Giacobbe Giusti, Basilica of the Holy House

Giacobbe Giusti, Basilica of the Holy House

Creating User:Parsifall

Giacobbe Giusti, Basilica of the Holy House

Creating User:Claudio.stanco

Giacobbe Giusti, Basilica of the Holy House

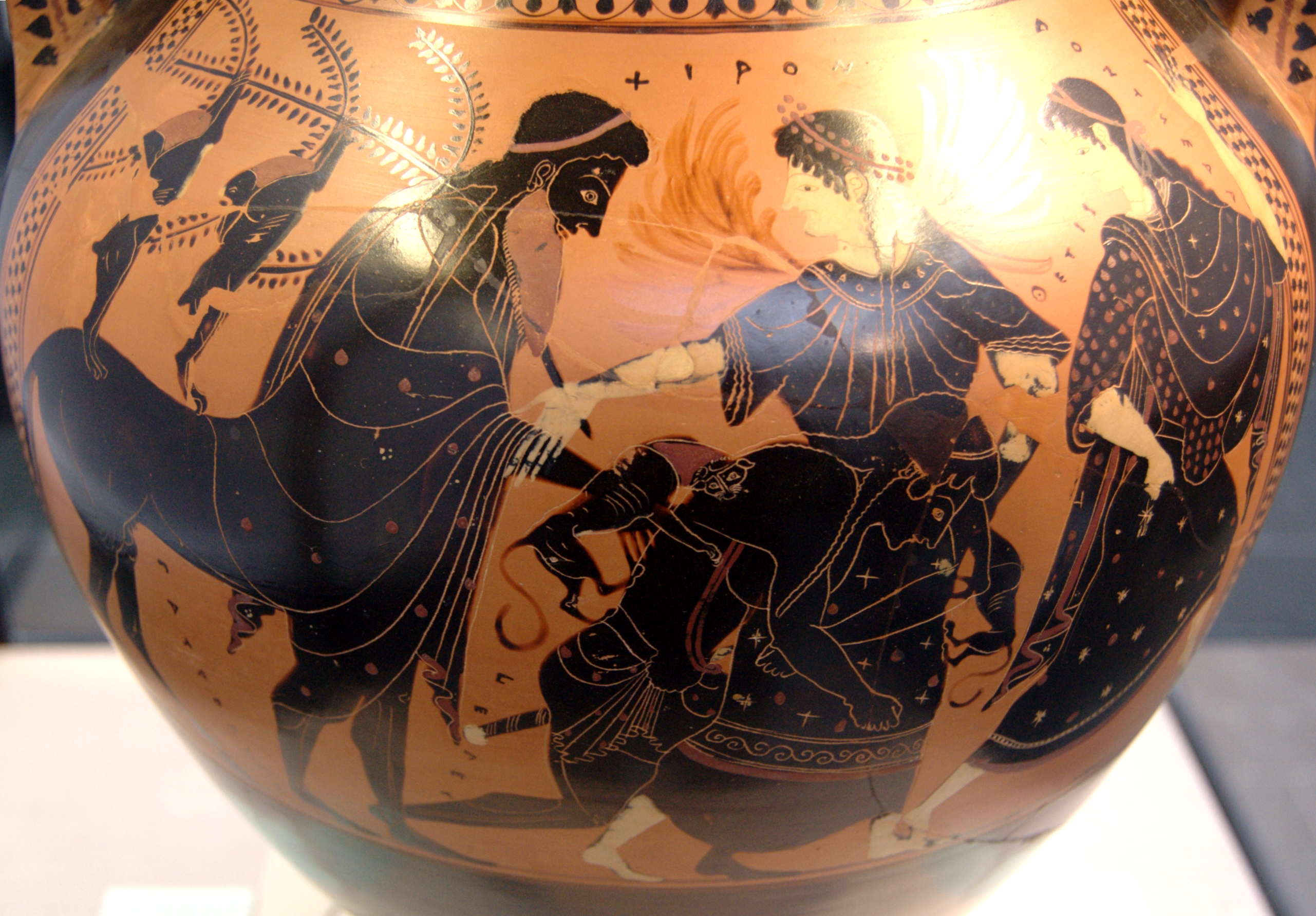

Antonio di girolamo lombardo coi figli pietro, paolo e giacomo, porta centrale del santuario di loreto

User:Sailko

| Basilica della Santa Casa

Giacobbe Giusti, Basilica of the Holy House

|

|

|---|---|

The façade edifice of the Basilica della Santa Casa.

|

|

| Location | Loreto, Marche, Italy |

| Denomination | Catholic Church |

| History | |

| Status | Pontifical minor basilica |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Late Gothic |

| Completed | 16th century |

| Administration | |

| Episcopal area | Territorial Prelature of Loreto |

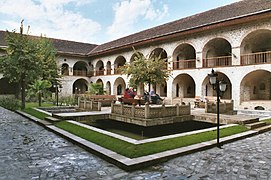

The Basilica della Santa Casa(English: Basilica of the Holy House) is a shrine of Marian pilgrimage in Loreto, Italy. The basilica is known for enshrining the house in which the Blessed Virgin Mary is believed by some Catholics to have lived. Pious devotees believe that the same house was flown over by Angelic beings from Jerusalem to Tersatto (Trsat in Croatia) then to Recanati before arriving at the current site. [1][2]

Pope Benedict XV designated the Blessed Virgin Mary under the same title to be Patroness of air passengers and auspicious travel on 24 March 1920. Accordingly, Pope Pius XIgranted a Canonical Coronation to the image of Our Lady of Loreto made of Cedar of Lebanon on 5 September 1922, replacing the torched image consumed in fire on 23 February 1921.

Historic structure

The basilica is a Late Gothic structure continued by Giuliano da Maiano, Giuliano da Sangallo and Donato Bramante.[3] It is 93 meters long, 60 meters wide, and its campanile is 75.6 meters high.

The façade of the church was erected under Sixtus V, who in 1586 fortified Loreto and gave it the privileges of a town; his colossal statue stands on the parvis, above the front steps, a third of the way to the left as one enters. Over the principal doorway there is a lifesize bronze statue of the Virgin and Child by Girolamo Lombardo; the three superb bronze doors executed at the latter end of the 16th century under the reign of Paul V (1605–1621) are also by Lombardo, his sons and his pupils, among them Tiburzio Vergelli, who also made the fine bronze font in the interior. The doors and hanging lamps are by the same artists. The richly decorated campanile (1750 to 1754), by Vanvitelli,[3] is of great height; the principal bell, presented by Leo X in 1516, weighs 11 tons. The interior of the church has mosaics by Domenichino and Guido Reni and other works of art, including statues by Raffaello da Montelupo. In the sacristies on each side of the right transept are frescoes, on the right by Melozzo da Forlì, on the left by Luca Signorelli and in both there are some fine intarsias; the basilica as a whole is thus a collaborative work by generations of architects and artists.

The Santa Casa

Giacobbe Giusti, Basilica of the Holy House

The main attraction of Loreto is the Holy House itself (in Italian, the Santa Casa di Loreto). It has been a Catholicpilgrimage destination since at least the 14th century and a popular tourist destination for non-Catholics as well.

Description

The “house” itself is a plain stone building, 8.5 m by 3.8 m and 4.1 m high; it has a door on the north side and a window on the west; and a niche contains a small black image of the Virgin and Child, in Lebanon cedar, and richly adorned with jewels. Around the house is a tall marble screen designed by Bramante and executed under Popes Leo X, Clement VII and Paul III, by Andrea Sansovino, Girolamo Lombardo, Bandinelli, Guglielmo della Porta and others in the baroque style. The four sides represent the Annunciation, the Nativity, the Arrival of the Santa Casa at Loreto and the Nativity of the Virgin, respectively. The treasury contains a large variety of rich and curious votive offerings. The architectural design is finer than the details of the sculpture. The apse is decorated with 19th-century German frescoes.

Tradition

Giacobbe Giusti, Basilica of the Holy House

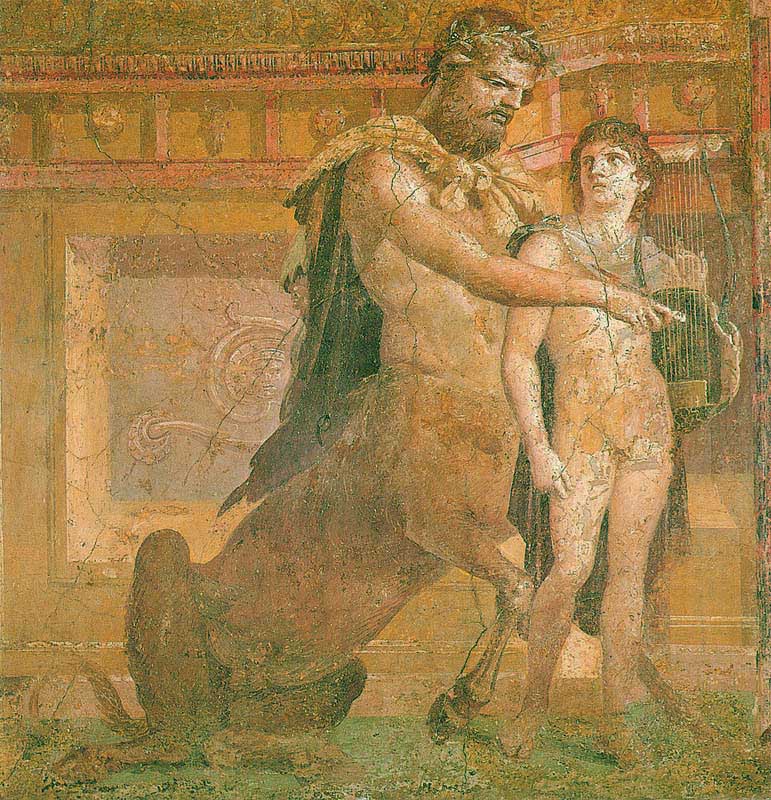

Fresco by Melozzo da Forlì in the sacristy of St Marc

The documented history of the house can only be traced as far back as close of the Crusades, around the 14th century. An early brief reference is made in the Italia Illustrata of Flavius Blondus, secretary to Popes Eugene IV, Nicholas V, Calixtus IIIand Pius II; it is to be read in all its fullness in the Redemptoris mundi Matris Ecclesiæ Lauretana historia, by a certain Teremannus, contained in the Opera Omnia (1576) of Baptista Mantuanus.

The town of has been a popular pilgrimage site since the 13th century[citation needed]. Late medieval religious traditions developed suggesting that this was the house in which the Christian Holy Family (Mary, Joseph and Jesus) had lived when in Judeaat the start of the first millennium c.e., and which was miraculously flown over to Loreto by four angels just before the final expulsion of the Christian Crusaders from the Holy Land in order to protect it from muslim soldiers. According to this narrative, the house at Nazareth in which Mary had been born and brought up, potentially received the Annunciation, and had lived during the Childhood of Christ and after his Ascension, was converted into a church by the Twelve Apostles. In 336, Empress Helena made a pilgrimage to Nazareth and allegedly directed that a basilica be erected over it, in which worship continued until the fall of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. However, there is no firm historical evidence that Helena did in fact make such a intervention.

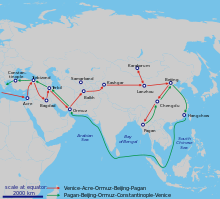

The tale further states that, threatened with destruction by Muslim soldiers, the house was miraculously carried by angels through the air and initially deposited in 1291 on a hill at Tersatto (now Trsat, a suburb of Rijeka, Croatia), where an appearance of the Virgin and numerous miraculous cures attested to its sanctity. These miracles were said to have been confirmed by investigations made at Nazareth by messengers from the governor of Dalmatia. In 1294, angels again carried it across the Adriatic Sea to the woods near Recanati (although the reasoning is not clear as to why this happened); from these woods (Latin lauretum, Italian Colle dei Lauri or from the name of its proprietress Laureta) the chapel derived the name which it still retains (sacellum gloriosæ Virginis in Laureto). From this spot it was afterwards removed to the present hill in 1295, with a slight adjustment being required to fix it in its current site. It is this house that gave the title Our Lady of Loreto sometimes applied to the Virgin; the miracle is occasionally represented in religious art wherein the house is borne by an angelic host.

Bulls in favour of the Shrine at Loreto were issued by Pope Sixtus IV in 1491, and by Julius II in 1507, the last alluding to the translation of the house with some caution (ut pie creditur et fama est). While, like most miracles, the translation of the house is not a matter of faith for Catholics, nonetheless, in the late 17th century, Innocent XIIappointed a missa cum officio proprio (a special Mass) for the Feast of the Translation of the Holy House, which as late as the 20th century was enjoined in the Spanish Breviary as a greater double[jargon] on 10 December 10.

On 4 October 2012, Benedict XVI visited the Shrine to mark the 50th anniversary of John XXIII‘s visit. In his visit, Benedict formally entrusted the World Synod of Bishopsand the Year of Faith to the Virgin of Loreto. [4][5][6]

History

According to Herbert Thurston, in some respects the Lauretan tradition is “beset with difficulties of the gravest kind”, which were noted in a 1906 work on the subject. There are documents which indicate that a church dedicated to the Blessed Virgin already existed at Loreto in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, that is, 180 years before the time of the supposed translation; and there is no mention of the supposed miraculous translation of the Holy House in 1472. Thurston notes that papal confirmations of the Loreto tradition are relatively late (the first Bull mentioning the translation is that of Julius II in 1507), but that they are at first very guarded in expression, for Julius introduces the clause “ut pie creditur et fama est”.[7] Thurston suggests that a miracle-working statue or picture of the Madonna was brought from Tersato in Illyria to Loreto by some pious Christians and was then confounded with the ancient rustic chapel in which it was harboured, the veneration formerly given to the statue afterwards passing to the building.[7]

Finally, he draws comparisons to the shrine at Walsingham, the principal English shrine of the Blessed Virgin, the legend of “Our Lady’s house” (written down about 1465, and consequently earlier than the Loreto translation tradition) supposes that in the time of St. Edward the Confessor a chapel was built at Walsingham, which exactly reproduced the dimensions of the Holy House of Nazareth. When the carpenters could not complete it upon the site that had been chosen, it was transferred and erected by angels’ hands at a spot two hundred feet away.[8]

In modern times, the Church traced the linguistic origins of the story to a local aristocratic family called “Angelos”, which were responsible for the transfer.[9]According to Papal archivist Giuseppe Lapponi, it seems that a family by the name of Angeli saved the bricks of the Holy House from the Muslim invasion. Excavations beneath the House of Loreto found coins, two of which are connected to the Angeli family.[10]

Giacobbe Giusti, Basilica of the Holy House

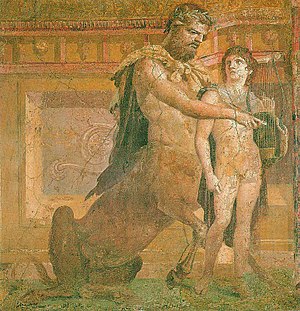

The venerated Marian image of Our Lady of Loreto. The cedar wood was timbered from the Vatican Gardens.

Our Lady of Loreto

Our Lady of Loreto is the title of the Virgin Mary with respect to the Holy House of Loreto. Her statue, carved from Cedar of Lebanon, is a “Black Madonna,” owing to centuries of lamp smoke. It, like the Holy House, is associated with miracles. In the 1600s a Mass and a Marian litany was approved. This “Litany of Loreto” is the Litany of the Blessed Virgin Mary, one of the five litanies approved for public recitation by the Church. In 1920 Pope Benedict XVdeclared the Madonna of Loreto patron saintof air travellers and pilots.[11] The statue was commissioned after a fire in the Santa Casa in 1921 destroyed the original madonna, and it was granted a Canonical Coronation in 1922 by Pope Pius XI. Our Lady of Loreto is commemorated on December 10.

- House of the Virgin Mary

- Giovanni Tonucci

- Territorial prelature of Loreto

- Loreto Church in Warsaw

- Loreta in Prague

- Our Lady of Loreto and St Winefride’s, Kew

References

- ^ Donald Posner – Annibale Carracci a study in the reform of italian painting 1971 “The painting was originally in the basilica of the Santa Casa in Loreto.

- ^ History of Italian Renaissance Art: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture Frederick Hartt, David G. Wilkins – 2010 “Sixtus’s nephews who appears in the group portrait, called Melozzo to Loreto, on the Adriatic coast, to decorate the sacristy of the basilica of the Santa Casa (fig. 14.26). “

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Basilica della Santa Casa”, Fodor’s Archived October 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ “Pope at Marian shrine entrusts Year of Faith, synod to Mary”. Catholic News Service. 4 October 2012. Archived from the original on 5 December 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ Pastoral visit of Benedict XVI to Loreto Archived January 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Benedict XVI, Prayer to Our Lady of Loreto Archived January 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jump up to:a b Thurston, Herbert. “Santa Casa di Loreto.” The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 13. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 10 December 2017

- ^ “The Month”, September 1901

- ^ Kerr, David (4 October 2012). “Pope entrusts Year of Faith, evangelization synod to Mary”. Catholic News Agency. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ Roten SM, Johann. “Our Lady of Loreto and Aviation”, International Marian Research Institute, University of Dayton.

- ^ Donovan, Colin B., “Our Lady of Loreto”, EWTN, August 2, 2005

Bibliography

- Grimaldi, Floriano (1984). La Chiesa di Santa Maria di Loreto nei documenti dei secoli XII – XV (in Italian and Latin). Ancona: Stabilimento Tipografico Mierma.

- Grimaldi, Floriano (1993). La historia della Chiesa di Santa Maria de Loreto (in Italian). Loreto: Carilo.

- Hutchison, William Antony (1863). Loreto and Nazareth: Two Lectures, Containing the Results of Personal Investigation of the Two Sanctuaries. London: E. Dillon.

- Leopardi, Monaldo (1841). La Santa Casa di Loreto: discussioni istoriche e critiche (in Italian). Lugano: presso Francesco Veladini e C.

- Vélez, Karin (2018). The Miraculous Flying House of Loreto: Spreading Catholicism in the Early Modern World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-18449-4.

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). “Santa Casa di Loreto”. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). “Santa Casa di Loreto”. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton.