Giacobbe Giusti, Quintus Horatius Flaccus, Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus

Ausschnitt aus dem Fresko Der Parnass von Raffael, ca. 1508–1511 gemalt. Die vorne stehende männliche Figur wird als Horaz gedeutet.

Giacobbe Giusti, Quintus Horatius Flaccus, Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus

Horace in his Studium: German print of the fifteenth century, summarizing the final ode 4.15 (in praise of Augustus).

Giacobbe Giusti, Quintus Horatius Flaccus, Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus

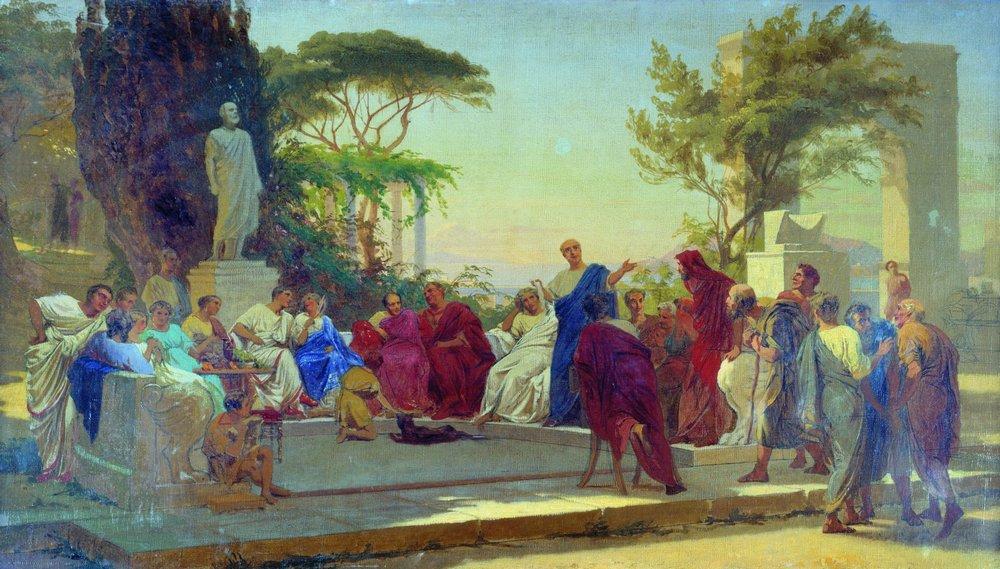

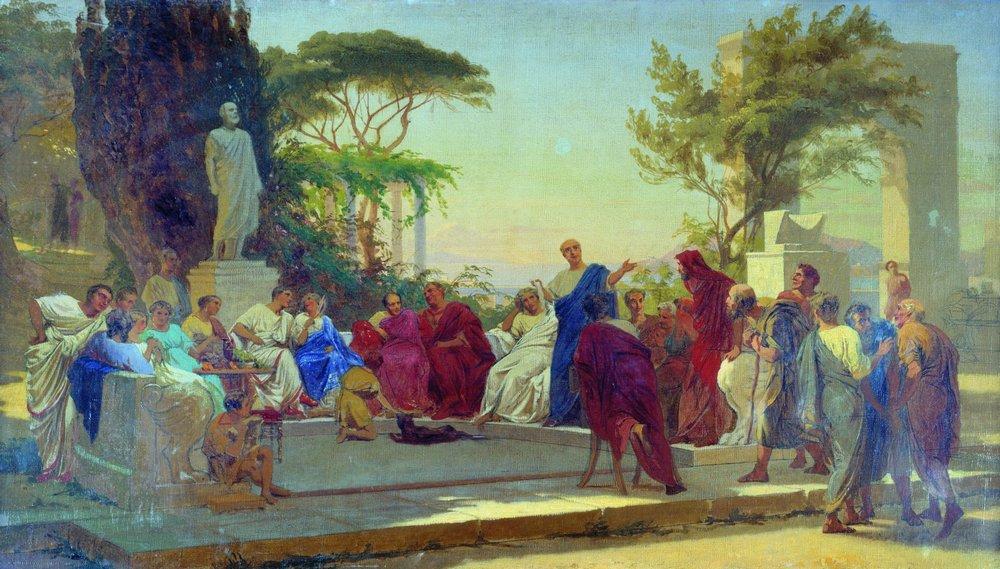

Horace reads before Maecenas, by Fyodor Bronnikov

Giacobbe Giusti, Quintus Horatius Flaccus, Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus

A poem of the Roman lyric poet Horace on a wall of the building at the Cleveringaplaats 1, Leiden, The Netherlands

Giacobbe Giusti, Quintus Horatius Flaccus, Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus

Ernst Fries, Blick in die Sabinerberge östlich von Licenza, Öl auf Mahagoni, 1827

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (December 8, 65 BC – November 27, 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilianregarded his Odes as just about the only Latin lyrics worth reading: “He can be lofty sometimes, yet he is also full of charm and grace, versatile in his figures, and felicitously daring in his choice of words.”[nb 1]

Horace also crafted elegant hexameter verses (Satires and Epistles) and caustic iambic poetry (Epodes). The hexameters are amusing yet serious works, friendly in tone, leading the ancient satirist Persius to comment: “as his friend laughs, Horace slyly puts his finger on his every fault; once let in, he plays about the heartstrings”.[nb 2]

His career coincided with Rome’s momentous change from a republicto an empire. An officer in the republican army defeated at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC, he was befriended by Octavian’s right-hand man in civil affairs, Maecenas, and became a spokesman for the new regime. For some commentators, his association with the regime was a delicate balance in which he maintained a strong measure of independence (he was “a master of the graceful sidestep”)[1] but for others he was, in John Dryden‘s phrase, “a well-mannered court slave”.[2][nb 3]

Life

Giacobbe Giusti, Quintus Horatius Flaccus, Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus

Horatii Flacci Sermonum (1577)

Horace can be regarded as the world’s first autobiographer[3] – In his writings, he tells us far more about himself, his character, his development, and his way of life than any other great poet in antiquity. Some of the biographical writings contained in his writings can be supplemented from the short but valuable “Life of Horace” by Suetonius (in his Lives of the Poets).[4]

Childhood

He was born on 8 December 65 BC[nb 4] in the Samnite south of Italy.[5] His home town, Venusia, lay on a trade route in the border region between Apulia and Lucania(Basilicata). Various Italic dialects were spoken in the area and this perhaps enriched his feeling for language. He could have been familiar with Greek words even as a young boy and later he poked fun at the jargon of mixed Greek and Oscan spoken in neighbouring Canusium.[6] One of the works he probably studied in school was the Odyssia of Livius Andronicus, taught by teachers like the ‘Orbilius‘ mentioned in one of his poems.[7] Army veterans could have been settled there at the expense of local families uprooted by Rome as punishment for their part in the Social War (91–88 BC).[8] Such state-sponsored migration must have added still more linguistic variety to the area. According to a local tradition reported by Horace,[9] a colony of Romans or Latins had been installed in Venusia after the Samniteshad been driven out early in the third century. In that case, young Horace could have felt himself to be a Roman[10][11] though there are also indications that he regarded himself as a Samnite or Sabellus by birth.[12][13] Italians in modern and ancient times have always been devoted to their home towns, even after success in the wider world, and Horace was no different. Images of his childhood setting and references to it are found throughout his poems.[14]

Horace’s father was probably a Venutian taken captive by Romans in the Social War, or possibly he was descended from a Sabine captured in the Samnite Wars. Either way, he was a slave for at least part of his life. He was evidently a man of strong abilities however and managed to gain his freedom and improve his social position. Thus Horace claimed to be the free-born son of a prosperous ‘coactor’.[15] The term ‘coactor’ could denote various roles, such as tax collector, but its use by Horace[16] was explained by scholia as a reference to ‘coactor argentareus’ i.e. an auctioneer with some of the functions of a banker, paying the seller out of his own funds and later recovering the sum with interest from the buyer.[17]

The father spent a small fortune on his son’s education, eventually accompanying him to Rome to oversee his schooling and moral development. The poet later paid tribute to him in a poem[18] that one modern scholar considers the best memorial by any son to his father.[nb 5] The poem includes this passage:

If my character is flawed by a few minor faults, but is otherwise decent and moral, if you can point out only a few scattered blemishes on an otherwise immaculate surface, if no one can accuse me of greed, or of prurience, or of profligacy, if I live a virtuous life, free of defilement (pardon, for a moment, my self-praise), and if I am to my friends a good friend, my father deserves all the credit… As it is now, he deserves from me unstinting gratitude and praise. I could never be ashamed of such a father, nor do I feel any need, as many people do, to apologize for being a freedman’s son. Satires 1.6.65–92

He never mentioned his mother in his verses and he might not have known much about her. Perhaps she also had been a slave.[15]

Adulthood

Horace left Rome, possibly after his father’s death, and continued his formal education in Athens, a great centre of learning in the ancient world, where he arrived at nineteen years of age, enrolling in The Academy. Founded by Plato, The Academy was now dominated by Epicureans and Stoics, whose theories and practises made a deep impression on the young man from Venusia.[19] Meanwhile, he mixed and lounged about with the elite of Roman youth, such as Marcus, the idle son of Cicero, and the Pompeius to whom he later addressed a poem.[20] It was in Athens too that he probably acquired deep familiarity with the ancient tradition of Greek lyric poetry, at that time largely the preserve of grammarians and academic specialists (access to such material was easier in Athens than in Rome, where the public libraries had yet to be built by Asinius Pollio and Augustus).[21]

Rome’s troubles following the assassination of Julius Caesar were soon to catch up with him. Marcus Junius Brutus came to Athens seeking support for the republican cause. Brutus was fêted around town in grand receptions and he made a point of attending academic lectures, all the while recruiting supporters among the young men studying there, including Horace.[22] An educated young Roman could begin military service high in the ranks and Horace was made tribunus militum (one of six senior officers of a typical legion), a post usually reserved for men of senatorial or equestrian rank and which seems to have inspired jealousy among his well-born confederates.[23][24] He learned the basics of military life while on the march, particularly in the wilds of northern Greece, whose rugged scenery became a backdrop to some of his later poems.[25] It was there in 42 BC that Octavian(later Augustus) and his associate Mark Antony crushed the republican forces at the Battle of Philippi. Horace later recorded it as a day of embarrassment for himself, when he fled without his shield,[26]but allowance should be made for his self-deprecating humour. Moreover, the incident allowed him to identify himself with some famous poets who had long ago abandoned their shields in battle, notably his heroes Alcaeus and Archilochus. The comparison with the latter poet is uncanny: Archilochus lost his shield in a part of Thrace near Philippi, and he was deeply involved in the Greek colonization of Thasos, where Horace’s die-hard comrades finally surrendered.[24]

Octavian offered an early amnesty to his opponents and Horace quickly accepted it. On returning to Italy, he was confronted with yet another loss: his father’s estate in Venusia was one of many throughout Italy to be confiscated for the settlement of veterans (Virgillost his estate in the north about the same time). Horace later claimed that he was reduced to poverty and this led him to try his hand at poetry.[27] In reality, there was no money to be had from versifying. At best, it offered future prospects through contacts with other poets and their patrons among the rich.[28] Meanwhile, he obtained the sinecure of scriba quaestorius, a civil service position at the aerarium or Treasury, profitable enough to be purchased even by members of the ordo equester and not very demanding in its work-load, since tasks could be delegated to scribae or permanent clerks.[29] It was about this time that he began writing his Satires and Epodes.

Poet

Giacobbe Giusti, Quintus Horatius Flaccus, Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus

The Epodes belong to iambic poetry. Iambic poetry features insulting and obscene language;[30][31] sometimes, it is referred to as blame poetry.[32] Blame poetry, or shame poetry, is poetry written to blame and shame fellow citizens into a sense of their social obligations. Horace modelled these poems on the poetry of Archilochus. Social bonds in Rome had been decaying since the destruction of Carthage a little more than a hundred years earlier, due to the vast wealth that could be gained by plunder and corruption.[33]These social ills were magnified by rivalry between Julius Caesar, Mark Antony and confederates like Sextus Pompey, all jockeying for a bigger share of the spoils. One modern scholar has counted a dozen civil wars in the hundred years leading up to 31 BC, including the Spartacus rebellion, eight years before Horace’s birth.[34] As the heirs to Hellenistic culture, Horace and his fellow Romans were not well prepared to deal with these problems:

At bottom, all the problems that the times were stirring up were of a social nature, which the Hellenistic thinkers were ill qualified to grapple with. Some of them censured oppression of the poor by the rich, but they gave no practical lead, though they may have hoped to see well-meaning rulers doing so. Philosophy was drifting into absorption in self, a quest for private contentedness, to be achieved by self-control and restraint, without much regard for the fate of a disintegrating community.

Horace’s Hellenistic background is clear in his Satires, even though the genre was unique to Latin literature. He brought to it a style and outlook suited to the social and ethical issues confronting Rome but he changed its role from public, social engagement to private meditation.[36] Meanwhile, he was beginning to interest Octavian’s supporters, a gradual process described by him in one of his satires.[18] The way was opened for him by his friend, the poet Virgil, who had gained admission into the privileged circle around Maecenas, Octavian’s lieutenant, following the success of his Eclogues. An introduction soon followed and, after a discreet interval, Horace too was accepted. He depicted the process as an honourable one, based on merit and mutual respect, eventually leading to true friendship, and there is reason to believe that his relationship was genuinely friendly, not just with Maecenas but afterwards with Augustus as well.[37] On the other hand, the poet has been unsympathetically described by one scholar as “a sharp and rising young man, with an eye to the main chance.”[38] There were advantages on both sides: Horace gained encouragement and material support, the politicians gained a hold on a potential dissident.[39] His republican sympathies, and his role at Philippi, may have caused him some pangs of remorse over his new status. However most Romans considered the civil wars to be the result of contentio dignitatis, or rivalry between the foremost families of the city, and he too seems to have accepted the principate as Rome’s last hope for much needed peace.[40]

In 37 BC, Horace accompanied Maecenas on a journey to Brundisium, described in one of his poems[41] as a series of amusing incidents and charming encounters with other friends along the way, such as Virgil. In fact the journey was political in its motivation, with Maecenas en route to negotiatie the Treaty of Tarentum with Antony, a fact Horace artfully keeps from the reader (political issues are largely avoided in the first book of satires).[39] Horace was probably also with Maecenas on one of Octavian’s naval expeditions against the piratical Sextus Pompeius, which ended in a disastrous storm off Palinurus in 36 BC, briefly alluded to by Horace in terms of near-drowning.[42][nb 6] There are also some indications in his verses that he was with Maecenas at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, where Octavian defeated his great rival, Antony.[43][nb 7] By then Horace had already received from Maecenas the famous gift of his Sabine farm, probably not long after the publication of the first book of Satires. The gift, which included income from five tenants, may have ended his career at the Treasury, or at least allowed him to give it less time and energy.[44] It signalled his identification with the Octavian regime yet, in the second book of Satires that soon followed, he continued the apolitical stance of the first book. By this time, he had attained the status of eques Romanus,[45] perhaps as a result of his work at the Treasury.[46]

Knight

Odes 1–3 were the next focus for his artistic creativity. He adapted their forms and themes from Greek lyric poetry of the seventh and sixth centuries BC. The fragmented nature of the Greek world had enabled his literary heroes to express themselves freely and his semi-retirement from the Treasury in Rome to his own estate in the Sabine hills perhaps empowered him to some extent also[47] yet even when his lyrics touched on public affairs they reinforced the importance of private life.[1] Nevertheless, his work in the period 30–27 BC began to show his closeness to the regime and his sensitivity to its developing ideology. In Odes 1.2, for example, he eulogized Octavian in hyperboles that echo Hellenistic court poetry. The name Augustus, which Octavian assumed in January 27 BC, is first attested in Odes3.3 and 3.5. In the period 27–24 BC, political allusions in the Odesconcentrated on foreign wars in Britain (1.35), Arabia (1.29) Spain (3.8) and Parthia (2.2). He greeted Augustus on his return to Rome in 24 BC as a beloved ruler upon whose good health he depended for his own happiness (3.14).[48]

The public reception of Odes 1–3 disappointed him however. He attributed the lack of success to jealousy among imperial courtiers and to his isolation from literary cliques.[49] Perhaps it was disappointment that led him to put aside the genre in favour of verse letters. He addressed his first book of Epistles to a variety of friends and acquaintances in an urbane style reflecting his new social status as a knight. In the opening poem, he professed a deeper interest in moral philosophy than poetry[50] but, though the collection demonstrates a leaning towards stoic theory, it reveals no sustained thinking about ethics.[51] Maecenas was still the dominant confidante but Horace had now begun to assert his own independence, suavely declining constant invitations to attend his patron.[52] In the final poem of the first book of Epistles, he revealed himself to be forty-four years old in the consulship of Lollius and Lepidus i.e. 21 BC, and “of small stature, fond of the sun, prematurely grey, quick-tempered but easily placated”.[53][54]

According to Suetonius, the second book of Epistles was prompted by Augustus, who desired a verse epistle to be addressed to himself. Augustus was in fact a prolific letter-writer and he once asked Horace to be his personal secretary. Horace refused the secretarial role but complied with the emperor’s request for a verse letter.[55] The letter to Augustus may have been slow in coming, being published possibly as late as 11 BC. It celebrated, among other things, the 15 BC military victories of his stepsons, Drusus and Tiberius, yet it and the following letter[56] were largely devoted to literary theory and criticism. The literary theme was explored still further in Ars Poetica, published separately but written in the form of an epistle and sometimes referred to as Epistles 2.3 (possibly the last poem he ever wrote).[57] He was also commissioned to write odes commemorating the victories of Drusus and Tiberius[58] and one to be sung in a temple of Apollo for the Secular Games, a long abandoned festival that Augustus revived in accordance with his policy of recreating ancient customs (Carmen Saeculare).

Suetonius recorded some gossip about Horace’s sexual activities late in life, claiming that the walls of his bedchamber were covered with obscene pictures and mirrors, so that he saw erotica wherever he looked.[nb 8] The poet died at 56 years of age, not long after his friend Maecenas, near whose tomb he was laid to rest. Both men bequeathed their property to Augustus, an honour that the emperor expected of his friends.[59]

Works

Giacobbe Giusti, Quintus Horatius Flaccus, Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus

The dating of Horace’s works isn’t known precisely and scholars often debate the exact order in which they were first ‘published’. There are persuasive arguments for the following chronology:[60]

Historical context

Horace composed in traditional metres borrowed from Archaic Greece, employing hexameters in his Satires and Epistles, and iambs in his Epodes, all of which were relatively easy to adapt into Latin forms. His Odes featured more complex measures, including alcaics and sapphics, which were sometimes a difficult fit for Latin structure and syntax. Despite these traditional metres, he presented himself as a partisan in the development of a new and sophisticated style. He was influenced in particular by Hellenistic aesthetics of brevity, elegance and polish, as modeled in the work of Callimachus.[61]

As soon as Horace, stirred by his own genius and encouraged by the example of Virgil, Varius, and perhaps some other poets of the same generation, had determined to make his fame as a poet, being by temperament a fighter, he wanted to fight against all kinds of prejudice, amateurish slovenliness, philistinism, reactionary tendencies, in short to fight for the new and noble type of poetry which he and his friends were endeavouring to bring about.

In modern literary theory, a distinction is often made between immediate personal experience (Urerlebnis) and experience mediated by cultural vectors such as literature, philosophy and the visual arts (Bildungserlebnis).[63] The distinction has little relevance for Horace[citation needed] however since his personal and literary experiences are implicated in each other. Satires 1.5, for example, recounts in detail a real trip Horace made with Virgil and some of his other literary friends, and which parallels a Satire by Lucilius, his predecessor.[64] Unlike much Hellenistic-inspired literature, however, his poetry was not composed for a small coterie of admirers and fellow poets, nor does it rely on abstruse allusions for many of its effects. Though elitist in its literary standards, it was written for a wide audience, as a public form of art.[65] Ambivalence also characterizes his literary persona, since his presentation of himself as part of a small community of philosophically aware people, seeking true peace of mind while shunning vices like greed, was well adapted to Augustus’s plans to reform public morality, corrupted by greed – his personal plea for moderation was part of the emperor’s grand message to the nation.[66]

Horace generally followed the examples of poets established as classics in different genres, such as Archilochus in the Epodes, Lucilius in the Satires and Alcaeus in the Odes, later broadening his scope for the sake of variation and because his models weren’t actually suited to the realities confronting him. Archilochus and Alcaeus were aristocratic Greeks whose poetry had a social and religious function that was immediately intelligible to their audiences but which became a mere artifice or literary motif when transposed to Rome. However, the artifice of the Odes is also integral to their success, since they could now accommodate a wide range of emotional effects, and the blend of Greek and Roman elements adds a sense of detachment and universality.[67] Horace proudly claimed to introduce into Latin the spirit and iambic poetry of Archilochus but (unlike Archilochus) without persecuting anyone (Epistles 1.19.23–5). It was no idle boast. His Epodes were modeled on the verses of the Greek poet, as ‘blame poetry’, yet he avoided targeting real scapegoats. Whereas Archilochus presented himself as a serious and vigorous opponent of wrong-doers, Horace aimed for comic effects and adopted the persona of a weak and ineffectual critic of his times (as symbolized for example in his surrender to the witch Canidia in the final epode).[68] He also claimed to be the first to introduce into Latin the lyrical methods of Alcaeus (Epistles 1.19.32–3) and he actually was the first Latin poet to make consistent use of Alcaic meters and themes: love, politics and the symposium. He imitated other Greek lyric poets as well, employing a ‘motto’ technique, beginning each ode with some reference to a Greek original and then diverging from it.[69]

The satirical poet Lucilius was a senator’s son who could castigate his peers with impunity. Horace was a mere freedman’s son who had to tread carefully.[70] Lucilius was a rugged patriot and a significant voice in Roman self-awareness, endearing himself to his countrymen by his blunt frankness and explicit politics. His work expressed genuine freedom or libertas. His style included ‘metrical vandalism’ and looseness of structure. Horace instead adopted an oblique and ironic style of satire, ridiculing stock characters and anonymous targets. His libertas was the private freedom of a philosophical outlook, not a political or social privilege.[71] His Satires are relatively easy-going in their use of meter (relative to the tight lyric meters of the Odes)[72] but formal and highly controlled relative to the poems of Lucilius, whom Horace mocked for his sloppy standards (Satires 1.10.56–61)[nb 12]

The Epistles may be considered among Horace’s most innovative works. There was nothing like it in Greek or Roman literature. Occasionally poems had had some resemblance to letters, including an elegiac poem from Solon to Mimnermus and some lyrical poems from Pindar to Hieron of Syracuse. Lucilius had composed a satire in the form of a letter, and some epistolary poems were composed by Catullus and Propertius. But nobody before Horace had ever composed an entire collection of verse letters,[73] let alone letters with a focus on philosophical problems. The sophisticated and flexible style that he had developed in his Satires was adapted to the more serious needs of this new genre.[74] Such refinement of style was not unusual for Horace. His craftsmanship as a wordsmith is apparent even in his earliest attempts at this or that kind of poetry, but his handling of each genre tended to improve over time as he adapted it to his own needs.[70] Thus for example it is generally agreed that his second book of Satires, where human folly is revealed through dialogue between characters, is superior to the first, where he propounds his ethics in monologues. Nevertheless, the first book includes some of his most popular poems.[75]

Themes

Horace developed a number of inter-related themes throughout his poetic career, including politics, love, philosophy and ethics, his own social role, as well as poetry itself. His Epodes and Satires are forms of ‘blame poetry’ and both have a natural affinity with the moralising and diatribes of Cynicism. This often takes the form of allusions to the work and philosophy of Bion of Borysthenes [nb 13] but it is as much a literary game as a philosophical alignment. By the time he composed his Epistles, he was a critic of Cynicism along with all impractical and “high-falutin” philosophy in general.[nb 14][76] The Satires also include a strong element of Epicureanism, with frequent allusions to the Epicurean poet Lucretius.[nb 15] So for example the Epicurean sentiment carpe diem is the inspiration behind Horace’s repeated punning on his own name (Horatius ~ hora) in Satires 2.6.[77] The Satires also feature some Stoic, Peripatetic and Platonic (Dialogues) elements. In short, the Satires present a medley of philosophical programs, dished up in no particular order – a style of argument typical of the genre.[78] The Odes display a wide range of topics. Over time, he becomes more confident about his political voice.[79] Although he is often thought of as an overly intellectual lover, he is ingenuous in representing passion.[80] The “Odes” weave various philosophical strands together, with allusions and statements of doctrine present in about a third of the Odes Books 1–3, ranging from the flippant (1.22, 3.28) to the solemn (2.10, 3.2, 3.3). Epicureanism is the dominant influence, characterizing about twice as many of these odes as Stoicism. A group of odes combines these two influences in tense relationships, such as Odes 1.7, praising Stoic virility and devotion to public duty while also advocating private pleasures among friends. While generally favouring the Epicurean lifestyle, the lyric poet is as eclectic as the satiric poet, and in Odes 2.10 even proposes Aristotle’s golden mean as a remedy for Rome’s political troubles.[81] Many of Horace’s poems also contain much reflection on genre, the lyric tradition, and the function of poetry.[82] Odes 4, thought to be composed at the emperor’s request, takes the themes of the first three books of “Odes” to a new level. This book shows greater poetic confidence after the public performance of his “Carmen saeculare” or “Century hymn” at a public festival orchestrated by Augustus. In it, Horace addresses the emperor Augustus directly with more confidence and proclaims his power to grant poetic immortality to those he praises. It is the least philosophical collection of his verses, excepting the twelfth ode, addressed to the dead Virgil as if he were living. In that ode, the epic poet and the lyric poet are aligned with Stoicism and Epicureanism respectively, in a mood of bitter-sweet pathos.[83] The first poem of the Epistles sets the philosophical tone for the rest of the collection: “So now I put aside both verses and all those other games: What is true and what befits is my care, this my question, this my whole concern.” His poetic renunciation of poetry in favour of philosophy is intended to be ambiguous. Ambiguity is the hallmark of the Epistles. It is uncertain if those being addressed by the self-mocking poet-philosopher are being honoured or criticized. Though he emerges as an Epicurean, it is on the understanding that philosophical preferences, like political and social choices, are a matter of personal taste. Thus he depicts the ups and downs of the philosophical life more realistically than do most philosophers.[84]

Reception

Giacobbe Giusti, Quintus Horatius Flaccus, Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus

The reception of Horace’s work has varied from one epoch to another and varied markedly even in his own lifetime. Odes 1–3 were not well received when first ‘published’ in Rome, yet Augustus later commissioned a ceremonial ode for the Centennial Games in 17 BC and also encouraged the publication of Odes 4, after which Horace’s reputation as Rome’s premier lyricist was assured. His Odes were to become the best received of all his poems in ancient times, acquiring a classic status that discouraged imitation: no other poet produced a comparable body of lyrics in the four centuries that followed[85] (though that might also be attributed to social causes, particularly the parasitism that Italy was sinking into).[86] In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, ode-writing became highly fashionable in England and a large number of aspiring poets imitated Horace both in English and in Latin.[87]

In a verse epistle to Augustus (Epistle 2.1), in 12 BC, Horace argued for classic status to be awarded to contemporary poets, including Virgil and apparently himself.[88] In the final poem of his third book of Odes he claimed to have created for himself a monument more durable than bronze (“Exegi monumentum aere perennius”, Carmina 3.30.1). For one modern scholar, however, Horace’s personal qualities are more notable than the monumental quality of his achievement:

…when we hear his name we don’t really think of a monument. We think rather of a voice which varies in tone and resonance but is always recognizable, and which by its unsentimental humanity evokes a very special blend of liking and respect.

Yet for men like Wilfred Owen, scarred by experiences of World War I, his poetry stood for discredited values:

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The Old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.[nb 16]

The same motto, Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori, had been adapted to the ethos of martyrdom in the lyrics of early Christian poets like Prudentius.[90]

These preliminary comments touch on a small sample of developments in the reception of Horace’s work. More developments are covered epoch by epoch in the following sections.

Antiquity

Horace’s influence can be observed in the work of his near contemporaries, Ovid and Propertius. Ovid followed his example in creating a completely natural style of expression in hexameter verse, and Propertius cheekily mimicked him in his third book of elegies.[nb 17] His Epistles provided them both with a model for their own verse letters and it also shaped Ovid’s exile poetry.[nb 18]

His influence had a perverse aspect. As mentioned before, the brilliance of his Odes may have discouraged imitation. Conversely, they may have created a vogue for the lyrics of the archaic Greek poet Pindar, due to the fact that Horace had neglected that style of lyric (see Pindar#Influence and legacy).[91] The iambic genre seems almost to have disappeared after publication of Horace’s Epodes. Ovid’s Ibiswas a rare attempt at the form but it was inspired mainly by Callimachus, and there are some iambic elements in Martial but the main influence there was Catullus.[92] A revival of popular interest in the satires of Lucilius may have been inspired by Horace’s criticism of his unpolished style. Both Horace and Lucilius were considered good role-models by Persius, who critiqued his own satires as lacking both the acerbity of Lucillius and the gentler touch of Horace.[nb 19]Juvenal‘s caustic satire was influenced mainly by Lucilius but Horace by then was a school classic and Juvenal could refer to him respectfully and in a round-about way as “the Venusine lamp“.[nb 20]

Statius paid homage to Horace by composing one poem in Sapphic and one in Alcaic meter (the verse forms most often associated with Odes), which he included in his collection of occasional poems, Silvae. Ancient scholars wrote commentaries on the lyric meters of the Odes, including the scholarly poet Caesius Bassus. By a process called derivatio, he varied established meters through the addition or omission of syllables, a technique borrowed by Seneca the Youngerwhen adapting Horatian meters to the stage.[93]

Horace’s poems continued to be school texts into late antiquity. Works attributed to Helenius Acro and Pomponius Porphyrio are the remnants of a much larger body of Horatian scholarship. Porphyrio arranged the poems in non-chronological order, beginning with the Odes, because of their general popularity and their appeal to scholars (the Odes were to retain this privileged position in the medieval manuscript tradition and thus in modern editions also). Horace was often evoked by poets of the fourth century, such as Ausonius and Claudian. Prudentius presented himself as a Christian Horace, adapting Horatian meters to his own poetry and giving Horatian motifs a Christian tone.[nb 21] On the other hand, St Jerome, modelled an uncompromising response to the pagan Horace, observing: “What harmony can there be between Christ and the Devil? What has Horace to do with the Psalter?“[nb 22] By the early sixth century, Horace and Prudentius were both part of a classical heritage that was struggling to survive the disorder of the times. Boethius, the last major author of classical Latin literature, could still take inspiration from Horace, sometimes mediated by Senecan tragedy.[94] It can be argued that Horace’s influence extended beyond poetry to dignify core themes and values of the early Christian era, such as self-sufficiency, inner contentment and courage.[nb 23]

Middle Ages and Renaissance

Giacobbe Giusti, Quintus Horatius Flaccus, Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus

Horace in his Studium: German print of the fifteenth century, summarizing the final ode 4.15 (in praise of Augustus).

Classical texts almost ceased being copied in the period between the mid sixth century and the Carolingian revival. Horace’s work probably survived in just two or three books imported into northern Europe from Italy. These became the ancestors of six extant manuscripts dated to the ninth century. Two of those six manuscripts are French in origin, one was produced in Alsace, and the other three show Irish influence but were probably written in continental monasteries (Lombardy for example).[95] By the last half of the ninth century, it was not uncommon for literate people to have direct experience of Horace’s poetry. His influence on the Carolingian Renaissance can be found in the poems of Heiric of Auxerre[nb 24] and in some manuscripts marked with neumes, mysterious notations that may have been an aid to the memorization and discussion of his lyric meters. Ode 4.11 is neumed with the melody of a hymn to John the Baptist, Ut queant laxis, composed in Sapphic stanzas. This hymn later became the basis of the solfege system (Do, re, mi…)—an association with western music quite appropriate for a lyric poet like Horace, though the language of the hymn is mainly Prudentian.[96]Lyons[97] argues that the melody in question was linked with Horace’s Ode well before Guido d’Arezzo fitted Ut queant laxis to it. However, the melody is unlikely to be a survivor from classical times, although Ovid[98] testifies to Horace’s use of the lyre while performing his Odes.

The German scholar, Ludwig Traube, once dubbed the tenth and eleventh centuries The age of Horace (aetas Horatiana), and placed it between the aetas Vergiliana of the eighth and ninth centuries, and the aetas Ovidiana of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, a distinction supposed to reflect the dominant classical Latin influences of those times. Such a distinction is over-schematized since Horace was a substantial influence in the ninth century as well. Traube had focused too much on Horace’s Satires.[99] Almost all of Horace’s work found favor in the Medieval period. In fact medieval scholars were also guilty of over-schematism, associating Horace’s different genres with the different ages of man. A twelfth century scholar encapsulated the theory: “…Horace wrote four different kinds of poems on account of the four ages, the Odes for boys, the Ars Poetica for young men, the Satires for mature men, the Epistles for old and complete men.”[100] It was even thought that Horace had composed his works in the order in which they had been placed by ancient scholars.[nb 25] Despite its naivety, the schematism involved an appreciation of Horace’s works as a collection, the Ars Poetica, Satires and Epistles appearing to find favour as well as the Odes. The later Middle Ages however gave special significance to Satires and Epistles, being considered Horace’s mature works. Dante referred to Horace as Orazio satiro, and he awarded him a privileged position in the first circle of Hell, with Homer, Ovid and Lucan.[101]

Horace’s popularity is revealed in the large number of quotes from all his works found in almost every genre of medieval literature, and also in the number of poets imitating him in quantitative Latin meter . The most prolific imitator of his Odes was the Bavarian monk, Metellus of Tegernsee, who dedicated his work to the patron saint of Tegernsee Abbey, St Quirinus, around the year 1170. He imitated all Horace’s lyrical meters then followed these up with imitations of other meters used by Prudentius and Boethius, indicating that variety, as first modelled by Horace, was considered a fundamental aspect of the lyric genre. The content of his poems however was restricted to simple piety.[102] Among the most successful imitators of Satires and Epistleswas another Germanic author, calling himself Sextus Amarcius, around 1100, who composed four books, the first two exemplifying vices, the second pair mainly virtues.[103]

Petrarch is a key figure in the imitation of Horace in accentual meters. His verse letters in Latin were modelled on the Epistles and he wrote a letter to Horace in the form of an ode. However he also borrowed from Horace when composing his Italian sonnets. One modern scholar has speculated that authors who imitated Horace in accentual rhythms (including stressed Latin and vernacular languages) may have considered their work a natural sequel to Horace’s metrical variety.[104]In France, Horace and Pindar were the poetic models for a group of vernacular authors called the Pléiade, including for example Pierre de Ronsard and Joachim du Bellay. Montaigne made constant and inventive use of Horatian quotes.[105] The vernacular languages were dominant in Spain and Portugal in the sixteenth century, where Horace’s influence is notable in the works of such authors as Garcilaso de la Vega, Juan Boscán Sá de Miranda, Antonio Ferreira and Fray Luis de León, the latter for example writing odes on the Horatian theme beatus ille (happy the man).[106] The sixteenth century in western Europe was also an age of translations (except in Germany, where Horace wasn’t translated until well into the seventeenth century). The first English translator was Thomas Drant, who placed translations of Jeremiah and Horace side by side in Medicinable Morall, 1566. That was also the year that the Scot George Buchananparaphrased the Psalms in a Horatian setting. Ben Jonson put Horace on the stage in 1601 in Poetaster, along with other classical Latin authors, giving them all their own verses to speak in translation. Horace’s part evinces the independent spirit, moral earnestness and critical insight that many readers look for in his poems.[107]

Age of Enlightenment

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, or the Age of Enlightenment, neo-classical culture was pervasive. English literature in the middle of that period has been dubbed Augustan. It is not always easy to distinguish Horace’s influence during those centuries (the mixing of influences is shown for example in one poet’s pseudonym, Horace Juvenal).[nb 26] However a measure of his influence can be found in the diversity of the people interested in his works, both among readers and authors.[108]

New editions of his works were published almost yearly. There were three new editions in 1612 (two in Leiden, one in Frankfurt) and again in 1699 (Utrecht, Barcelona, Cambridge). Cheap editions were plentiful and fine editions were also produced, including one whose entire text was engraved by John Pine in copperplate. The poet James Thomson owned five editions of Horace’s work and the physician James Douglas had five hundred books with Horace-related titles. Horace was often commended in periodicals such as The Spectator, as a hallmark of good judgement, moderation and manliness, a focus for moralising.[nb 27] His verses offered a fund of mottoes, such as simplex munditiis, (elegance in simplicity) splendide mendax (nobly untruthful.), sapere aude, nunc est bibendum, carpe diem (the latter perhaps being the only one still in common use today),[94] quoted even in works as prosaic as Edmund Quincy‘s A treatise of hemp-husbandry(1765). The fictional hero Tom Jones recited his verses with feeling.[109] His works were also used to justify commonplace themes, such as patriotic obedience, as in James Parry’s English lines from an Oxford University collection in 1736:[110]

What friendly Muse will teach my Lays

To emulate the Roman fire?

Justly to sound a Caeser’s praise

Demands a bold Horatian lyre.

Horatian-style lyrics were increasingly typical of Oxford and Cambridge verse collections for this period, most of them in Latin but some like the previous ode in English. John Milton‘s Lycidas first appeared in such a collection. It has few Horatian echoes[nb 28] yet Milton’s associations with Horace were lifelong. He composed a controversial version of Odes 1.5, and Paradise Lost includes references to Horace’s ‘Roman’ Odes 3.1–6 (Book 7 for example begins with echoes of Odes 3.4).[111] Yet Horace’s lyrics could offer inspiration to libertines as well as moralists, and neo-Latin sometimes served as a kind of discrete veil for the risqué. Thus for example Benjamin Loveling authored a catalogue of Drury Lane and Covent Garden prostitutes, in Sapphic stanzas, and an encomium for a dying lady “of salacious memory”.[112] Some Latin imitations of Horace were politically subversive, such as a marriage ode by Anthony Alsop that included a rallying cry for the Jacobite cause. On the other hand, Andrew Marvell took inspiration from Horace’s Odes 1.37 to compose his English masterpiece Horatian Ode upon Cromwell’s Return from Ireland, in which subtly nuanced reflections on the execution of Charles I echo Horace’s ambiguous response to the death of Cleopatra (Marvell’s ode was suppressed in spite of its subtlety and only began to be widely published in 1776). Samuel Johnson took particular pleasure in reading The Odes.[nb 29] Alexander Pope wrote direct Imitations of Horace (published with the original Latin alongside) and also echoed him in Essays and The Rape of the Lock. He even emerged as “a quite Horatian Homer” in his translation of the Iliad.[113]Horace appealed also to female poets, such as Anna Seward (Original sonnets on various subjects, and odes paraphrased from Horace, 1799) and Elizabeth Tollet, who composed a Latin ode in Sapphic meter to celebrate her brother’s return from overseas, with tea and coffee substituted for the wine of Horace’s sympotic settings:

Quos procax nobis numeros, jocosque

Musa dictaret? mihi dum tibique

Temperent baccis Arabes, vel herbis

Pocula Seres[114]

|

What verses and jokes might the bold

Muse dictate? while for you and me

Arabs flavour our cups with beans

Or Chinese with leaves.[115]

|

Horace’s Ars Poetica is second only to Aristotle’s Poetics in its influence on literary theory and criticism. Milton recommended both works in his treatise of Education.[116] Horace’s Satires and Epistleshowever also had a huge impact, influencing theorists and critics such as John Dryden.[117] There was considerable debate over the value of different lyrical forms for contemporary poets, as represented on one hand by the kind of four-line stanzas made familiar by Horace’s Sapphic and Alcaic Odes and, on the other, the loosely structured Pindarics associated with the odes of Pindar. Translations occasionally involved scholars in the dilemmas of censorship. Thus Christopher Smart entirely omitted Odes 4.10 and re-numbered the remaining odes. He also removed the ending of Odes 4.1. Thomas Creechprinted Epodes 8 and 12 in the original Latin but left out their English translations. Philip Francis left out both the English and Latin for those same two epodes, a gap in the numbering the only indication that something was amiss. French editions of Horace were influential in England and these too were regularly bowdlerized.

Most European nations had their own ‘Horaces’: thus for example Friedrich von Hagedorn was called The German Horace and Maciej Kazimierz Sarbiewski The Polish Horace (the latter was much imitated by English poets such as Henry Vaughan and Abraham Cowley). Pope Urban VIII wrote voluminously in Horatian meters, including an ode on gout.[118]

19th century on

Horace maintained a central role in the education of English-speaking elites right up until the 1960s.[119] A pedantic emphasis on the formal aspects of language-learning at the expense of literary appreciation may have made him unpopular in some quarters[120] yet it also confirmed his influence—a tension in his reception that underlies Byron‘s famous lines from Childe Harold (Canto iv, 77):[121]

Then farewell, Horace, whom I hated so

Not for thy faults, but mine; it is a curse

To understand, not feel thy lyric flow,

To comprehend, but never love thy verse.

William Wordsworth‘s mature poetry, including the preface to Lyrical Ballads, reveals Horace’s influence in its rejection of false ornament[122] and he once expressed “a wish / to meet the shade of Horace…”.[nb 30] John Keats echoed the opening of Horace’s Epodes14 in the opening lines of Ode to a Nightingale.[nb 31]

The Roman poet was presented in the nineteenth century as an honorary English gentleman. William Thackeray produced a version of Odes 1.38 in which Horace’s questionable ‘boy’ became ‘Lucy’, and Gerard Manley Hopkins translated the boy innocently as ‘child’. Horace was translated by Sir Theodore Martin (biographer of Prince Albert) but minus some ungentlemanly verses, such as the erotic Odes 1.25 and Epodes 8 and 12. Lord Lytton produced a popular translation and William Gladstone also wrote translations during his last days as Prime Minister.[123]

Edward FitzGerald‘s Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, though formally derived from the Persian ruba’i, nevertheless shows a strong Horatian influence, since, as one modern scholar has observed,”…the quatrains inevitably recall the stanzas of the ‘Odes’, as does the narrating first person of the world-weary, ageing Epicurean Omar himself, mixing sympotic exhortation and ‘carpe diem’ with splendid moralising and ‘memento mori’ nihilism.“[nb 32] Matthew Arnold advised a friend in verse not to worry about politics, an echo of Odes 2.11, yet later became a critic of Horace’s inadequacies relative to Greek poets, as role models of Victorian virtues, observing: “If human life were complete without faith, without enthusiasm, without energy, Horace…would be the perfect interpreter of human life.“[124] Christina Rossetti composed a sonnet depicting a woman willing her own death steadily, drawing on Horace’s depiction of ‘Glycera’ in Odes 1.19.5–6and Cleopatra in Odes 1.37.[nb 33] A. E. Housman considered Odes4.7, in Archilochian couplets, the most beautiful poem of antiquity[125]and yet he generally shared Horace’s penchant for quatrains, being readily adapted to his own elegiac and melancholy strain.[126] The most famous poem of Ernest Dowson took its title and its heroine’s name from a line of Odes 4.1, Non sum qualis eram bonae sub regno Cynarae, as well as its motif of nostalgia for a former flame. Kiplingwrote a famous parody of the Odes, satirising their stylistic idiosyncrasies and especially the extraordinary syntax, but he also used Horace’s Roman patriotism as a focus for British imperialism, as in the story Regulus in the school collection Stalky & Co., which he based on Odes 3.5.[127] Wilfred Owen’s famous poem, quoted above, incorporated Horatian text to question patriotism while ignoring the rules of Latin scansion. However, there were few other echoes of Horace in the war period, possibly because war is not actually a major theme of Horace’s work.[128]

Giacobbe Giusti, Quintus Horatius Flaccus, Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus

Both W.H.Auden and Louis MacNeice began their careers as teachers of classics and both responded as poets to Horace’s influence. Auden for example evoked the fragile world of the 1930s in terms echoing Odes 2.11.1–4, where Horace advises a friend not to let worries about frontier wars interfere with current pleasures.

And, gentle, do not care to know

Where Poland draws her Eastern bow,

What violence is done;

Nor ask what doubtful act allows

Our freedom in this English house,

Our picnics in the sun.[nb 34]

The American poet, Robert Frost, echoed Horace’s Satires in the conversational and sententious idiom of some of his longer poems, such as The Lesson for Today (1941), and also in his gentle advocacy of life on the farm, as in Hyla Brook (1916), evoking Horace’s fons Bandusiae in Ode 3.13. Now at the start of the third millennium, poets are still absorbing and re-configuring the Horatian influence, sometimes in translation (such as a 2002 English/American edition of the Odes by thirty-six poets)[nb 35] and sometimes as inspiration for their own work (such as a 2003 collection of odes by a New Zealand poet).[nb 36]

Horace’s Epodes have largely been ignored in the modern era, excepting those with political associations of historical significance. The obscene qualities of some of the poems have repulsed even scholars[nb 37] yet more recently a better understanding of the nature of Iambic poetry has led to a re-evaluation of the wholecollection.[129][130] A re-appraisal of the Epodes also appears in creative adaptations by recent poets (such as a 2004 collection of poems that relocates the ancient context to a 1950s industrial town).[nb 38]

Translations

- John Dryden successfully adapted three of the Odes (and one Epode) into verse for readers of his own age. Samuel Johnsonfavored the versions of Philip Francis. Others favor unrhymed translations.

- In 1964 James Michie published a translation of the Odes—many of them fully rhymed—including a dozen of the poems in the original Sapphic and Alcaic metres.

- More recent verse translations of the Odes include those by David West (free verse), and Colin Sydenham (rhymed).

- Ars Poetica was first translated into English by Ben Jonson and later by Lord Byron.

- Horace’s Odes and the Mystery of Do-Re-Mi Stuart Lyons (rhymed) Aris & Phillips ISBN 978-0-85668-790-7

Notes

- ^ Quintilian 10.1.96. The only other lyrical poet Quintilian thought comparable with Horace was the now obscure poet/metrical theorist, Caesius Bassus (R. Tarrant, Ancient Receptions of Horace, 280)

- ^ Translated from Persius’ own ‘Satires’ 1.116–17: “omne vafer vitium ridenti Flaccus amico / tangit et admissus circum praecordia ludit.”

- ^ Quoted by N. Rudd from John Dryden’s Discourse Concerning the Original and Progress of Satire, excerpted from W.P.Ker’s edition of Dryden’s essays, Oxford 1926, vol. 2, pp. 86–7

- ^ The year is given in Odes 3.21.1 (“Consule Manlio”), the month in Epistles 1.20.27, the day in Suetonius’ biography Vita (R. Nisbet, Horace: life and chronology, 7)

- ^ “No son ever set a finer monument to his father than Horace did in the sixth satire of Book I…Horace’s description of his father is warm-hearted but free from sentimentality or exaggeration. We see before us one of the common people, a hard-working, open-minded, and thoroughly honest man of simple habits and strict convictions, representing some of the best qualities that at the end of the Republic could still be found in the unsophisticated society of the Italian municipia“—E. Fraenkel, Horace, 5–6

- ^ Odes 3.4.28: “nec (me extinxit) Sicula Palinurus unda”; “nor did Palinurus extinguish me with Sicilian waters”. Maecenas’ involvement is recorded by Appian Bell. Civ. 5.99 but Horace’s ode is the only historical reference to his own presence there, depending however on interpretation. (R. Nisbet, Horace: life and chronology, 10)

- ^ The point is much disputed among scholars and hinges on how the text is interpreted. Epodes 9 for example may offer proof of Horace’s presence if ‘ad hunc frementis’ (‘gnashing at this’ man i.e. the traitrous Roman ) is a misreading of ‘at huc…verterent’ (but hither…they fled) in lines describing the defection of the Galatian cavalry, “ad hunc frementis verterunt bis mille equos / Galli canentes Caesarem” (R. Nisbet, Horace: life and chronology, 12).

- ^ Suetonius signals that the report is based on rumours by employing the terms “traditur…dicitur” / “it is reported…it is said” (E. Fraenkel, Horace, 21)

- ^ According to a recent theory, the three books of Odes were issued separately, possibly in 26, 24 and 23 BC (see G. Hutchinson (2002), Classical Quarterly 52: 517–37)

- ^ 19 BC is the usual estimate but c. 11 BC has good support too (see R. Nisbet, Horace: life and chronology, 18–20

- ^ The date however is subject to much controversy with 22–18 BC another option (see for example R. Syme, The Augustan Aristocracy, 379–81

- ^ “[Lucilius]…resembles a man whose only concern is to force / something into the framework of six feet, and who gaily produces / two hundred lines before dinner and another two hundred after.” – Satire1.10.59–61 (translated by Niall Rudd, The Satires of Horace and Persius, Penguin Classics 1973, p 69)

- ^ There is one reference to Bion by name in Epistles 2.2.60, and the clearest allusion to him is in Satire 1.6, which parallels Bion fragments 1, 2, 16 Kindstrand

- ^ Epistles 1.17 and 1.18.6–8 are critical of the extreme views of Diogenes and also of social adaptations of Cynic precepts, and yet Epistle 1.2 could be either Cynic or Stoic in its orientation (J. Moles, Philosophy and ethics, p. 177

- ^ Satires 1.1.25–26, 74–5, 1.2.111–12, 1.3.76–7, 97–114, 1.5.44, 101–3, 1.6.128–31, 2.2.14–20, 25, 2.6.93–7

- ^ Wilfred Owen, Dulce et decorum est (1917), echoes a line from Carmina 3.2.13, “it is sweet and honourable to die for one’s country”, cited by Stephen Harrison, The nineteenth and twentieth centuries, 340.

- ^ Propertius published his third book of elegies within a year or two of Horace’s Odes 1–3 and mimicked him, for example, in the opening lines, characterizing himself in terms borrowed from Odes 3.1.13 and 3.30.13–14, as a priest of the Muses and as an adaptor of Greek forms of poetry (R. Tarrant, Ancient receptions of Horace, 227)

- ^ Ovid for example probably borrowed from Horace’s Epistle 1.20 the image of a poetry book as a slave boy eager to leave home, adapting it to the opening poems of Tristia 1 and 3 (R. Tarrant, Ancient receptions of Horace), and Tristia 2 may be understood as a counterpart to Horace’s Epistles 2.1, both being letters addressed to Augustus on literary themes (A. Barchiesi, Speaking Volumes, 79–103)

- ^ The comment is in Persius 1.114–18, yet that same satire has been found to have nearly 80 reminiscences of Horace; see D. Hooley, The Knotted Thong, 29

- ^ The allusion to Venusine comes via Horace’s Sermones 2.1.35, while lamp signifies the lucubrations of a conscientious poet. According to Quintilian (93), however, many people in Flavian Rome preferred Lucilius not only to Horace but to all other Latin poets (R. Tarrant, Ancient receptions of Horace, 279)

- ^ Prudentius sometimes alludesto the Odes in a negative context, as expressions of a secular life he is abandoning. Thus for example male pertinax, employed in Prudentius’s Praefatio to describe a wilful desire for victory, is lifted from Odes 1.9.24, where it describes a girl’s half-hearted resistance to seduction. Elsewhere he borrows dux bone from Odes 4.5.5 and 37, where it refers to Augustus, and applies it to Christ (R. Tarrant, Ancient receptions of Horace, 282

- ^ St Jerome, Epistles 22.29, incorporating a quote from 2 ‘Corinthians6.14: qui consensus Christo et Belial? quid facit cum psalterio Horatius?(cited by K. Friis-Jensen, Horace in the Middle Ages, 292)

- ^ Odes 3.3.1–8 was especially influential in promoting the value of heroic calm in the face of danger, describing a man who could bear even the collapse of the world without fear (si fractus illabatur orbis,/impavidum ferient ruinae). Echoes are found in Seneca’s Agamemnon 593–603, Prudentius’s Peristephanon 4.5–12 and Boethius’s Consolatio 1 metrum 4.(R. Tarrant, Ancient receptions of Horace, 283–85)

- ^ Heiric, like Prudentius, gave Horatian motifs a Christian context. Thus the character Lydia in Odes 3.19.15, who would willingly die for her lover twice, becomes in Heiric’s Life of St Germaine of Auxerre a saint ready to die twice for the Lord’s commandments (R. Tarrant, Ancient receptions of Horace, 287–88)

- ^ According to a medieval French commentary on the Satires: “…first he composed his lyrics, and in them, speaking to the young, as it were, he took as subject-matter love affairs and quarrels, banquets and drinking parties. Next he wrote his Epodes, and in them composed invectives against men of a more advanced and more dishonourable age…He next wrote his book about the Ars Poetica, and in that instructed men of his own profession to write well…Later he added his book of Satires, in which he reproved those who had fallen a prey to various kinds of vices. Finally he finished his oeuvre with the Epistles, and in them, following the method of a good farmer, he sowed the virtues where he had rooted out the vices.” (cited by K. Friis-Jensen, Horace in the Middle Ages, 294–302)

- ^ ‘Horace Juvenal’ was author of Modern manners: a poem, 1793

- ^ see for example Spectator 312, 27 Feb. 1712; 548, 28 Nov. 1712; 618, 10 Nov. 1714

- ^ One echo of Horace may be found in line 69: “Were it not better done as others use,/ To sport with Amaryllis in the shade/Or with the tangles of Neaera’s hair?“, which points to the Neara in Odes 3.14.21 (Douglas Bush, Milton: Poetical Works, 144, note 69)

- ^ Cfr. James Boswell, “The Life of Samuel Johnson” Aetat. 20, 1729 where Boswell remarked of Johnson that Horace’s Odes “were the compositions in which he took most delight.”

- ^ The quote, from Memorials of a Tour of Italy (1837), contains allusions to Odes 3.4 and 3.13 (S. Harrison, The nineteenth and twentieth centuries, 334–35)

- ^ “My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains / my sense…” echoes Epodes 14.1–4 (S. Harrison, The nineteenth and twentieth centuries, 335)

- ^ Comment by S. Harrison, editor and contributor to The Cambridge Companion to Horace (S. Harrison, The nineteenth and twentieth centuries, 337

- ^ Rossetti’s sonnet, A Study (a soul), dated 1854, was not published in her own lifetime. Some lines: She stands as pale as Parian marble stands / Like Cleopatra when she turns at bay… (C. Rossetti, Complete Poems, 758

- ^ Quoted from Auden’s poem Out on the lawn I lie in bed, 1933, and cited by S. Harrison, The nineteenth and twentieth centuries, 340

- ^ Edited by McClatchy, reviewed by S. Harrison, Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2003.03.05

- ^ I. Wedde, The Commonplace Odes, Auckland 2003, (cited by S. Harrison, The nineteenth and twentieth centuries, 345)

- ^ ‘Political’ Epodes are 1, 7, 9, 16; notably obscene Epodes are 8 and 12. E. Fraenkel is among the admirers repulsed by these two poems, for another view of which see for example Dee Lesser Clayman, ‘Horace’s Epodes VIII and XII: More than Clever Obscenity?’, The Classical World Vol. 6, No. 1 (September 1975), pp 55–61 JSTOR 4348329

- ^ M. Almond, The Works 2004, Washington, cited by S. Harrison, The nineteenth and twentieth centuries, 346

Citations

- ^ Jump up to:a b J. Michie, The Odes of Horace, 14

- ^ N. Rudd, The Satires of Horace and Persius, 10

- ^ R. Barrow R., The Romans Pelican Books, 119

- ^ Fraenkel, Eduard. Horace. Oxford: 1957, p. 1.

For the Life of Horace by Suetonius, see: (Vita Horati)

- ^ Brill’s Companion to Horace, edited by Hans-Christian Günther, Brill, 2012, p.7, Google Book

- ^ Satires 1.10.30

- ^ Epistles 2.1.69 ff.

- ^ E. Fraenkel, Horace, 2–3

- ^ Satires 2.1.34

- ^ T. Frank, Catullus and Horace, 133–34

- ^ A. Campbell, Horace: A New Interpretation, 84

- ^ Epistles 1.16.49

- ^ R. Nisbet, Horace: life and chronology, 7

- ^ E. Fraenkel, Horace, 3–4

- ^ Jump up to:a b V. Kiernan, Horace: Poetics and Politics, 24

- ^ Satires 1.6.86

- ^ E. Fraenkel, Horace, 4–5

- ^ Jump up to:a b Satires 1.6

- ^ V. Kiernan, Horace: Poetics and Politics, 25

- ^ Odes 2.7

- ^ E. Fraenkel, Horace, 8–9

- ^ E. Fraenkel, Horace, 9–10

- ^ Satires 1.6.48

- ^ Jump up to:a b R. Nisbet, Horace: life and chronology, 8

- ^ V. Kiernan, Horace, 25

- ^ Odes 2.7.10

- ^ Epistles 2.2.51–2

- ^ V. Kiernan, Horace: Poetics and politics

- ^ E. Fraenkel, Horace, 14–15

- ^ Christopher Brown, in A Companion to the Greek Lyric Poets, D.E.Gerber (ed), Leiden 1997, pages 13–88

- ^ Douglas E. Gerber, Greek Iambic Poetry, Loeb Classical Library (1999), Introduction pages i–iv

- ^ D. Mankin, Horace: Epodes,C.U.P., 8

- ^ D. Mankin, Horace: Epodes, 6

- ^ R. Conway, New Studies of a Great Inheritance, 49–50

- ^ V. Kiernan, Horace: Poetics and Politics, 18–19

- ^ F. Muecke, The Satires, 109–10

- ^ R. Lyne, Augustan Poetry and Society, 599

- ^ J. Griffin, Horace in the Thirties, 6

- ^ Jump up to:a b R. Nisbet, Horace: life and chronology, 10

- ^ D. Mankin, Horace: Epodes, 5

- ^ Satires 1.5

- ^ Odes 3.4.28

- ^ Epodes 1 and 9

- ^ E. Fraenkel, Horace, 15

- ^ Satires 2.7.53

- ^ R. Nisbet, Horace: life and chronology, 11

- ^ V. Kiernan, Horace: Poetics and Politics, 61–2

- ^ R. Nisbet, Horace: life and chronology, 13

- ^ Epistles 1.19.35–44

- ^ Epistles 1.1.10

- ^ V. Kiernan, Horace: Poetics and Politics, 149, 153

- ^ Epistles 1.7

- ^ Epistles 1.20.24–5

- ^ R. Nisbet, Horace: life and chronology, 14–15

- ^ E. Fraenkel, Horace, 17–18

- ^ Epistles 2.2

- ^ R. Ferri, The Epistles, 121

- ^ Odes 4.4 and 4.14

- ^ E. Fraenkel, Horace, 23

- ^ R Nisbet, Horace: life and chronology, 17–21

- ^ S. Harrison, Style and poetic texture, 262

- ^ E. Fraenkel, Horace, 124–5

- ^ Gundolf, Friedrich (1916). Goethe. Berlin, Germany: Bondi.

- ^ E. Fraenkel, Horace, 106–7

- ^ E. Fraenkel, Horace, 74

- ^ E. Fraenkel, Horace, 95–6

- ^ J. Griffin, Gods and Religion, 182

- ^ S. Harrison, Lyric and Iambic, 192

- ^ S. Harrison, Lyric and Iambic, 194–6

- ^ Jump up to:a b E. Fraenkel, Horace, 32, 80

- ^ L. Morgan, Satire, 177–8

- ^ S. Harrison, Style and poetic texture, 271

- ^ R. Ferri, The Epistles, p.121-22

- ^ E. Fraenkel, Horace, p. 309

- ^ V. Kiernan, Horace: Poetics and Politics, 28

- ^ J. Moles, Philosophy and ethics, p. 165-69, 177

- ^ K. J. Reckford, Some studies in Horace’s odes on love

- ^ J. Moles, Philosophy and ethics, p. 168

- ^ Santirocco “Unity and Design”, Lowrie “Horace’s Narrative Odes”

- ^ Ancona, “Time and the Erotic”

- ^ J. Moles, Philosophy and ethics, p. 171-73

- ^ Davis “Polyhymnia” and Lowrie “Horace’s Narrative Odes”

- ^ J. Moles, Philosophy and ethics, p. 179

- ^ J. Moles, Philosophy and ethics, p. 174-80

- ^ R. Tarrant, Ancient receptions of Horace, 279

- ^ V. Kiernan, Horace: Poetics and Politics, 176

- ^ D. Money, The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, 326, 332

- ^ R. Lyme, Augustan Poetry and Society, 603

- ^ Niall Rudd, The Satires of Horace and Persius, 14

- ^ R. Tarrant, Ancient receptions of Horace, 282–3

- ^ R. Tarrant, Ancient receptions of Horace, 280

- ^ R. Tarrant, Ancient receptions of Horace, 278

- ^ R. Tarrant, Ancient receptions of Horace, 280–81

- ^ Jump up to:a b R. Tarrant, Ancient receptions of Horace, 283

- ^ R. Tarrant, Ancient receptions of Horace, 285–87

- ^ R. Tarrant, Ancient receptions of Horace, 288–89

- ^ Stuart Lyons, Horace’s Odes and the Mystery of Do-Re-Mi

- ^ Tristia, 4.10.49–50

- ^ B. Bischoff, Living with the satirists, 83–95

- ^ K. Friis-Jensen,Horace in the Middle Ages, 291

- ^ K. Friis-Jensen, Horace in the Middle Ages, 293, 304

- ^ K. Friis-Jensen, Horace in the Middle Ages, 296–8

- ^ K. Friis-Jensen, Horace in the Middle Ages, 302

- ^ K. Friis-Jensen, Horace in the Middle Ages, 299

- ^ Michael McGann, Horace in the Renaissance, 306

- ^ E. Rivers, Fray Luis de León: The Original Poems

- ^ M. McGann, Horace in the Renaissance, 306–7, 313–16

- ^ D. Money, The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, 318, 331, 332

- ^ D. Money, The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, 322

- ^ D. Money, The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, 326–7

- ^ J. Talbot, A Horatian Pun in Paradise Lost, 21–3

- ^ B. Loveling, Latin and English Poems, 49–52, 79–83

- ^ D. Money, The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, 329–31

- ^ E. Tollet, Poems on Several Occasions, 84

- ^ Translation adapted from D. Money, The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, 329

- ^ A. Gilbert, Literary Criticism: Plato to Dryden, 124, 669

- ^ W. Kupersmith, Roman Satirists in Seventeenth Century England, 97–101

- ^ D. Money, The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, 319–25

- ^ S. Harrison, The nineteenth and twentieth centuries, 340

- ^ V. Kiernan, Horace: Poetics and Politics, x

- ^ S. Harrison, The nineteenth and twentieth centuries, 334

- ^ D. Money, The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, 323

- ^ S. Harrison, The nineteenth and twentieth centuries, 335–37

- ^ M. Arnold, Selected Prose, 74

- ^ W. Flesch, Companion to British Poetry, 19th Century, 98

- ^ S. Harrison, The nineteenth and twentieth centuries, 339

- ^ S. Medcalfe, Kipling’s Horace, 217–39

- ^ S. Harrison, the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, 340

- ^ D. Mankin, Horace: Epodes, 6–9

- ^ R. McNeill, Horace, 12

References

- Arnold, Matthew (1970). Selected Prose. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-043058-5.

- Barrow, R (1949). The Romans. Penguin/Pelican Books.

- Barchiesi, A (2001). Speaking Volumes: Narrative and Intertext in Ovid and Other Latin Poets. Duckworth.

- Bischoff, B (1971). “Living with the satirists”. Classical Influences on European Culture AD 500–1500. Cambridge University Press.

- Bush, Douglas (1966). Milton: Poetical Works. Oxford University Press.

- Campbell, A (1924). Horace: A New Interpretation. London.

- Conway, R (1921). New Studies of a Great Inheritance. London.

- Davis, Gregson (1991). Polyhymnia. The Rhetoric to Horatian Lyric Discourse. University of California.

- Ferri, Rolando (2007). “The Epistles”. The Cambridge Companion to Horace. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53684-4.

- Flesch, William (2009). The Facts on File Companion to British Poetry, 19th Century. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8160-5896-9.

- Frank, Tenney (1928). Catullus and Horace. New York.

- Fraenkel, Eduard (1957). Horace. Oxford University Press.

- Friis-Jensen, Karsten (2007). “Horace in the Middle Ages”. The Cambridge Companion to Horace. Cambridge University Press.

- Griffin, Jasper (1993). “Horace in the Thirties”. Horace 2000. Ann Arbor.

- Griffin, Jasper (2007). “Gods and religion”. The Cambridge Companion to Horace. Cambridge university Press.

- Harrison, Stephen (2005). “Lyric and Iambic”. A Companion to Latin Literature. Blackwell Publishing.

- Harrison, Stephen (2007). “Introduction”. The Cambridge Companion to Horace. Cambridge University Press.

- Harrison, Stephen (2007). “Style and poetic texture”. The Cambridge Companion to Horace. Cambridge University Press.

- Harrison, Stephen (2007). “The nineteenth and twentieth centuries”. The Cambridge Companion to Horace. Cambridge University Press.

- Hooley, D (1997). The Knotted Thong: Structures of Mimesis in Persius. Ann Arbor.

- Hutchinson, G (2002). “The publication and individuality of Horace’s Odes 1–3”. Classical Quarterly 52.

- Kiernan, Victor (1999). Horace: Poetics and Politics. St Martin’s Press.

- Kupersmith, W (1985). Roman Satirists in Seventeenth Century England. Lincoln, Nabraska and London.

- Loveling, Benjamin (1741). Latin and English Poems, by a Gentleman of Trinity College, Oxford. London.

- Lowrie, Michèle (1997). Horace’s Narrative Odes. Oxford University Press.

- Lyne, R (1986). “Augustan Poetry and Society”. The Oxford History of the Classical World. Oxford University Press.

- Mankin, David (1995). Horace: Epodes. Cambridge university Press.

- McNeill, Randall (2010). Horace. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-980511-2.

- Michie, James (1967). “Horace the Man”. The Odes of Horace. Penguin Classics.

- Moles, John (2007). “Philosophy and ethics”. The Cambridge Companion to Horace. Cambridge University Press.

- Money, David (2007). “The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries”. The Cambridge Companion to Horace. Cambridge University Press.

- Morgan, Llewelyn (2005). “Satire”. A Companion to Latin Literature. Blackwell Publishing.

- Muecke, Frances (2007). “the Satires”. The Cambridge Companion to Horace. Cambridge University Press.

- Nisbet, Robin (2007). “Horace: life and chronology”. The Cambridge Companion to Horace. Cambridge University Press.

- Reckford, K. J. (1997). Horatius: the man and the hour. 118. American Journal of Philology. pp. 538–612.

- Rivers, Elias (1983). Fray Luis de León: The Original Poems. Grant and Cutler.

- Rossetti, Christina (2001). The Complete Poems. Penguin Books.

- Rudd, Niall (1973). The Satires of Horace and Persius. Penguin Classics.

- Santirocco, Matthew (1986). Unity and Design in Horace’s Odes. University of North Carolina.

- Syme, R (1986). The Augustan Aristocracy. Oxford University Press.

- Talbot, J (2001). “A Horatian Pun in Paradise Lost”. Notes and Queries 48 (1). Oxford University Press.

- Tarrant, Richard (2007). “Ancient receptions of Horace”. The Cambridge Companion to Horace. Cambridge University Press.

- Tollet, Elizabeth (1755). Poems on Several Occasions. London.

Further reading

- Davis, Gregson (1991). Polyhymnia the Rhetoric of Horatian Lyric Discourse. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-91030-3.

- Fraenkel, Eduard (1957). Horace. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Horace (1983). The Complete Works of Horace. Charles E. Passage, trans. New York: Ungar. ISBN 0-8044-2404-7.

- Johnson, W. R. (1993). Horace and the Dialectic of Freedom: Readings in Epistles 1. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-2868-8.

- Lyne, R.O.A.M. (1995). Horace: Behind the Public Poetry. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press. ISBN 0-300-06322-9.

- Lyons, Stuart (1997). Horace’s Odes and the Mystery of Do-Re-Mi. Aris & Phillips.

- Lyons, Stuart (2010). Music in the Odes of Horace. Aris & Phillips.

- Michie, James (1964). The Odes of Horace. Rupert Hart-Davis.

- Newman, J.K. (1967). Augustus and the New Poetry. Brussels: Latomus, revue d’études latines.

- Noyes, Alfred (1947). Horace: A Portrait. New York: Sheed and Ward.

- Perret, Jacques (1964). Horace. Bertha Humez, trans. New York: New York University Press.

- Putnam, Michael C.J. (1986). Artifices of Eternity: Horace’s Fourth Book of Odes. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-1852-6.

- Reckford, Kenneth J. (1969). Horace. New York: Twayne.

- Rudd, Niall, ed. (1993). Horace 2000: A Celebration – Essays for the Bimillennium. Ann Arbor: Univ. of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-10490-X.

- Sydenham, Colin (2005). Horace: The Odes. Duckworth.

- West, David (1997). Horace The Complete Odes and Epodes. Oxford University Press.

- Wilkinson, L.P. (1951). Horace and His Lyric Poetry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.