Giacobbe Giusti, ETRUSCAN MAN, Chiusi Museum

Giacobbe Giusti, ETRUSCAN MAN, Chiusi Museum

Giacobbe Giusti, ETRUSCAN MAN, Chiusi Museum

Giacobbe Giusti, ETRUSCAN MAN, Chiusi Museum

imGiacobbe Giusti, SANDRO BOTTICELLI: SIMONETTA VESPUCCI

Giacobbe Giusti, SANDRO BOTTICELLI: SIMONETTA VESPUCCI

Giacobbe Giusti, SANDRO BOTTICELLI: SIMONETTA VESPUCCI

Giacobbe Giusti, SANDRO BOTTICELLI: SIMONETTA VESPUCCI

Giacobbe Giusti, SANDRO BOTTICELLI: SIMONETTA VESPUCCI

Giacobbe Giusti, Piero di Cosimo: SIMONETTA VESPUCCI

Giacobbe Giusti, Piero di Cosimo: SIMONETTA VESPUCCI

Portrait of a woman, said to be of Simonetta Vespucci (c. 1490) by Piero di Cosimo

|

|

| Born | 1453[1] Genoa or Portovenere, Liguria, Italy |

| Died | 26 April 1476(1476-04-26) (aged 22–23)[1] Florence, Italy |

| Spouse(s) | Marco Vespucci |

| Parent(s) | Gaspare Cattaneo Della Volta and Cattocchia Spinola |

Simonetta Vespucci (née Cattaneo; 1453 – 26 April 1476[1]), nicknamed la bella Simonetta, was an Italian noblewoman from Genoa, the wife of Marco Vespucci of Florence and the cousin-in-law of Amerigo Vespucci. According to her legend, before her death at 22 she was famous as the greatest beauty of her age in North Italy, and the model for many paintings (many not showing similar features at all) by Botticelli and other Florentine painters. Many art historians are infuriated by these attributions, which the Victorian critic John Ruskin is blamed for giving some respectability.[2]

She was born as Simonetta Cattaneo circa 1453 in a part of the Republic of Genoa that is now in the Italian region of Liguria. A more precise location for her birthplace is unknown: possibly the city of Genoa,[3] or perhaps either Portovenere or Fezzano.[4] The Florentine poet Politian wrote that her home was “in that stern Ligurian district up above the seacoast, where angry Neptune beats against the rocks … There, like Venus, she was born among the waves.”[5] Her father was a Genoese nobleman named Gaspare Cattaneo della Volta (a much-older relative of a sixteenth-century Doge of Genoa named Leonardo Cattaneo della Volta) and her mother was Gaspare’s wife, Cattocchia Spinola (another source names her parents slightly differently as Gaspare Cattaneo and Chateroccia di Marco Spinola.[6]

At age fifteen or sixteen she married Marco Vespucci, son of Piero, who was a distant cousin of the explorer and cartographer Amerigo Vespucci. They met in April 1469; she was with her parents at the church of San Torpete when she met Marco; the doge Piero il Fregoso and much of the Genoese nobility were present.

Marco had been sent to Genoa by his father, Piero, to study at the Banco di San Giorgio. Marco was accepted by Simonetta’s father, and he was very much in love with her, so the marriage was logical. Her parents also knew the marriage would be advantageous because Marco’s family was well connected in Florence, especially to the Medici family.

Simonetta and Marco were married in Florence. According to her legend, Simonetta was instantly popular at the Florentine court. The Medici brothers, Lorenzo and Giuliano took an instant liking toward her. Lorenzo permitted the Vespucci wedding to be held at the palazzo in Via Larga, and held the wedding reception at their lavish Villa di Careggi. Simonetta, upon arriving in Florence, was discovered by Sandro Botticelli and other prominent painters through the Vespucci family. Before long she had supposedly attracted the brothers Lorenzo and Giuliano of the ruling Medici family. Lorenzo was occupied with affairs of state, but his younger brother was free to pursue her.

At La Giostra (a jousting tournament) in 1475, held at the Piazza Santa Croce, Giuliano entered the lists bearing a banner on which was a picture of Simonetta as a helmeted Pallas Athene painted by Botticelli, beneath which was the French inscription La Sans Pareille, meaning “The unparalleled one”.[7] It is clear that Simonetta had a reputation as an exceptional beauty in Florence,[8] but the whole display should be considered within the conventions of courtly love; Simonetta was a married woman,[9] a member of a powerful family allied to the Medici,[10] and any actual affair would have been a huge political risk.

Giuliano won the tournament,[11] and Simonetta was nominated “The Queen of Beauty” at that event. It is unknown, and unlikely, that they actually became lovers.

Simonetta Vespucci died just one year later, presumably from tuberculosis,[12] on the night of 26–27 April 1476. She was twenty-two at the time of her death. She was carried through the city in an open coffin for all to admire her beauty, and there seems to have been some kind of posthumous popular cult in Florence.[13] Her husband remarried soon afterward, and Giuliano de Medici was assassinated in the Pazzi conspiracy in 1478, two years to the day after her death.

Botticelli finished painting The Birth of Venus around 1486, some ten years later. Some have claimed that Venus, in this painting, closely resembles Simonetta.[14] This claim, however, is dismissed as a “romantic myth” by Ernst Gombrich,[15] and “romantic nonsense” by historian Felipe Fernández-Armesto:

The vulgar assumption, for instance, that she was Botticelli’s model for all his famous beauties seems to be based on no better grounds than the feeling that the most beautiful woman of the day ought to have modelled for the most sensitive painter.[16]

Some, including Ruskin, suggest that Botticelli also had fallen in love with her, a view supported by his request to be buried in the Church of Ognissanti – the parish church of the Vespucci – in Florence. His wish was carried out when he died some 34 years later, in 1510. However this had been Botticelli’s parish church since he was baptized there, and he was buried with his family. The church contained works by him.

There are some connections between Simonetta and Botticelli. He painted the standard carried by Giuliano at the joust in 1475, which carried an image of Pallas Athene that was very probably modelled on her; so he does seem to have painted her once at least, though the image is now lost.[17] Botticelli’s main Medici patron, Giuliano’s younger cousin Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici, married Simonetta’s niece Semiramide in 1482, and it is often thought that his Primavera was painted as a wedding gift on this occasion.[18]

Portrait of a Woman by the workshop of Sandro Botticelli, mid-1480s[19]

Flora in Botticelli’s Birth of Venus

Detail of one of the Three Graces in Primavera by Botticelli

Detail of the Venus figure in Primavera by Sandro Botticelli, circa 1482

Detail of the Venus figure in The Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli, circa 1484-1486

A Satyr mourning over a Nymph by Piero di Cosimo, circa 1495

Regarding each Portrait of a Woman pictured above that is credited to the workshop of Sandro Botticelli, Ronald Lightbown claims they were creations of Botticelli’s workshop that were likely neither drawn nor painted exclusively by Botticelli himself. Regarding these same two paintings he also claims “[Botticell’s work]shop…executed portraits of ninfe, or fair ladies…all probably fancy portraits of ideal beauties, rather than real ladies.”[20]

She may be depicted in the painting by Piero di Cosimo titled Portrait of a woman, said to be of Simonetta Vespucci that portrays a woman as Cleopatra with an asp around her neck and is alternatively titled by some individuals Portrait of Simonetta Vespucci. Yet how closely this resembles the living woman is uncertain, partly because if this is indeed a rendering of her form and spirit it is a posthumous portrait created about fourteen years after her death. Worth noting as well is the fact that Piero di Cosimo was only fourteen years old in the year of Vespucci’s death. The museum that currently houses this painting questions the very identity of its subject by titling it “Portrait of a woman, said to be of Simonetta Vespucci”, and stating that the inscription of her name at the bottom of the painting may have been added at a later date.[21]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simonetta_Vespucci

Dieu invite Noé à quitter l’Arche L’intérieur de la chapelle est de style byzantin, il date de la fin de la décennie 1130, jusque dans les années 1150-1160 Au Xe siècle, la Sicile est rattachée au califat fatimide du Caire. L’île reste sous domination musulmane jusqu’à l’arrivée des Normands, qui, en 1059, obtiennent la souveraineté des mains de la Papauté décidée à rechristianiser des territoires que Byzance n’était plus capable de reconquérir. La conquête normande s’échelonne entre 1060 à 1090. Finalement, en 1130, Roger II (1130-1154) obtient la couronne de l’antipape Anaclet II (1130-1138) et rassemble les territoires normands en un royaume, choisissant naturellement Palerme comme capitale. Il y fait construire un palais et, dans celui-ci, un riche édifice cultuel, la Chapelle palatine, qui, par son architecture et son décor, demeure un exemple exceptionnel de métissage des arts chrétiens d’Orient et d’Occident, et d’art islamique.

_(7026706823).jpg)

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosaici_della_Cappella_Palatina

Giacobbe Giusti, Santa Maria Nuova cathedral, Monreale, Sicily

Giacobbe Giusti, Santa Maria Nuova cathedral, Monreale, Sicily

Cathedral of Monreale, Sicily, Italy. Mosaics of the north side of the nave.

Giacobbe Giusti, Santa Maria Nuova cathedral, Monreale, Sicily

Cathedral of Monreale, Sicily, Italy. Mosaics of the south side of the nave.

Giacobbe Giusti, Santa Maria Nuova cathedral, Monreale, Sicily

Italy, Sicily, Monreale, Cathedral

Giacobbe Giusti, Santa Maria Nuova cathedral, Monreale, Sicily

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monreale#The_Cathedral

Giacobbe Giusti, PIETRO CAVALLINI: mosaics at the apse of Basilica di Santa Maria in Trastevere

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pietro_Cavallini

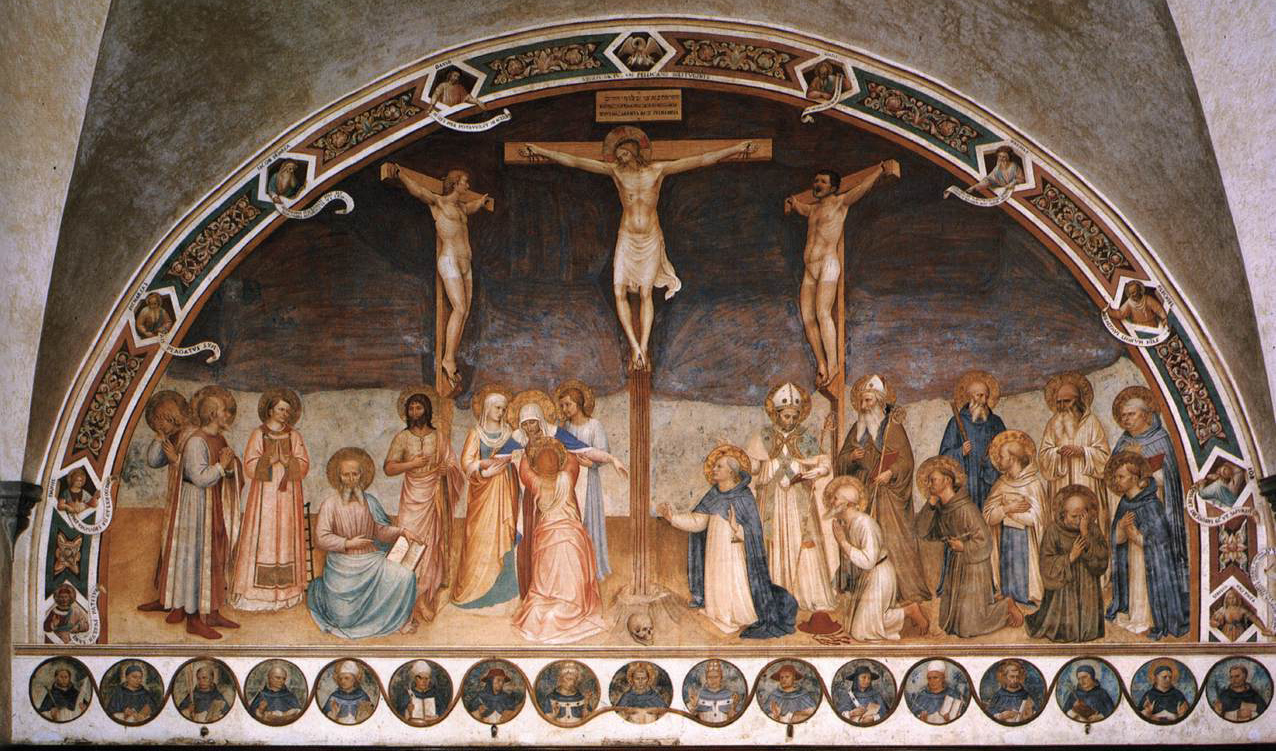

Giacobbe Giusti, Giotto Cruxifixion

Kiss of Judas, one of the panels in the Scrovegni Chapel.

The Scrovegni Chapel (Italian: ”Cappella degli Scrovegni”, also known as the Arena Chapel), is a church in Padua, Veneto, Italy. It contains a fresco cycle by Giotto, completed about 1305 and considered to be an important masterpiece of Western art. The nave is 20.88 metres long, 8.41 metres wide, and 12.65 metres high. The apse area is composed of a square area (4.49 meters deep and 4.31 meters wide) and a pentagonal area (2.57 meters deep).

The church was dedicated to Santa Maria della Carità at the Feast of the Annunciation, 1303, and consecrated in 1305. Giotto’s fresco cycle focuses on the life of the Virgin Mary and celebrates her role in human salvation. A motet by Marchetto da Padova appears to have been composed for the dedication on 25 March 1305.[1] The chapel is also known as the Arena Chapel because it was built on land purchased by Enrico Scrovegni that abutted the site of a Roman arena. The space was where an open-air procession and sacred representation of the Annunciation to the Virgin had been played out for a generation before the chapel was built.

The Arena Chapel was commissioned from Giotto by the affluent Paduan banker, Enrico Scrovegni. In the early 1300s Enrico purchased from Manfredo Dalesmanini the area on which the Roman arena had stood. Here he had his luxurious palace built, as well as a chapel annexed to it. The chapel’s project was twofold: to serve as the family’s private oratory and as a funerary monument for himself and his wife. Enrico commissioned Giotto, the famous Florentine painter, to decorate his chapel. Giotto had previously worked for the Franciscan friars in Assisi and Rimini, and had been in Padua for some time, working for the Basilica of Saint Anthony in the Sala del Capitolo and in the Blessings’s Chapel. A number of 14th-century sources (Riccobaldo Ferrarese, Francesco da Barberino, 1312-1313) testify to Giotto’s presence at the Arena Chapel’s site. The fresco cycle can be dated with a good approximation to a series of documentary testimonies: the purchase of the land took place on 6 February 1300; the bishop of Padua, Ottobono dei Razzi, authorised the building some time prior to 1302 (the date of his transferal to the Patriarcato of Aquileia); the chapel was first consecrated on 25 March 1303, the day of the Annunciation; on 1 March 1304 Pope Benedict XI granted an indulgence to whomever would have visited the Chapel; one year later on 25 March 1305 the chapel received its definitive consecration. Giotto’s work thus falls in the period from 25 March 1303 to 25 March 1305.

Giotto painted the chapel’s inner surface following a comprehensive iconographic and decorative project which Giuliano Pisani identified in his book I volti segreti di Giotto. Le rivelazioni della Cappella degli Scrovegni (Rizzoli, 2008) as being the work of the Augustinian theologian, Friar Alberto da Padova. Among the sources utilized by Giotto following Friar Alberto’s advice are the Apocryphal Gospels of Pseudo-Matthew and Nicodemus, the Golden Legend (Legenda aurea) by Jacopo da Varazze (Jacobus a Varagine) and, for a few minute iconographic details, Pseudo-Bonaventura’s Meditations on the Life of Jesus Christ, as well as a number of Augustinian texts, such as De doctrina Christiana, De libero arbitrio, De Genesi contra Manicheos, De quantitate animae, and other texts from the Medieval Christian tradition, among which is the Phisiologus.[2]

Giotto, who was born around 1267, was 36–38 years old when he worked at Enrico Scrovegni’s chapel. He had a team of about 40 collaborators, and they calculated that 625 work days were necessary to paint the chapel. A “work day” meant that portion of each fresco that could be painted before the plaster dried and was no longer “fresh” (fresco in Italian ).

In January 1305, friars from the nearby Church of the Eremitani filed a complaint to their bishop, protesting that Scrovegni had not respected the original agreement. Scrovegni was transforming his private oratory into a church with a bell tower, thus producing unfair competition with the Eremitani’s activities. We do not know what happened next, but it is likely that, as a consequence of this complaint, the monumental apse and the wide transept were demolished. Both are visible on a model of the church painted by Giotto on the counter-facade (the Last Judgement). The apse was the section where Enrico Scrovegni had meant to have his tomb. The presence of frescoes dating to after 1320 supports the demolition hypothesis proposed by Giuliano Pisani. The apse, the most significant area in all churches, is where Enrico and his wife, Lacopina d’Este, were buried. This apse presents a narrowing of the space which gives a sense of its being incomplete and inharmonious. When one observes the lower frame of the triumphal arch, right above Saint Catherine of Alexandria’s small altar piece, one notices that Giotto’s perfect symmetry is altered by a fresco decoration representing two medallions with busts of female saints, a lunette with Christ in glory, and two episodes from the Passion (the prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane and the flogging of Jesus), which together give an overall sense of disharmony. The artist who painted these scenes also painted the greater part of the apse, an unknown artist called “The Master of the Scrovegni Choir” who worked at the Chapel about twenty years after Giotto’s work was completed. The main focus of the unknown artist’s work is constituted by six monumental scenes on the side walls of the chancel that depict the last period of Mary’s earthly life. This choice is in tune with the iconographic program inspired by Alberto da Padova and painted by Giotto.

The chapel was originally connected with the Scrovegni palace, which was built on what remained of the foundations of the elliptical ancient Roman arena. The palace was demolished in 1827 in order to sell the precious materials it contained and to erect two condominiums in its place. The chapel was purchased by the Municipality of the City of Padua in 1881, a year after the City Council’s deliberation of 10 May 1880 leading to a decision to demolish the condominiums and restore the chapel. In June 2001, following a preparation study lasting over 20 years, the Istituto Centrale per il Restauro (Central Institute for Restoration) of the Ministry for Cultural Activities, in collaboration with Padua’s Town Hall in its capacity of owner of the Arena Chapel, started a full-scale restoration of Giotto’s frescoes under the late Giuseppe Basile’s technical direction. In 2000 the consolidation and restoration of the external surfaces had been completed and the adjacent “Corpo Tecnologico Attrezzato” (CTA) had been installed. In this “equipped technological chamber” visitors wait for fifteen minutes to allow their body humidity to be lowered and any accompanying smog dust to be filtered out. In March 2002 the chapel was reopened to the public in its original splendor. A few problems remain unsolved, such as flooding in the crypt under the nave due to the presence of an underlying aquifer, and the negative effect on the building’s stability of the cement inserts that replaced the original wooden ones in the 1960s.

Giuliano Pisani’s studies proved a number of commonly held beliefs concerning the chapel to be groundless, among them, the notion that Dante inspired Giotto. Another claim was that the theological program followed by Giotto is based on Saint Thomas, but it has proven to be wholly Augustinian. The conjecture that the Frati Gaudenti fraternity, of which Enrico Scrovegni was a member, influenced the content of Giotto’s fresco cycle has been proved wrong. Also disproved is the belief that Enrico Scrovegni required that the iconography program have no emphasis placed on the sin of usury. Giuliano Pisani pointed out that Dante’s condemnation of Scrovegni’s father, Reginaldo, as a usurer in Canto 17 of the Inferno dates to a few years after Giotto’s completion of the chapel, so it cannot be regarded as a motive behind any theological anxieties on the part of Enrico Scrovegni.

At a deeper level of analysis, a tenet of Giotto scholarship was for a long time the belief that Giotto had made a number of theological mistakes. For instance, Giotto placed Hope after Charity in the Virtues series, and did not include Avarice in the Vices series, due to the usual representation of Enrico Scrovegni as a usurer. Giuliano Pisani has proved that Giotto followed a precise and faultless theology based on Saint Augustine in a program which was devised by Friar Alberto da Padova. Giuliano Pisani’s discovery of the Augustinian inspiration for the frescoes with Friar Alberto da Padova as the intermediary shows that what used to be considered mistakes, whether intentional or not on Giotto and Enrico’s part, now appear to be elements of a perfectly balanced theological program. Avarice, far from being “absent” in Giotto’s cycle, is portrayed with Envy, forming with it a fundamental component of a more comprehensive sin. For this reason Envy is placed facing the virtue of Charity, to indicate that Charity is the exact opposite of Envy, and that in order to cure oneself of the sin of Envy one needs to learn from Charity. Charity crushes Envy’s money bag under her feet, while on the opposite wall red flames burn under Envy’s feet. [3]

Giotto frescoed the chapel’s whole surface, including the walls and the ceiling. The fresco cycle is organised along four tiers, each of which contains episodes from the stories of the various protagonists of the Sacred History. Each tier is divided into frames, each forming a scene. The chapel is asymmetrical in shape, with six windows on the longer south wall, and this shape determined the layout of the decoration. The first step was choosing to place two frames between each double window set on the south wall; secondly, the width and height of the tiers was fixed in order to calculate the same space on the opposite north wall.

The cycle recounts the story of salvation. It starts from high up on the lunette of the triumphal arch, when God the Father decides on reconciliation with humanity, entrusting the archangel Gabriel with the announcement of his decision to erase Adam’s sin with the sacrifice of His son. The narrative continues with the stories of Joachim and Anne (first tier from the top, south wall) and the stories of Mary (first tier from the top, north wall). After a return to the triumphal arch, the scenes of the Annunciation and the Visitation follow. The stories of Christ were placed on the middle tier of the south and north walls. The scene of Judas receiving the money to betray Jesus is on the triumphal arch. The lower tier of the south and north walls shows the Passion and Resurrection; the last frame on the north wall shows the Pentecost. The fourth tier begins at ground level with the monochromes of the Vices (north wall) and the Virtues (south wall). The west wall (counter-façade) presents the Last Judgment.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scrovegni_Chapel

Giacobbe Giusti, Piero Cavallini: Crocifissione

http://www.settemuse.it/pittori_scultori_italiani/pietro_cavallini.htm

Giacobbe Giusti: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World

by Mike Boehm Los Angeles Times

Here’s a paradox: Today’s art lovers would recoil at the thought of travel disasters, building collapses or volcanic eruptions afflicting their own communities. But over the next three months, visitors to the Getty Museum can enjoy a unique display of bronze statuary that was saved for posterity precisely because such calamities befell its ancient owners.

The show is “Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World,” running Tuesday to Nov. 1 at the Getty Center in Brentwood — an atypical venue for an ancient-art show, which normally would be seen at the Getty Villa in Pacific Palisades.

ADVERTISEMENT

The two Getty curators who spent seven years organizing “Power and Pathos” say the 46 rare bronzes in the show needed to be seen in the best light and from all angles. The special exhibitions galleries in Brentwood afford space and natural lighting that the Villa lacks.

Essential Arts & Culture: A curated look at SoCal’s wonderfully vast and complex arts world

Having spent up to 2,300 years buried far below the ground or sunken in ocean beds of the Mediterranean Sea, this is art that deserves a deluxe presentation, given all it has been through.

What’s most special about the exhibition, curators Jens Daehner and Kenneth Lapatin say, is that it’s the first to bring together so many prized and exceedingly rare works of its period and kind.

lFull Coverage

Gallery and museum reviews: Full coverage

Gallery and museum reviews: Full coverage

For scholars it’s an unprecedented opportunity to eyeball one-fourth of the world’s known Hellenistic bronzes in one place, comparing and contrasting and perhaps leading to new understanding of how these works were created and what they meant to their ancient public.

For museum-goers, “Power and Pathos” is a chance to get a good sense of the complex currents that influenced creativity between the golden age of Greece, which historians call the “classical” period, and the dawn of the Roman Empire. The seeds of today’s conceptions about what art is for were planted in the Hellenistic world, as a burgeoning nonroyal upper class formed history’s first art market and began to commission works reflecting themselves rather than their rulers and their gods.

“All of what we have survived by chance, and we’re lucky to have it. How many more statues are under the sea bed or underground waiting to be pulled up, we don’t know.

— Kenneth Lapatin, curator

The Hellenistic period spans nearly 300 years, from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC to Augustus Caesar’s triumph over Cleopatra and Mark Antony in 31 BC. The Egyptian queen was the last descendant of Ptolemy, one of the generals who had divided Alexander’s empire, which sprawled from Greece to what’s now Pakistan.

With a few exceptions, the statues on display were lost for centuries. Some were excavated starting in the 1700s from sites such as Herculaneum in Italy, which perished along with Pompeii in the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in A.D. 79. Many were pulled from coastal waters off Italy, Greece, Croatia, Tunisia and Turkey, where ancient cargo ships had been scuttled by pirates or wrecked by storms. One star attraction, a bronze sculpture of a seated boxer with bandaged hands and a battered, broken-nosed face and cauliflower ears, was placed in a deep pit at the bottom of an ancient wall in Rome for reasons that remain a mystery.

“All of what we have survived by chance, and we’re lucky to have it,” said Lapatin, whose vertical shock of hair makes him the Lyle Lovett of antiquarians. “How many more statues are under the sea bed or underground waiting to be pulled up, we don’t know. They were ubiquitous in antiquity, but they are rare today.”

Bronze was valuable and easily repurposed for myriad practical uses, so statues made of the metal became antiquity’s equivalent of the passenger pigeon — except for about 200 known exceptions. “You also had ideological reasons” for their wholesale destruction, Lapatin said. “Early Christians weren’t interested in preserving nude statues of pagan gods, and this was ready cash.”

That disaster kept a precious few bronzes from destruction “is the utter paradox” that underlies the show, said Daehner, an affable, soft-spoken German. “You could call it the paradox of archaeology in general, but for bronze it’s particularly true and poignant.”

Silver lining

The show is itself a silver lining of sorts. It had its genesis in the 2007 settlement of the Italian government’s grievances over looted ancient artworks the Getty had acquired, in which the museum returned 40 suspect pieces to Italy, including some of its most prized holdings. But with the return of comity and cooperation, Getty curators could now approach the great museums of Italy with ideas for art loans and collaboration on exhibitions. In 2008 the Getty entered a pact for art exchanges with the National Archaeological Museum in Florence.

Looking for intersections between the collections, curators noted that each sported magnificent Hellenistic bronzes — among them the “Getty Bronze,” a famous statue of a young athlete that was netted from the Aegean Sea by Italian fisherman, and the “Herm of Dionysos,” a Getty-owned example of one of the quirkiest forms of ancient art.

From there, they approached dozens of other museums, landing loans from 30 institutions in 12 countries — among them the Metropolitan Museum, the Smithsonian Institution, British Museum, the Prado and the Louvre.

“Many are national treasures or highlights of a museum,” Lapatin said. That so many pitched in — often with works never seen before in the United States — shows how strong the exhibition’s allure has been for scholars of ancient art. “It’s a testament to bringing them out of splendid isolation to [the Getty], where they’re talking to each other. No one has ever done this before.”

Today’s international politics kept a few desired sculptures out of reach. “There are pieces in Baghdad and Tehran that would have been very interesting to have in the show,” Daehner said. “In 2008 the world looked very different than it is now,” and getting them momentarily had seemed possible.

The display of the Getty’s two prime Hellenistic bronzes embodies the quest for consonance, comparison and contrast that Daehner and Lapatin were after. Viewers will get a simultaneous glimpse of the life-size “Getty Bronze,” which usually occupies a room of its own at the Villa, alongside similar works from the British Museum and the Museum of Underwater Antiquities in Athens. Together, Daehner said, they reflect the Hellenistic convention of idealizing the human body, yet making it more accessibly natural than would have been the case in the 400s BC and earlier.

Herms were boundary markers with a sculpted head at the top of a narrow pedestal and male genitalia poking out farther down. The genre gets its name from the god Hermes, whose head frequently topped the markers. The Getty’s herm shows a head of the god Dionysos, its hat and beard calling to mind portraits of the English King Henry VIII. To its right stands a near doppelganger fetched from coastal waters of Tunisia.

Were they made by the same sculptor or workshop? If so, why is the coloration so different, and why does the Tunisian herm have subtle, intricate touches — such as a fully detailed head of hair on the back of his scalp — that the Getty version is missing?

ADVERTISEMENT

The word “pathos” in the show’s title reflects the objects’ lost-and-found history of past tragedy as well as Hellenistic sculptors’ key aesthetic breakthrough — using bronze, which is more pliable than marble, to register in acute detail the often careworn lives of mere mortals after centuries in which the main purpose of statuary was to capture the otherworldly majesty of gods and heroes.

A gallery devoted to depictions of ordinary humans rather than gods or rulers shows how Hellenistic sculptors began to embody common feelings. The face of a large “Portrait Statue of a Boy,” dug from the sands on the island of Crete, wears a look that projects sneering disgust mixed with an aching throb of sadness. The angsty defiance of adolescents apparently predates Holden Caulfield and Kurt Cobain by two millennia.

“Our modern idea of capturing character or personality is something that happens in the Hellenistic age that isn’t there before,” Daehner said. “Expression, emotion and a certain psychological realism get into a portrait.”

The Hellenistic period was the era when Greece had ceased being a great power in the Mediterranean world, yet it triumphed culturally by spreading its styles and ideas far beyond the reaches of the Athenian empire at its height in the 400s BC.

Alexander, the Macedonian king whose father had conquered Greece, carried his sword — and Greek notions about art and philosophy that he’d learned from his teacher, Aristotle — through most of the world known to ancient Europeans.

Lapatin said that one way to understand what was happening in bronze sculpture during the era is to follow the money.

“It’s an economic development,” he said. “In the classical period if you were wealthy you made a donation to the sanctuary” and commissioned a statue of a god. “In Hellenistic times, you could decorate your villa. The wealthy had more options, and a lot was about displaying statues and showing you were wealthy and cultured.” The vast sacked riches of Persia, Alexander’s key conquest, contributed mightily to enlarging this new class of private art consumers, Lapatin said.

The show that brings together so much begins with nothing at all: an empty, broken stone pedestal that, like many others across the landscape from the eastern Mediterranean to central Asia, sports an inscription but no statue.

“It’s signed by Lysippos, the favorite sculptor of Alexander the Great,” Lapatin said. Lysippos was credited in ancient times with having created more than 1,500 bronze statues, “none of which survives,” he said, except via copies made by others.

While Hellenistic artists and their public responded to new cultural currents, they did not turn their backs on tradition. A bust of a man, signed by the Greek sculptor Apollonios, is a blatant knockoff of a famous full-length statue of a spear-carrier by Polykleitos, who’d lived 400 years earlier.

“The original is famous, but it’s a good copy, so he signs it,” Lapatin said. “It’s got the cachet of an old master.” As a business move, that seems downright contemporary.

Although it is organized by the two Getty curators, “Power and Pathos” first was seen at the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence. Its last stop, after the Getty, is the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

mes.com/entertainment/arts/la-ca-cm-getty-hellenistic-bronze-20150726-story.html

http://www.giacobbegiusti.com

Giacobbe Giusti, Roman statues of runners found at Herculaneum

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Villa_dei_Papiri

http://www.GiacobbeGiusti.com