Giacobbe Giusti, Roman army

Roman soldiers: cornicen — players of the cornu (horn). From the cast of Trajan’s column in the Victoria and Albert museum, London.

Giacobbe Giusti, Roman army

Giacobbe Giusti, Roman army

Poussin Rape SabineLouvre

Giacobbe Giusti, Roman army

Giacobbe Giusti, Roman army

Giacobbe Giusti, Roman army

Relief scene of Roman legionaries marching, from the Column of Marcus Aurelius, Rome, Italy, 2nd century AD.

Giacobbe Giusti, Roman army

Giacobbe Giusti, Roman army

Giacobbe Giusti, Roman army

Giacobbe Giusti, Roman army

Giacobbe Giusti, Roman army

Giacobbe Giusti, Roman army

Warrior weapons found in a tomb in Lanuvium, near Rome. Vth century BC. Kept in Diocletian’s Baths Museum, Rome

Giacobbe Giusti, Roman army

Battaglia tra Romani e barbari all’epoca delle guerre marcomanniche

(sarcofago di Portonaccio, Roma, Museo Nazionale Romano–palazzo Massimo alle Terme).

Giacobbe Giusti, Roman army

Rome-Capitole-StatueConstantin-nobg.png

Giacobbe Giusti, Roman army

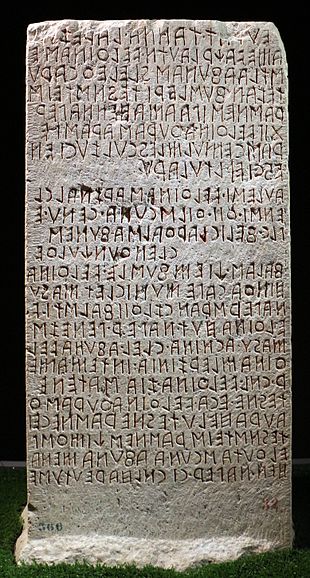

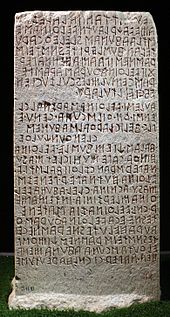

Stèle trouvée sur le Forum Romain, à proximité du Lacus Curtius, représentant un cavalier romain du ive siècle av. J.-C.

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Military of ancient Rome |

|---|

| Military of Ancient Rome portal |

The Roman army(Latin: exercitus Romanus) was the terrestrial armed forces deployed by the Romans throughout the duration of Ancient Rome, from the Roman Kingdom (to c. 500 BC) to the Roman Republic (500–31 BC) and the Roman Empire(31 BC – 395), and its medieval continuation the Eastern Roman Empire. It is thus a term that may span approximately 2,206 years (753 BC to 1453 AD), during which the Roman armed forces underwent numerous permutations in composition, organisation, equipment and tactics, while conserving a core of lasting traditions.[1][2][3].

Historical overview

Early Roman army (c. 500 BC to c. 300 BC)

The Early Roman army was the armed force of the Roman Kingdomand of the early Republic (to c. 300 BC). During this period, when warfare chiefly consisted of small-scale plundering raids, it has been suggested that the army followed Etruscan or Greek models of organisation and equipment. The early Roman army was based on an annual levy.

The infantry ranks were filled with the lower classes while the cavalry (equites or celeres) were left to the patricians, because the wealthier could afford horses. Moreover, the commanding authority during the regal period was the high king. Until the establishment of the Republic and the office of consul, the king assumed the role of commander-in-chief.[4] However, from about 508 BC Rome no longer had a king. The commanding position of the army was given to the consuls, “who were charged both singly and jointly to take care to preserve the Republic from danger”.[5]

The term legion is derived from the Latin word legio; which ultimately means draft or levy. At first there were only four legions. These legions were numbered “I” to “IIII”, with the fourth being written as such and not “IV”. The first legion was seen as the most prestigious. The bulk of the army was made up of citizens. These citizens could not choose the legion to which they were allocated. Any man “from ages 16–46 were selected by ballot” and assigned to a legion.[6]

Until the Roman military disaster of 390 BC at the Battle of the Allia, Rome’s army was organised similarly to the Greek phalanx. This was due to Greek influence in Italy “by way of their colonies”. Patricia Southern quotes ancient historians Livy and Dionysius in saying that the “phalanx consisted of 3,000 infantry and 300 cavalry”.[7] Each man had to provide his equipment in battle; the military equipment which he could afford determined which position he took in the battle. Politically they shared the same ranking system in the Comitia Centuriata; which ultimately vis-à-vis placed the men on the battlefield.[clarification needed]

Roman army of the mid-Republic (c. 300–88 BC)

The Roman army of the mid-Republic was also known as the “manipular army” or the “Polybian army” after the Greek historian Polybius, who provides the most detailed extant description of this phase. The Roman army started to have a full-time strength of 150,000 at all times and 3/4 of the rest were levied.

During this period, the Romans, while maintaining the levy system, adopted the Samnite manipular organisation for their legions and also bound all the other peninsular Italian states into a permanent military alliance (see Socii). The latter were required to supply (collectively) roughly the same number of troops to joint forces as the Romans to serve under Roman command. Legions in this phase were always accompanied on campaign by the same number of allied alae (Roman non-citizen auxiliaries), units of roughly the same size as legions.

After the 2nd Punic War (218–201 BC), the Romans acquired an overseas empire, which necessitated standing forces to fight lengthy wars of conquest and to garrison the newly gained provinces. Thus the army’s character mutated from a temporary force based entirely on short-term conscription to a standing army in which the conscripts were supplemented by a large number of volunteers willing to serve for much longer than the legal six-year limit. These volunteers were mainly from the poorest social class, who did not have plots to tend at home and were attracted by the modest military pay and the prospect of a share of war booty. The minimum property requirement for service in the legions, which had been suspended during the 2nd Punic War, was effectively ignored from 201 BC onward in order to recruit sufficient volunteers. Between 150-100 BC, the manipular structure was gradually phased out, and the much larger cohort became the main tactical unit. In addition, from the 2nd Punic War onward, Roman armies were always accompanied by units of non-Italian mercenaries, such as Numidian light cavalry, Cretan archers, and Balearic slingers, who provided specialist functions that Roman armies had previously lacked.

Roman army of the late Republic (88–30 BC)

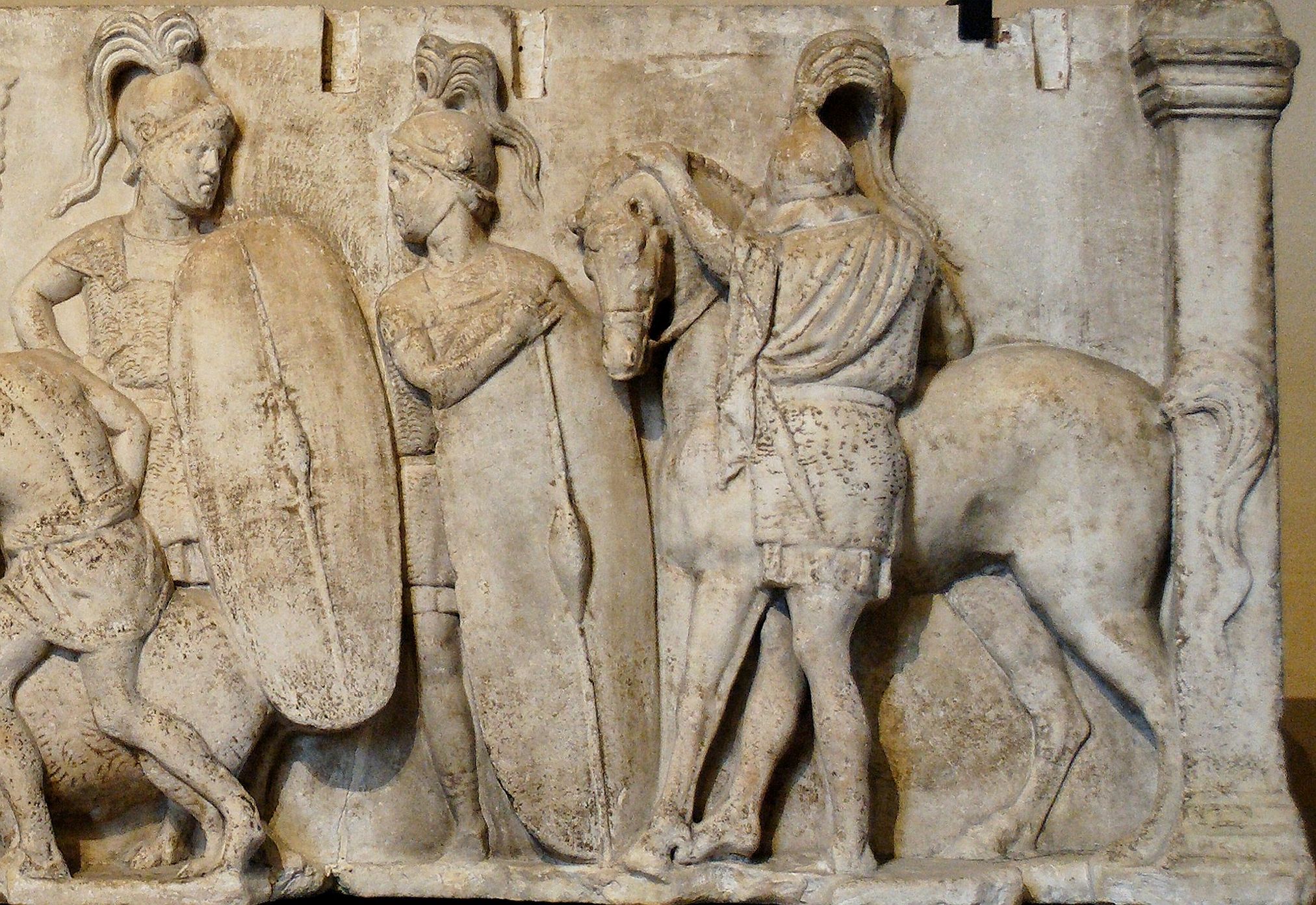

Imperial Roman legionaries in tight formation, a relief from Glanum, a Roman town in what is now southern France that was inhabited from 27 BC to 260 AD (when it was sacked by invading Alemanni)

The Roman army of the late Republic (88–30 BC) marks the continued transition between the conscription-based citizen-levy of the mid-Republic and the mainly volunteer, professional standing forces of the imperial era. The main literary sources for the army’s organisation and tactics in this phase are the works of Julius Caesar, the most notable of a series of warlords who contested for power in this period. As a result of the Social War (91–88 BC), all Italians were granted Roman citizenship, the old allied alae were abolished and their members integrated into the legions. Regular annual conscription remained in force and continued to provide the core of legionary recruitment, but an ever-increasing proportion of recruits were volunteers, who signed up for 16-year terms as opposed to the maximum 6 years for conscripts. The loss of ala cavalry reduced Roman/Italian cavalry by 75%, and legions became dependent on allied native horse for cavalry cover. This period saw the large-scale expansion of native forces employed to complement the legions, made up of numeri (“units”) recruited from tribes within Rome’s overseas empire and neighbouring allied tribes. Large numbers of heavy infantry and cavalry were recruited in Spain, Gaul and Thrace, and archers in Thrace, Anatolia and Syria. However, these native units were not integrated with the legions, but retained their own traditional leadership, organisation, armour and weapons.

Imperial Roman army (30 BC – AD 284)

During this period the Republican system of citizen-conscription was replaced by a standing professional army of mainly volunteers serving standard 20-year terms (plus 5 as reservists), although many in the service of the empire would serve as many as 30 to 40 years on active duty, as established by the first Roman emperor, Augustus (sole ruler 30 BC – AD 14).Regular annual conscription of citizens was abandoned and only decreed in emergencies (e.g. during the Illyrian revolt 6–9 AD). Under Augustus there were 28 legions, consisting almost entirely of heavy infantry, with about 5,000 men each (total 125,000). This had increased to a peak of 33 legions of about 5,500 men each (c. 180,000 men in total) by AD 200 under Septimius Severus. Legions continued to recruit Roman citizens, mainly the inhabitants of Italy and Roman colonies, until 212. Legions were flanked by the auxilia, a corps of regular troops recruited mainly from peregrini, imperial subjects who did not hold Roman citizenship (the great majority of the empire’s inhabitants until 212, when all were granted citizenship). Auxiliaries, who served a minimum term of 25 years, were also mainly volunteers, but regular conscription of peregrini was employed for most of the 1st century AD. The auxiliaconsisted, under Augustus, of about 250 regiments of roughly cohortsize, that is, about 500 men (in total 125,000 men, or 50% of total army effectives). Under Severus the number of regiments increased to about 400, of which about 13% were double-strength (250,000 men, or 60% of total army). Auxilia contained heavy infantry equipped similarly to legionaries, and almost all the army’s cavalry (both armoured and light), and archers and slingers.

Later Roman army (284–476 AD) continuing as East Roman army (476–641 AD)

Stone-carved relief depicting the liberation of a besieged city by a relief force, with those defending the walls making a sortie (i.e. a sudden attack against a besieging enemy from within the besieged town); Western Roman Empire, early 5th Century AD

The Late Roman army period stretches from (284–476 AD and its continuation, in the surviving eastern half of the empire, as the East Roman army to 641). In this phase, crystallised by the reforms of the emperor Diocletian (ruled 284–305 AD), the Roman army returned to regular annual conscription of citizens, while admitting large numbers of non-citizen barbarian volunteers. However, soldiers remained 25-year professionals and did not return to the short-term levies of the Republic. The old dual organisation of legions and auxilia was abandoned, with citizens and non-citizens now serving in the same units. The old legions were broken up into cohort or even smaller sizes. At the same time, a substantial proportion of the army’s effectives were stationed in the interior of the empire, in the form of comitatus praesentales, armies that escorted the emperors.

Middle Byzantine army (641–1081 AD)

The Middle Byzantine army (641–1081 AD) was the army of the Byzantine state in its classical form (i.e. after the permanent loss of its Near Eastern and North African territories to the Arab conquests after 641 AD). This army was largely composed of semi-professional troops (soldier-farmers) based on the themata military provinces, supplemented by a small core of professional regiments known as the tagmata. Ibn al-Fakih estimated the strength of the themata forces in the East c. 902 at 85,000 and Kodama c. 930 at 70,000.[8] This structure pertained when the empire was on the defensive, in the 10th century the empire was increasingly involved in territorial expansion, and the themata troops became progressively more irrelevant, being gradually replaced by ‘provincial tagmata’ units and an increased use of mercenaries.

Komnenian Byzantine army (1081–1204)

The Komnenian Byzantine army was named after the Komnenosdynasty, which ruled from 1081–1185. This was an army built virtually from scratch after the permanent loss of half of Byzantium’s traditional main recruiting ground of Anatolia to the Turks following the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, and the destruction of the last regiments of the old army in the wars against the Normans in the early 1080s. It survived until the fall of Constantinople to the Western crusaders in 1204. This army had a large number of mercenary regiments composed of troops of foreign origin such as the Varangian Guard, and the pronoia system was introduced.

Palaiologan Byzantine army (1261–1453)

The Palaiologan Byzantine army was named after the Palaiologosdynasty (1261–1453), which ruled Byzantium from the recovery of Constantinople from the Crusaders until its fall to the Turks in 1453. Initially, it continued some practices inherited from the Komnenian era and retained a strong native element until the late 13th century. During the last century of its existence, however, the empire was little more than a city-state that hired foreign mercenary bands for its defence. Thus the Byzantine army finally lost any meaningful connection with the standing imperial Roman army.[citation needed]

This article contains the summaries of the detailed linked articles on the historical phases above, Readers seeking discussion of the Roman army by theme, rather than by chronological phase, should consult the following articles:

History

Corps

Strategy and tactics

Equipment & other

Some of the Roman army’s many tactics are still used in modern-day armies today.

Early Roman army (c. 550 to c. 300 BC)

Until c. 550 BC, there was no “national” Roman army, but a series of clan-based war-bands which only coalesced into a united force in periods of serious external threat. Around 550 BC, during the period conventionally known as the rule of king Servius Tullius, it appears that a universal levy of eligible adult male citizens was instituted. This development apparently coincided with the introduction of heavy armour for most of the infantry. Although originally low in numbers the Roman infantry was extremely tactical and developed some of the most influential battle strategies to date.

The early Roman army was based on a compulsory levy from adult male citizens which was held at the start of each campaigning season, in those years that war was declared. There were no standing or professional forces. During the Regal Era (to c. 500 BC), the standard levy was probably of 9,000 men, consisting of 6,000 heavily armed infantry (probably Greek-style hoplites), plus 2,400 light-armed infantry (rorarii, later called velites) and 600 light cavalry (equites celeres). When the kings were replaced by two annually elected praetores in c. 500 BC, the standard levy remained of the same size, but was now divided equally between the Praetors, each commanding one legion of 4,500 men.

It is likely that the hoplite element was deployed in a Greek-style phalanx formation in large set-piece battles. However, these were relatively rare, with most fighting consisting of small-scale border-raids and skirmishing. In these, the Romans would fight in their basic tactical unit, the centuria of 100 men. In addition, separate clan-based forces remained in existence until c. 450 BC at least, although they would operate under the Praetors’ authority, at least nominally.

In 493 BC, shortly after the establishment of the Roman Republic, Rome concluded a perpetual treaty of military alliance (the foedus Cassianum), with the combined other Latin city-states. The treaty, probably motivated by the need for the Latins to deploy a united defence against incursions by neighbouring hill-tribes, provided for each party to provide an equal force for campaigns under unified command. It remained in force until 358 BC.

Roman army of the mid-Republic (c. 300 – 107 BC)

Levy of the army, detail of the carved relief on the Altar of Domitius Ahenobarbus, 122-115 BC.

The central feature of the Roman army of the mid-Republic, or the Polybian army, was the manipular organization of its battle-line. Instead of a single, large mass (the phalanx) as in the Early Roman army, the Romans now drew up in three lines consisting of small units (maniples) of 120 men, arrayed in chessboard fashion, giving much greater tactical strength and flexibility. This structure was probably introduced in c. 300 BC during the Samnite Wars. Also probably dating from this period was the regular accompaniment of each legion by a non-citizen formation of roughly equal size, the ala, recruited from Rome’s Italian allies, or socii. The latter were c. 150 autonomous states which were bound by a treaty of perpetual military alliance with Rome. Their sole obligation was to supply to the Roman army, on demand, a number of fully equipped troops up to a specified maximum each year.

The Second Punic War (218–201 BC) saw the addition of a third element to the existing dual Roman/Italian structure: non-Italian mercenaries with specialist skills lacking in the legions and alae: Numidian light cavalry, Cretan archers, and slingers from the Balearic islands. From this time, these units always accompanied Roman armies.

The Republican army of this period, like its earlier forebear, did not maintain standing or professional military forces, but levied them, by compulsory conscription, as required for each campaigning season and disbanded thereafter (although formations could be kept in being over winter during major wars). The standard levy was doubled during the Samnite Wars to 4 legions (2 per Consul), for a total of c. 18,000 Roman troops and 4 allied alae of similar size. Service in the legions was limited to property-owning Roman citizens, normally those known as iuniores (age 16–46). The army’s senior officers, including its commanders-in-chief, the Roman Consuls, were all elected annually at the People’s Assembly. Only equites (members of the Roman knightly order) were eligible to serve as senior officers. Iuniores of the highest social classes (equites and the First Class of commoners) provided the legion’s cavalry, the other classes the legionary infantry. The proletarii (those assessed at under 400 drachmae wealth) were ineligible for legionary service and were assigned to the fleets as oarsmen. Elders, vagrants, freedmen, slaves and convicts were excluded from the military levy, save in emergencies.

The legionary cavalry also changed, probably around 300 BC onwards from the light, unarmoured horse of the early army to a heavy force with metal armour (bronze cuirasses and, later, chain-mail shirts). Contrary to a long-held view, the cavalry of the mid-Republic was a highly effective force that generally prevailed against strong enemy cavalry forces (both Gallic and Greek) until it was decisively beaten by the Carthaginian general Hannibal‘s horsemen during the second Punic War. This was due to Hannibal’s greater operational flexibility owing to his Numidian light cavalry.

The Polybian army’s operations during its existence can be divided into three broad phases. (1) The struggle for hegemony over Italy, especially against the Samnite League (338–264 BC); (2) the struggle with Carthage for hegemony in the western Mediterranean Sea (264–201 BC); and (3) the struggle against the Hellenistic monarchies for control of the eastern Mediterranean (201–91 BC). During the earlier phase, the normal size of the levy (including allies) was in the region of 40,000 men (2 consular armies of c. 20,000 men each).

During the latter phase, with lengthy wars of conquest followed by permanent military occupation of overseas provinces, the character of the army necessarily changed from a temporary force based entirely on short-term conscription to a standing army in which the conscripts, whose service was in this period limited by law to 6 consecutive years, were complemented by large numbers of volunteers who were willing to serve for much longer periods. Many of the volunteers were drawn from the poorest social class, which until the 2nd Punic War had been excluded from service in the legions by the minimum property requirement: during that war, extreme manpower needs had forced the army to ignore the requirement, and this practice continued thereafter. Maniples were gradually phased out as the main tactical unit, and replaced by the larger cohorts used in the allied alae, a process probably complete by the time the general Marius assumed command in 107 BC. (The “Marian reforms” of the army hypothesised by some scholars are today seen by other scholars as having evolved earlier and more gradually.)

In the period after the defeat of Carthage in 201 BC, the army was campaigning exclusively outside Italy, resulting in its men being away from their home plots of land for many years at a stretch. They were assuaged by the large amounts of booty that they shared after victories in the rich eastern theatre. But in Italy, the ever-increasing concentration of public lands in the hands of big landowners, and the consequent displacement of the soldiers’ families, led to great unrest and demands for land redistribution. This was successfully achieved, but resulted in the disaffection of Rome’s Italian allies, who as non-citizens were excluded from the redistribution. This led to the mass revolt of the socii and the Social War (91-88 BC). The result was the grant of Roman citizenship to all Italians and the end of the Polybian army’s dual structure: the alae were abolished and the socii recruited into the legions.

Imperial Roman army (30 BC – AD 284 )

Recreation of a Roman soldier wearing plate armour (lorica segmentata), National Military Museum, Romania.

Roman relief fragment depicting the Praetorian Guard, c. 50 AD

Relief scene of Roman legionariesmarching, from the Column of Marcus Aurelius, Rome, Italy, 2nd century AD

Under the founder–emperor Augustus (ruled 30 BC – 14 AD), the legions, c. 5,000-strong all-heavy infantry formations recruited from Roman citizens only, were transformed from a mixed conscript and volunteer corps serving an average of 10 years, to all-volunteer units of long-term professionals serving a standard 25-year term (conscription was only decreed in emergencies). In the later 1st century, the size of a legion’s First Cohort was doubled, increasing legionary personnel to c. 5,500.

Alongside the legions, Augustus established the auxilia, a regular corps of similar numbers to the legions, recruited from the peregrini (non-citizen inhabitants of the empire – about 90% of the empire’s population in the 1st century). As well as comprising large numbers of extra heavy infantry equipped in a similar manner to legionaries, the auxilia provided virtually all the army’s cavalry (heavy and light), light infantry, archers and other specialists. The auxilia were organised in c. 500-strong units called cohortes (all-infantry), alae(all-cavalry) and cohortes equitatae (infantry with a cavalry contingent attached). Around 80 AD, a minority of auxiliary regiments were doubled in size. Until about 68 AD, the auxilia were recruited by a mix of conscription and voluntary enlistment. After that time, the auxilia became largely a volunteer corps, with conscription resorted to only in emergencies. Auxiliaries were required to serve a minimum of 25 years, although many served for longer periods. On completion of their minimum term, auxiliaries were awarded Roman citizenship, which carried important legal, fiscal and social advantages. Alongside the regular forces, the army of the Principate employed allied native units (called numeri) from outside the empire on a mercenary basis. These were led by their own aristocrats and equipped in traditional fashion. Numbers fluctuated according to circumstances and are largely unknown.

As all-citizen formations, and symbolic garantors of the dominance of the Italian “master-nation”,[citation needed]legions enjoyed greater social prestige than the auxilia. This was reflected in better pay and benefits. In addition, legionaries were equipped with more expensive and protective armour than auxiliaries. However, in 212, the emperor Caracallagranted Roman citizenship to all the empire’s inhabitants. At this point, the distinction between legions and auxilia became moot, the latter becoming all-citizen units also. The change was reflected in the disappearance, during the 3rd century, of legionaries’ special equipment, and the progressive break-up of legions into cohort-sized units like the auxilia.

By the end of Augustus’ reign, the imperial army numbered some 250,000 men, equally split between legionaries and auxiliaries (25 legions and c. 250 auxiliary regiments). The numbers grew to a peak of about 450,000 by 211 (33 legions and c. 400 auxiliary regiments). By then, auxiliaries outnumbered legionaries substantially. From the peak, numbers probably underwent a steep decline by 270 due to plague and losses during multiple major barbarian invasions. Numbers were restored to their early 2nd-century level of c. 400,000 (but probably not to their 211 peak) under Diocletian (r. 284–305). After the empire’s borders became settled (on the Rhine–Danube line in Europe) by 68, virtually all military units (except the Praetorian Guard) were stationed on or near the borders, in roughly 17 of the 42 provinces of the empire in the reign of Hadrian (r. 117–38).

The military chain of command was relatively uniform across the Empire. In each province, the deployed legions’ legati (legion commanders, who also controlled the auxiliary regiments attached to their legion) reported to the legatus Augusti pro praetore (provincial governor), who also headed the civil administration. The governor in turn reported direct to the emperor in Rome. There was no army general staff in Rome, but the leading praefectus praetorio(commander of the Praetorian Guard) often acted as the emperor’s de facto military chief-of-staff.

Legionary rankers were relatively well-paid, compared to contemporary common labourers. Compared with their subsistence-level peasant families, they enjoyed considerable disposable income, enhanced by periodic cash bonuses on special occasions such as the accession of a new emperor. In addition, on completion of their term of service, they were given a generous discharge bonus equivalent to 13 years’ salary. Auxiliaries were paid much less in the early 1st century, but by 100 AD, the differential had virtually disappeared. Similarly, in the earlier period, auxiliaries appear not to have received cash and discharge bonuses, but probably did so from Hadrian onwards. Junior officers (principales), the equivalent of non-commissioned officers in modern armies, could expect to earn up to twice basic pay. Legionary centurions, the equivalent of mid-level commissioned officers, were organised in an elaborate hierarchy. Usually risen from the ranks, they commanded the legion’s tactical sub-units of centuriae (c. 80 men) and cohorts (c. 480 men). They were paid several multiples of basic pay. The most senior centurion, the primus pilus, was elevated to equestrian rank upon completion of his single-year term of office. The senior officers of the army, the legati legionis (legion commanders), tribuni militum (legion staff officers) and the praefecti (commanders of auxiliary regiments) were all of at least equestrian rank. In the 1st and early 2nd centuries, they were mainly Italian aristocrats performing the military component of their cursus honorum (conventional career-path). Later, provincial career officers became predominant. Senior officers were paid enormous salaries, multiples of at least 50 times basic.

A typical Roman army during this period consisted of five to six legions. One legion was made up of 10 cohorts. The first cohort had five centuria each of 160 soldiers. In the second through tenth cohorts there were six centuria of 80 men each. These do not include archers, cavalry or officers.

Soldiers spent only a fraction of their lives on campaign. Most of their time was spent on routine military duties such as training, patrolling, and maintenance of equipment etc. Soldiers also played an important role outside the military sphere. They performed the function of a provincial governor’s police force. As a large, disciplined and skilled force of fit men, they played a crucial role in the construction of a province’s Roman military and civil infrastructure: in addition to constructing forts and fortified defences such as Hadrian’s Wall, they built roads, bridges, ports, public buildings, entire new cities (Roman colonies), and also engaged in large-scale forest clearance and marsh drainage to expand the province’s available arable land.

Soldiers, mostly drawn from polytheistic societies, enjoyed wide freedom of worship in the polytheistic Roman system. They revered their own native deities, Roman deities and the local deities of the provinces in which they served. Only a few religions were banned by the Roman authorities, as being incompatible with the official Roman religion and/or politically subversive, notably Druidism and Christianity. The later Principate saw the rise in popularity among the military of Eastern mystery cults, generally centred on one deity, and involving secret rituals divulged only to initiates. By far the most popular in the army was Mithraism, an apparently syncretist religion which mainly originated in Asia Minor.

Late Roman army/East Roman army (284–641)

The Late Roman army is the term used to denote the military forces of the Roman Empire from the accession of Emperor Diocletian in 284 until the Empire’s definitive division into Eastern and Western halves in 395. A few decades afterwards, the Western army disintegrated as the Western empire collapsed. The East Roman army, on the other hand, continued intact and essentially unchanged until its reorganization by themes and transformation into the Byzantine army in the 7th century. The term “late Roman army” is often used to include the East Roman army.

The army of the Principate underwent a significant transformation, as a result of the chaotic 3rd century. Unlike the Principate army, the army of the 4th century was heavily dependent on conscription and its soldiers were more poorly remunerated than in the 2nd century. Barbarians from outside the empire probably supplied a much larger proportion of the late army’s recruits than in the army of the 1st and 2nd centuries.

The size of the 4th-century army is controversial. More dated scholars (e.g. A.H.M. Jones, writing in the 1960s) estimated the late army as much larger than the Principate army, half the size again or even as much as twice the size. With the benefit of archaeological discoveries of recent decades, many contemporary historians view the late army as no larger than its predecessor: under Diocletian c. 390,000 (the same as under Hadrian almost two centuries earlier) and under Constantine no greater, and probably somewhat smaller, than the Principate peak of c. 440,000. The main change in structure was the establishment of large armies that accompanied the emperors (comitatus praesentales) and were generally based away from the frontiers. Their primary function was to deter usurpations. The legionswere split up into smaller units comparable in size to the auxiliary regiments of the Principate. In parallel, legionary armour and equipment were abandoned in favour of auxiliary equipment. Infantry adopted the more protective equipment of the Principate cavalry.

The role of cavalry in the late army does not appear to have been enhanced as compared with the army of the Principate. The evidence is that cavalry was much the same proportion of overall army numbers as in the 2nd century and that its tactical role and prestige remained similar. Indeed, the cavalry acquired a reputation for incompetence and cowardice for their role in three major battles in mid-4th century. In contrast, the infantry retained its traditional reputation for excellence.

The 3rd and 4th centuries saw the upgrading of many existing border forts to make them more defensible, as well as the construction of new forts with much higher defensive specifications. The interpretation of this trend has fuelled an ongoing debate whether the army adopted a defence-in-depth strategy or continued the same posture of “forward defence” as in the early Principate. Many elements of the late army’s defence posture were similar to those associated with forward defence, such as a looser forward location of forts, frequent cross-border operations, and external buffer-zones of allied barbarian tribes. Whatever the defence strategy, it was apparently less successful in preventing barbarian incursions than in the 1st and 2nd centuries. This may have been due to heavier barbarian pressure, and/or to the practice of keeping large armies of the best troops in the interior, depriving the border forces of sufficient support.

Byzantine army (641–1081)

Komnenian Byzantine army (1081–1204)

Emperor John II Komnenos, the most successful commander of the Komnenian army.

The Komnenian period marked a rebirth of the Byzantine army. At the beginning of the Komnenian period in 1081, the Byzantine Empire had been reduced to the smallest territorial extent. Surrounded by enemies, and financially ruined by a long period of civil war, the empire’s prospects looked grim.

At the beginning of the Komnenian period, the Byzantine army was reduced to a shadow of its former self: during the 11th century, decades of peace and neglect had reduced the old thematic forces, and the Battle of Manzikert in 1071 had destroyed the professional tagmata, the core of the Byzantine army. At Manzikert and later at Dyrrhachium, units tracing their lineage for centuries back to Late Roman army were wiped out, and the subsequent loss of Asia Minor deprived the Empire of its main recruiting ground. In the Balkans, at the same time, the Empire was exposed to invasions by the Norman Kingdom of Sicily, and by Pecheneg raids across the Danube.

The Byzantine army’s nadir was reached in 1091, when Alexios I could manage to field only 500 soldiers from the Empire’s professional forces. These formed the nucleus of the army, with the addition of the armed retainers of Alexios’ relatives and the nobles enrolled in the army and the substantial aid of a large force of allied Cumans, which won the Battle of Levounion against the Pechenegs (Petcheneks or Patzinaks).[9] Yet, through a combination of skill, determination and years of campaigning, Alexios, John and Manuel Komnenos managed to restore the power of the Byzantine Empire by constructing a new army from scratch. This process should not, however, at least in its earlier phases, be seen as a planned exercise in military restructuring. In particular, Alexios I was often reduced to reacting to events rather than controlling them; the changes he made to the Byzantine army were largely done out of immediate necessity and were pragmatic in nature.

The new force had a core of units which were both professional and disciplined. It contained formidable guards units such as the Varangians, the Athanatoi, a unit of heavy cavalry stationed in Constantinople, the Vardariotai and the Archontopouloi, recruited by Alexios from the sons of dead Byzantine officers, foreign mercenary regiments, and also units of professional soldiers recruited from the provinces. These provincial troops included kataphraktoi cavalry from Macedonia, Thessaly and Thrace, and various other provincial forces such as Trebizond Archers from the Black Sea coast of Anatolia. Alongside troops raised and paid for directly by the state the Komnenian army included the armed followers of members of the wider imperial family and its extensive connections. In this can be seen the beginnings of the feudalisation of the Byzantine military. The granting of pronoia holdings, where land, or more accurately rights to revenue from land, was held in return for military obligations, was beginning to become a notable element in the military infrastructure towards the end of the Komnenian period, though it became much more important subsequently.

In 1097, the Byzantine army numbered around 70,000 men altogether.[10] By 1180 and the death of Manuel Komnenos, whose frequent campaigns had been on a grand scale, the army was probably considerably larger. During the reign of Alexios I, the field army numbered around 20,000 men which was increased to about 30,000 men in John II’s reign.[11] By the end of Manuel I’s reign the Byzantine field army had risen to 40,000 men.

Palaiologan Byzantine army (1261–1453)

The Palaiologan army refers to the military forces of the Byzantine Empire from the late 13th century to its final collapse in the mid 15th century, under the House of the Palaiologoi. The army was a direct continuation of the forces of the Nicaean army, which itself was a fractured component of the formidable Komnenian army. Under the first Palaiologan emperor, Michael VIII, the army’s role took an increasingly offensive role whilst the naval forces of the Empire, weakened since the days of Andronikos I Komnenos, were boosted to include thousands of skilled sailors and some 80 ships. Due to the lack of land to support the army, the Empire required the use of large numbers of mercenaries.

After Andronikos II took to the throne, the army fell apart and the Byzantines suffered regular defeats at the hands of their eastern opponents, although they would continue to enjoy success against the crusader territories in Greece. By c. 1350, following a destructive civil war and the outbreak of the Black Death, the Empire was no longer capable of raising troops and the supplies to maintain them. The Empire came to rely upon troops provided by Serbs, Bulgarians, Venetians, Latins, Genoans and Ottoman Turks to fight the civil wars that lasted for the greater part of the 14th century, with the latter foe being the most successful in establishing a foothold in Thrace. The Ottomans swiftly expanded through the Balkans and cut off Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, from the surrounding land. The last decisive battle was fought by the Palaiologan army in 1453, when Constantinople was besieged and fellon 29 May. The last isolated remnants of the Byzantine state were conquered by 1461.

- Military of ancient Rome

- Roman legion

- Roman auxiliaries

- Equestrian order

- List of Roman legions

- List of Roman auxiliary regiments

- Late Roman army

- Byzantine army

- East Roman army

References

- ^ The Complete Roman Army, Adrian Goldsworthy Thames & Hudson, 2011

- ^ The Roman Army: A Social and Institutional History, Pat Southern, Oxford University Press, 2007

- ^ Companion to the Roman Army, Paul Erdkamp, John Wiley & Sons, 31 Mar 2011

- ^ Rostovtzeff, Michael. Rome. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1960

- ^ Vegetius, The Military Institutions of the Romans (J. Clark, transl.) Harrisburg Penn.; 1944.

- ^ Dando-Collins, Stephen. Legions of Rome. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2010.

- ^ Southern, Pat. The Roman Army: A Social and Institutional History. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- ^ Heath, Ian (1979). Byzantine armies, 886-1118. Osprey. p. 19. ISBN 978-0850453065.

- ^ Angold, p. 127

- ^ Konstam, p. 141.

- ^ W. Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society, 680

- Legions and Legionaries in the Age of Augustus

- The Roman Centurion

- Roman Warriors: The Myth of the Military Machine

- Roman Cavalry

- Protecting the Emperor: The Praetorian Guard

- Diocletian and the Roman Army

- The Last Legion

- Life of Roman legionary

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_army