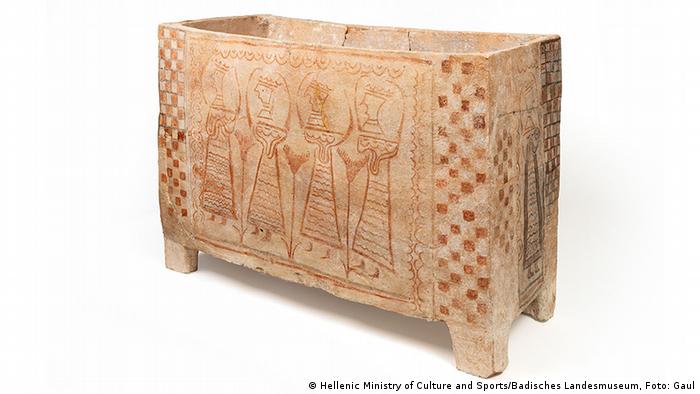

- Jump up^ A number of fragments of pottery from show two or more chariots, obviously in the middle of a race. Bennett asserts that this is a clear indication that chariot racing existed as a sport from as early as the thirteenth century BC. Chariot races are also depicted on late Geometric vases (Bennett 1997, pp. 41–48).

- Jump up^ Synoris succeeded tethrippon in 384 BC. Tethrippon was reintroduced in 268 BC (Valettas & Ioannis 1955, p. 613).

- Jump up^ Little is known of the construction of hippodromes before the Roman period (Adkins & Adkins 1998a, pp. 218–219)

- Jump up^ Τhe returning athletes also gained various benefits in their native towns, like tax exemptions, free clothing and meals, and even prize money (Bennett 1997, pp. 41–48).

- Jump up^ In Rome, chariot racing constituted one of the two types of public games, the ludi circenses. The other type, ludi scaenici, consisted chiefly of theatrical performances (Balsdon 1974, p. 248; Mus 2001–2011).

- Jump up^ There were many other circuses throughout the Roman Empire. Circus of Maxentius, another major circus, was built at the beginning of the fourth century BC outside Rome, near the Via Appia. There were major circuses at Alexandria and Antioch, and Herod the Great built four circuses in Judaea. Archaeologists working on a housing development in Essex have unearthed what they believe to be the first Roman chariot-racing arena to be found in Britain (Prudames 2005).

- Jump up^ According to the tradition, the Circus probably dated back to the time of the Etruscans (Adkins & Adkins 1998b, pp. 141–142; Boatwright, Gargola & Talbert 2004, p. 383).

- Jump up^ Roman drivers steered using their body weight; with the reins tied around their torsos, charioteers could lean from one side to the other to direct the horse’s movement, keeping the hands free for the whip and such (Futrell 2006, pp. 191–192; Köhne, Ewigleben & Jackson 2000, p. 92).

- Jump up^ The Hippodrome was situated immediately to the west of the imperial palace, and there was a private passage from the palace to the emperor’s box, the kathisma, where the emperor showed himself to his subjects. One of Justinian’s first acts on becoming emperor was to rebuild the kathisma, making it loftier and more impressive (Evans 2005, p. 16).

- Jump up^ One of the most famous charioteers, Porphyrius, was a member of both the Blues and the Greens at various times in the 5th century (Futrell 2006, p. 200).

- Jump up^ At the root of the political power eventually gained by the factions was the fact that from the mid-fifth century the making of an emperor required that he should be acclaimed by the people (Liebeschuetz 2003, p. 211).

- Jump up^ Khosrau I (r. 531–579) erected an hippodrome near Ctesiphon, and supported the Greens in deliberate contrast to his enemy, Justinian, who favored the Blues (Hathaway 2003, p. 31).

References

- Jump up^ Homer. The Iliad, 23.257–23.652.

- Jump up^ Pindar. “1.75”. Olympian Odes.

- Jump up^ Pausanias. “6.20.10–6.20.19”. Description of Greece.

- Jump up^ Pausanias. “6.20.13”. Description of Greece.

- Jump up^ Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War, 6.16.2.

- Jump up^ Pindar. Isthmian Odes, 1.1.

- Jump up^ One of them is Carrhotus who is praised by Pindar for keeping his chariot unscathed (Pindar. Pythian, 5.25-5.53). Unlike the majority of charioteers, Carrhotus was friend and brother-in-law of the man he drove for, Arcesilaus of Cyrene; so his success affirmed the success of the traditional aristocratic mode of organizing society (Dougherty & Kurke 2003, Nigel Nicholson, “Aristocratic Victory Memorials”, p. 116

- Jump up^ Potter & Mattingly 1999, Hazel Dodge, “Amusing the Masses: Buildings for Entertainment and Leisure in the Roman World”, p. 237.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Tertullian. De Spectaculis, 9.

- Jump up^ Tertullian (De Spectaculis, 16) and Cassiodorus called chariot racing an instrument of the Devil. Salvian criticized those who rushed into the circus in order to “feast their impure, adulterous gaze on shameful obscenities” (Olivová 1989, p. 86). Public spectacles were also attacked by John Chrysostom (Liebeschuetz 2003, pp. 217–218).

Primary sources

Secondary sources

- Adkins, Lesley; Adkins, Roy A. (1998a). Handbook to Life in Ancient Greece. New York, New York and Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512491-X.

- Adkins, Lesley; Adkins, Roy A. (1998b). Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome. New York, New York and Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512332-8.

- “Apobates”. Encyclopedia “The Helios” (in Greek). III. Athens, Greece. 1945–1955.

- Balsdon, John Percy Vyvian Dacre (1974). Life and Leisure in Ancient Rome. Bodley Head.

- Beard, Mary; North, John A.; Price, S. R. F. (1998). Religions of Rome: A History. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-31682-0.

- Bennett, Dirk (December 1997). “Chariot Racing in the Ancient World”. History Today. Britain. 47 (12): 41–48. Archived from the original on 2008-02-06.

- Boatwright, Mary Taliaferro; Gargola, Daniel J.; Talbert, Richard J. A. (2004). “Circuses and Chariot Racing”. The Romans: From Village to Empire. New York, New York and Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511875-8.

- Cameron, Alan (1976). Circus Factions: Blues and Greens at Rome and Byzantium. Oxford, United Kingdom: Clarendon Press.

- Cameron, Alan (1973). Porphyrius: The Charioteer. Oxford, United Kingdom: Clarendon Press.

- Camp, John Mck. (1998). Horses and Horsemanship in the Athenian Agora. Princeton, New Jersey: The American School of Classical Studies at Athens. ISBN 0-87661-639-2.

- Evans, James Allan Stewart (2005). “The Nika Revolt of 532”. The Emperor Justinian and the Byzantine Empire. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-32582-0.

- Dougherty, Carol; Kurke, Leslie (2003). The Cultures Within Ancient Greek Culture: Contact, Conflict, Collaboration. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81566-5.

- Finley, Moses I.; Pleket, H. W. (1976). The Olympic Games: The First Thousand Years. New York, New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-52406-9.

- Freeman, Charles (April 2004). “St Mark’s Square: An Imperial Hippodrome?”. History Today. Britain: History Today. 54 (4): 39.

- Futrell, Alison (2006). The Roman Games: A Sourcebook. Malden, Massachusetts and Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing Limited. ISBN 1-4051-1569-6.

- Gagarin, Michael (January 1983). “Antilochus’ Strategy: The Chariot Race in Iliad 23”. Classical Philology. Britain: The University of Chicago Press. 78 (1): 35–39. doi:10.1086/366744. JSTOR 269909.

- Golden, Mark (2004). Sport in the Ancient World from A to Z. New York, New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24881-7.

- Gregory, Timothy E. (2010). A History of Byzantium. Malden, Massachusetts: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 1-4051-8471-X.

- Harris, Harold Arthur (1972). Sport in Greece and Rome. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-0718-4.

- Hathaway, Jane (2003). “Bilateral Factionalism in Ottoman Egypt”. A Tale of Two Factions: Myth, Memory, and Identity in Ottoman Egypt and Yemen. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-5883-0.

- Humphrey, John H. (1986). Roman Circuses: Arenas for Chariot Racing. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California. ISBN 978-0-520-04921-5.

- Köhne, Eckart; Ewigleben, Cornelia; Jackson, Ralph (2000). Gladiators and Caesars: The Power of Spectacle in Ancient Rome. British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-2316-5.

- Kyle, Donald G. (1993) [1987]. Athletics in Ancient Athens. Leiden, The Netherlands: E.J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-09759-7.

- Kyle, Donald G. (2007). Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World. Malden, Massachusetts and Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing Limited. ISBN 0-631-22971-X.

- Lançon, Bertrand (2000). “Festivals and Entertainments”. Rome in Late Antiquity: Everyday Life and Urban Change, AD 312-609. New York, New York and London, United Kingdom: Routledge (Taylor & Francis). ISBN 0-415-92976-8.

- Laurence, Ray (1996) [1994]. Roman Pompeii: Space and Society. New York, New York and London, United Kingdom: Routledge (Taylor & Francis). ISBN 0-415-14103-6.

- Liebeschuetz, John Hugo Wolfgang Gideon (2003). “Shows and Factions”. The Decline and Fall of the Roman City. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926109-1.

- McComb, David G. (2004). Sports in World History. New York, New York and London, United Kingdom: Routledge (Taylor & Francis). ISBN 0-415-31811-4.

- Meijer, Fik; Waters, Liz (2010). Chariot Racing in the Roman Empire. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-9697-5.

- Mus, P. Dionysius (2001–2011). “Ludi Circenses (longer version)”. Societas via Romana. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- Neils, Jenifer; Tracy, Stephen V. (2003). Games at Athens. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens. ISBN 0-87661-641-4.

- Olivová, Věra (1989). “Chariot Racing in the Ancient World”. Nikephoros – Zeitschrift für Sport und Kultur im Altertum. Weidmann. 2: 65–88. ISBN 3-615-00058-7.

- Polidoro, J. Richard; Simri, Uriel (May–June 1996). “The Games of 676 BC: A Visit to the Centenary of the Ancient Olympic Games”. The Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance. American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance. 67 (5): 41–46.

- Potter, David Stone; Mattingly, D. J. (1999). Life, Death, and Entertainment in the Roman Empire. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08568-9.

- Potter, David Stone (2006). A Companion to the Roman Empire. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-631-22644-3.

- Prudames, David (5 January 2005). “Roman Chariot-Racing Arena Is First to Be Unearthed in Britain”. Culture 24. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- Ramsay, William Wardlaw (1876). “Games of the Circus”. A Manual of Roman Antiquities. London: Charles Griffin and Company.

- Scullard, Howard Hayes (1981). Festivals and Ceremonies of the Roman Republic. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-1402-4.

- Struck, Peter (2 August 2010). “Greatest of All Time”. Lapham’s Quarterly. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- Treadgold, Warren T. (1997). “The Refoundation of the Empire, 284-337”. A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2630-2.

- Valettas, G. M.; Ioannis, Passas (1945–1955). “Chariot Racing”. Encyclopedia “The Helios” (in Greek). III. Athens, Greece.

- Vikatou, Olympia (2007). “Hippodrome of Olympia – Description”. Hellenic World Heritage Monuments. Hellenic Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- Waldrop, Murray (13 August 2010). “Wealth of today’s sports stars is ‘no match for the fortunes of Rome’s chariot racers‘“. The Telegraph. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chariot_racing

http://www.giacobbegiusti.com