Giacobbe Giusti, Villa of the Papyri

Giacobbe Giusti, Villa of the Papyri

Giacobbe Giusti, Villa of the Papyri

Giacobbe Giusti, Villa of the Papyri

Giacobbe Giusti, Villa of the Papyri

The Villa of the Papyri (Italian: Villa dei Papiri, also known as Villa dei Pisoni), is named after its unique library of papyri (or scrolls), but is also one of the most luxurious houses in all of Herculaneum and in the Roman world.[1] Its luxury is shown by its exquisite architecture and by the very large number of outstanding works of art discovered, including frescoes, bronzes and marble sculpture[2] which constitute the largest collection of Greek and Roman sculptures ever discovered in a single context.[3]

It is located in the current commune of Ercolano, southern Italy. It was situated on the ancient coastline below the volcano Vesuvius with nothing to obstruct the view of the sea. It was perhaps owned by Julius Caesar‘s father-in-law, Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus.[4]

Plan of Herculaneum and the location of the Villa

In AD 79, the eruption of Vesuvius covered all of Herculaneum with some 30 m of volcanic ash. Herculaneum was first excavated in the years between 1750 and 1765 by Karl Weber by means of underground tunnels. The villa’s name derives from the discovery of its library, the only surviving library from the Graeco-Roman world that exists in its entirety.[5] It contained over 1,800 papyrus scrolls, now carbonised by the heat of the eruption, the “Herculaneum papyri“.

Most of the villa is still underground, but parts have been cleared of volcanic deposits. Many of the finds are displayed in the Naples National Archaeological Museum.

The Getty Villa is a reproduction of the Villa of the Papyri.

Layout

Ground Plan showing location of tunnels(brown)

Drunken Satyr, villa dei papiri

Aeschines, villa dei papiri, museo archeologico, Napoli

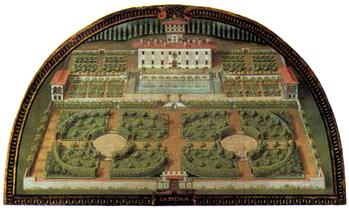

Sited a few hundred metres from the nearest house in Herculaneum, the villa’s front stretched for more than 250 m along the coastline of the Gulf of Naples. It was surrounded by a garden closed off by porticoes, but with an ample stretch of gardens, vineyards and woods down to a small harbour.

It has recently been ascertained that the height of the main floor in antiquity was no less than 16 metres above sea level, and the villa had four architectural levels underneath the main floor, arranged in terrasses overlooking the sea.[6]

The villa’s layout is faithful to, but enlarges upon, the architectural scheme of suburban villas in the country around Pompeii. The atrium functioned as an entrance hall and a means of communication with the various parts of the house. The entrance opened with a columned portico on the sea side.

The first peristyle had 10 columns on each side and a swimming pool in the centre. In this enclosure were found the bronze herma of Doryphorus, a replica of Polykleitos‘ athlete, and the herma of an Amazon made by Apollonios son of Archias of Athens.[7] The large second peristyle could be reached by passing through a large tablinum in which, under a propylaeum, was the archaic statue of Athena Promachos. A collection of bronze busts were in the interior of the tablinum. These included the head of Scipio Africanus.[1]

Dancers, da villa dei papiri, peristilio quadrato

The living and reception quarters were grouped around the porticoes and terraces, giving occupants ample sunlight and a view of the countryside and sea. In the living quarters, bath installations were brought to light, and the library of rolled and carbonised papyri placed inside wooden capsae, some of them on ordinary wooden shelves and around the walls and some on the two sides of a set of shelves in the middle of the room.[1]

The grounds included a large area of covered and uncovered gardens for walks in the shade or in the warmth of the sun. The gardens included a gallery of busts, hermae and small marble and bronze statues. These were laid out between columns amid the open part of the garden and on the edges of the large swimming bath.[1]

Ptolemy Apion

Works of Art

The luxury of the villa is evidenced not only by the many works of art, but especially by the large number of rare bronze statues found there, all masterpieces. The villa housed a collection of at least 80 sculptures of magnificent quality,[8] many now conserved in the Naples National Archaeological Museum.[1] Among them is the bronze Seated Hermes, found at the villa in 1758. Around the bowl of the atrium impluvium were 11 bronze fountain statues depicting Satyrs pouring water from a pitcher and Amorini pouring water from the mouth of a dolphin. Other statues and busts were found in the corners around the atrium walls.[1]

Five statues of life-sized bronze dancing women wearing the Doric peplos sculpted in different positions and with inlaid eyes are adapted Roman copies of originals from the fifth century BC. They are also hydrophorai drawing water from a fountain.

Epicureanism and the library

The owner of the house, perhaps Calpurnius Piso, established a library of a mainly philosophical character. It is believed that the library might have been collected and selected by Piso’s family friend and client, the Epicurean Philodemus of Gàdara – although his conclusion is not certain[4][9] Followers of Epicurus studied the teachings of this moral and natural philosopher. This philosophy taught that man is mortal, that the cosmos is the result of accident, that there is no providential god, and that the criteria of a good life are pleasure and temperance. Philodemus’ connections with Piso brought him an opportunity to influence the young students of Greek literature and philosophy who gathered around him at Herculaneum and Naples. Much of his work was discovered in about a thousand papyrus rolls in the philosophical library recovered at Herculaneum. Although his prose work is detailed in the strung-out, non-periodic style typical of Hellenistic Greek prose before the revival of the Attic style after Cicero, Philodemus surpassed the average literary standard to which most epicureans aspired. Philodemus succeeded in influencing the most learned and distinguished Romans of his age. None of his prose work was known until the rolls of papyri were discovered among the ruins of the Villa of the Papyri.[4]

Papyrus recovered from Villa of the Papyri.[1]

At the time of the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79, the valuable library was packed in cases ready to be moved to safety when it was overtaken by pyroclastic flow; the eruption eventually deposited some 20–25 m of volcanic ash over the site, charring the scrolls but preserving them— the only surviving library of Antiquity— as the ash hardened to form tuff.[1]

Excavation

The Bourbon excavations were halted in 1765 due to complaints from the residents living above. The exact location of the villa was then lost for two centuries.[10] In the 1980s work on re-discovering the villa began by studying 18th century documentation on entrances to the tunnels and in 1986 the breakthrough was made through an ancient well. The backfill from some of the tunnels was cleared to allow re-exploration of the villa when it was found that the parts of the villa that survived the Bourbon robbers were still remarkable in quantity and quality.

Excavation to expose part of the villa was done in the 1990s and revealed two previously undiscovered lower floors to the villa[11] with frescoes in situ. These were found along the southwest-facing terrace of about 4 metres height. The first row of rooms lying below the arcade was eveidenced by a series of rectangular openings along the façade.

Limited excavations recommenced at the site in 2007 to preserve the remains when beautifully carved parts of wood and ivory furniture were discovered. Since then limited public access became available.

As of 2012, there are still 2,800 m² left to be excavated of the villa. The remainder of the site has not been excavated because the Italian government is preferring conservation to excavation, and protecting what has already been uncovered.[12] David Woodley Packard, who has funded conservation work at Herculaneum through his Packard Humanities Institute, has said that he is likely to be able to fund excavation of the Villa of the Papyri when the authorities agree to it; but no work will be permitted on the site until the completion of a feasibility report, which has been in preparation for some years. The first part of the report emerged in 2008 but included no timetable or cost projections, since the decision for further excavation is a political one.[13] Politics involve excavation under inhabited areas in addition to unspecified but reported[14] references to mafia involvement.

Using multi-spectral imaging, a technique developed in the early 1990s, it is possible to read the burned papyri. With multi-spectral imaging, many pictures of the illegible papyri are taken using different filters in the infrared or in the ultraviolet range, finely tuned to capture certain wavelengths of light. Thus, the optimum spectral portion can be found for distinguishing ink from paper on the blackened papyrus surface.

Non-destructive CT scans will, it is hoped, provide breakthroughs in reading the fragile unopened scrolls without destroying them in the process. Encouraging results along this line of research have been obtained, which use Phase-contrast X-ray imaging. [15] [16] [17] [18] According to authors, “this pioneering research opens up new prospects not only for the many papyri still unopened, but also for others that have not yet been discovered, perhaps including a second library of Latin papyri at a lower, as yet unexcavated level of the Villa.”[19]

J. Paul Getty Museum

Bronze bust of Scipio Africanus, mid 1st century BC, found in the Villa of the Papyri

The original “Getty Villa“, part of the J. Paul Getty Museum complex at Pacific Palisades, California is a free replication of the Villa of the Papyri, as it was published in Le Antichità di Ercolano. This museum building was constructed in the early 1970s by the architectural firm of Langdon and Wilson. Architectural consultant Norman Neuerburg and Getty’s curator of antiquities Jiří Frel worked closely with J. Paul Getty to develop the interior and exterior details. Since the Villa of the Papyri was buried by the eruption and much of it remains unexcavated, Neuerburg based many of the villa’s architectural and landscaping details on elements from other ancient Roman houses in the towns of Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Stabiae.[20]

With the move of the Museum to the Getty Center, the “Getty Villa” as it is now called, was renovated; it reopened on January 28, 2006.

In modern literature

Several scenes in Robert Harris‘ bestselling novel Pompeii are set in the Villa of the Papyri, just before the eruption engulfed it. The villa is mentioned as belonging to Roman aristocrat Pedius Cascus and his wife Rectina. (Pliny the Younger mentions Rectina, whom he calls the wife of Tascius, in Letter 16 of book VI of his Letters.) At the start of the eruption Rectina prepares to have the library evacuated and sends urgent word to her old friend, Pliny the Elder, who commands the Roman Navy at Misenum on the other side of the Bay of Naples. Pliny immediately sets out in a warship, and gets in sight of the villa, but the eruption prevents him from landing and taking off Rectina and her library — which is thus left for modern archaeologists to find.

Sculpture from the Villa