Giacobbe Giusti, Odysseus (/oʊˈdɪsiəs, oʊˈdɪsjuːs/; Greek: Ὀδυσσεύς, Ὀδυσεύς, Ὀdysseús [odysse͜ús]), also known by the Latin variant Ulysses)

Odysseus and the Sirens, Ulixes mosaic at the Bardo National Museum in Tunis, Tunisia, 2nd century AD

Giacobbe Giusti, Odysseus

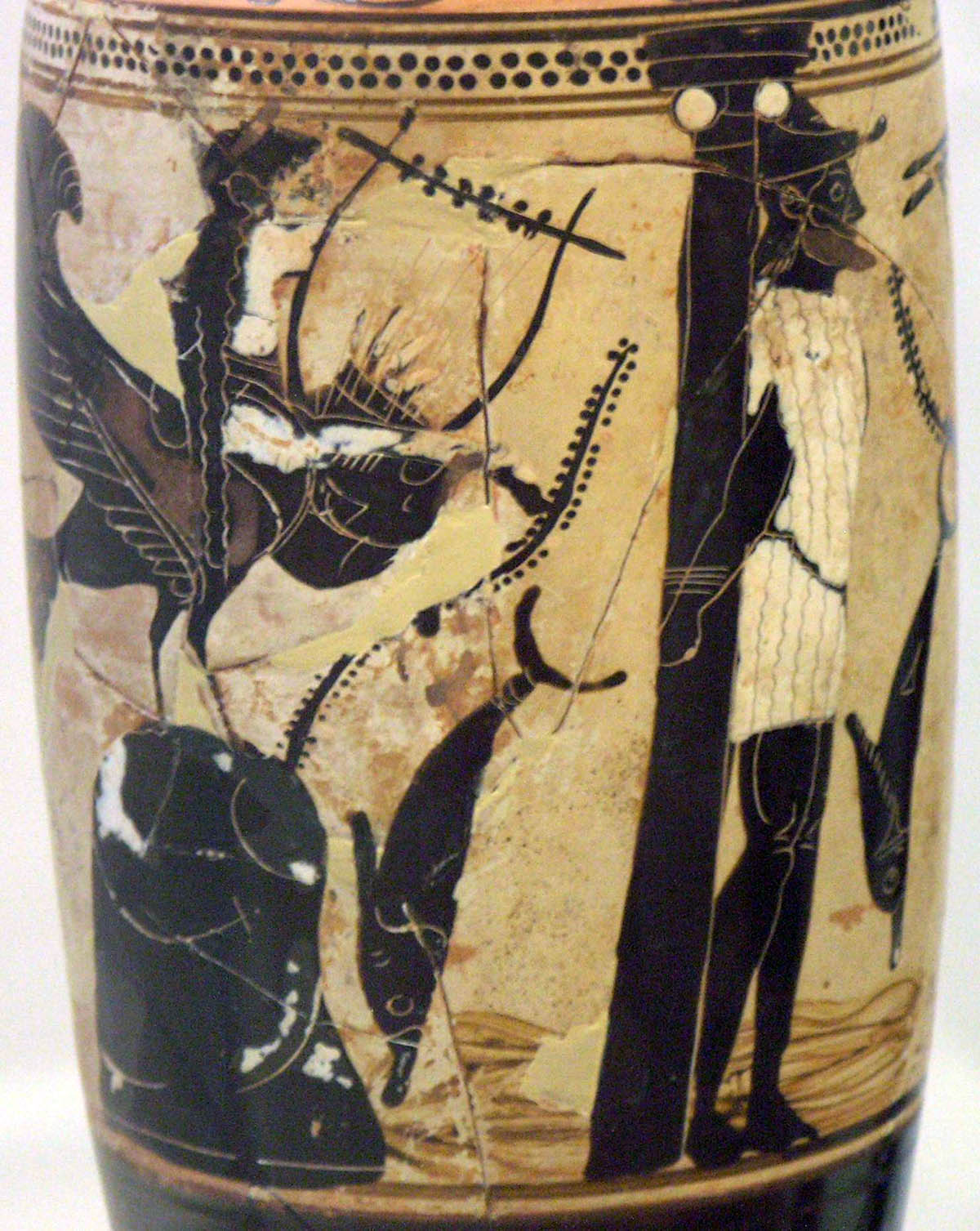

Ulysse lié au mât de son navire pour ne pas céder au chant des sirènes, Musée national archéologique d’Athènes (Inv. 1130)

Giacobbe Giusti, Odysseus

Menelaus and Meriones lifting Patroclus‘ corpse on a cart while Odysseus looks on, Etruscan alabaster urn from Volterra, Italy, 2nd century BC

Giacobbe Giusti, Odysseus

Part of a Roman mosaic depicting Odysseus at Skyros unveiling the disguised Achilles,[30] from La Olmeda, Pedrosa de la Vega, Spain, 5th century AD

Giacobbe Giusti, Odysseus

Ulysse offrant du vin au Cyclope, copie romaine d’un original de la fin de l’époque hellénistique, musée Chiaramonti

| Odysseus

Giacobbe Giusti, Odysseus |

|

|---|---|

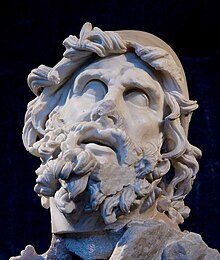

Head of Odysseus from a Roman period Hellenistic marble group representing Odysseus blinding Polyphemus, found at the villa of Tiberius at Sperlonga, Italy

|

|

| Abode | Greece |

| Personal information | |

| Consort | Penelope |

| Children | Telemachus |

| Parents | Laërtes Anticlea |

| Roman equivalent | Ulysses |

| Greek mythology

Giacobbe Giusti, Odysseus |

|---|

|

| Deities |

| Heroes and heroism |

| Related |

Odysseus (/oʊˈdɪsiəs, oʊˈdɪsjuːs/; Greek: Ὀδυσσεύς, Ὀδυσεύς,Ὀdysseús [odysse͜ús]), also known by the Latinvariant Ulysses(US: /juːˈlɪsiːz/, UK: /ˈjuːlɪsiːz/; Latin: Ulyssēs, Ulixēs), is a legendary Greek king of Ithaca and the hero of Homer‘s epic poem the Odyssey. Odysseus also plays a key role in Homer’s Iliad and other works in that same epic cycle.

Son of Laërtes and Anticlea, husband of Penelope and father of Telemachus and Acusilaus.[1] Odysseus is renowned for his intellectual brilliance, guile, and versatility (polytropos), and is thus known by the epithetOdysseus the Cunning (Greek: μῆτις or mētis, “cunning intelligence”[2]). He is most famous for his nostos or “homecoming”, which took him ten eventful years after the decade-long Trojan War.

Name, etymology and epithets

In Greek the name was used in various versions. Vase inscriptions have the two groups of Olyseus (Ὀλυσεύς), Olysseus (Ὀλυσσεύς) or Ōlysseus (Ὠλυσσεύς), and Olyteus (Ὀλυτεύς) or Olytteus (Ὀλυττεύς). Probably from an early source from Magna Graecia dates the form Oulixēs (Οὐλίξης), while a later grammarian has Oulixeus(Οὐλιξεύς).[3] In Latin the figure was known as Ulixēs or (considered less correct) Ulyssēs. Some have supposed that “there may originally have been two separate figures, one called something like Odysseus, the other something like Ulixes, who were combined into one complex personality.”[4] However, the change between d and l is common also in some Indo-European and Greek names,[5] and the Latin form is supposed to be derived from the Etruscan Uthuze (see below), which perhaps accounts for some of the phonetic innovations.

The etymology of the name is unknown. Ancient authors linked the name to the Greek verbs odussomai (ὀδύσσομαι) “to be wroth against, to hate”,[6] to oduromai (ὀδύρομαι) “to lament, bewail”,[7][8] or even to ollumi (ὄλλυμι) “to perish, to be lost”.[9][10] Homer relates it to various forms of this verb in references and puns. In Book 19 of the Odyssey, where Odysseus’ early childhood is recounted, Euryclea asks the boy’s grandfather Autolycus to name him. Euryclea seems to suggest a name like Polyaretos, “for he has much been prayed for” (πολυάρητος) but Autolycus “apparently in a sardonic mood” decided to give the child another name commemorative of “his own experience in life”:[11] “Since I have been angered (ὀδυσσάμενος odyssamenos) with many, both men and women, let the name of the child be Odysseus”.[12] Odysseus often receives the patronymic epithet Laertiades (Λαερτιάδης), “son of Laërtes“. In the Iliad and Odysseythere are several further epithets used to describe Odysseus.

It has also been suggested that the name is of non-Greek origin, possibly not even Indo-European, with an unknown etymology.[13]Robert S. P. Beekes has suggested a Pre-Greek origin.[14] In Etruscan religion the name (and stories) of Odysseus were adopted under the name Uthuze (Uθuze), which has been interpreted as a parallel borrowing from a preceding Minoan form of the name (possibly *Oduze, pronounced /’ot͡θut͡se/); this theory is supposed to explain also the insecurity of the phonologies (d or l), since the affricate /t͡θ/, unknown to the Greek of that time, gave rise to different counterparts (i. e. δ or λ in Greek, θ in Etruscan).[15]

Genealogy

Relatively little is given of Odysseus’ background other than that according to Pseudo-Apollodorus, his paternal grandfather or step-grandfather is Arcesius, son of Cephalus and grandson of Aeolus, while his maternal grandfather is the thief Autolycus, son of Hermes[16]and Chione. Hence, Odysseus was the great-grandson of the Olympian god Hermes.

According to the Iliad and Odyssey, his father is Laertes[17] and his mother Anticlea, although there was a non-Homeric tradition[18][19] that Sisyphus was his true father.[20] The rumour went that Laërtes bought Odysseus from the conniving king.[21] Odysseus is said to have a younger sister, Ctimene, who went to Same to be married and is mentioned by the swineherd Eumaeus, whom she grew up alongside, in book 15 of the Odyssey.[22]

Before the Trojan War

The majority of sources for Odysseus’ pre-war exploits—principally the mythographers Pseudo-Apollodorus and Hyginus—postdate Homer by many centuries. Two stories in particular are well known:

When Helen is abducted, Menelaus calls upon the other suitors to honour their oaths and help him to retrieve her, an attempt that leads to the Trojan War. Odysseus tries to avoid it by feigning lunacy, as an oracle had prophesied a long-delayed return home for him if he went. He hooks a donkey and an ox to his plow (as they have different stride lengths, hindering the efficiency of the plow) and (some modern sources add) starts sowing his fields with salt. Palamedes, at the behest of Menelaus’ brother Agamemnon, seeks to disprove Odysseus’ madness and places Telemachus, Odysseus’ infant son, in front of the plow. Odysseus veers the plow away from his son, thus exposing his stratagem.[23] Odysseus holds a grudge against Palamedes during the war for dragging him away from his home.

Odysseus and other envoys of Agamemnon travel to Scyros to recruit Achilles because of a prophecy that Troy could not be taken without him. By most accounts, Thetis, Achilles’ mother, disguises the youth as a woman to hide him from the recruiters because an oracle had predicted that Achilles would either live a long uneventful life or achieve everlasting glory while dying young. Odysseus cleverly discovers which among the women before him is Achilles when the youth is the only one of them to show interest in examining the weapons hidden among an array of adornment gifts for the daughters of their host. Odysseus arranges further for the sounding of a battle horn, which prompts Achilles to clutch a weapon and show his trained disposition. With his disguise foiled, he is exposed and joins Agamemnon’s call to arms among the Hellenes.[24]

During the Trojan War

The Iliad

Odysseus is one of the most influential Greek champions during the Trojan War. Along with Nestor and Idomeneushe is one of the most trusted counsellors and advisors. He always champions the Achaean cause, especially when others question Agamemnon’s command, as in one instance when Thersites speaks against him. When Agamemnon, to test the morale of the Achaeans, announces his intentions to depart Troy, Odysseus restores order to the Greek camp.[25] Later on, after many of the heroes leave the battlefield due to injuries (including Odysseus and Agamemnon), Odysseus once again persuades Agamemnon not to withdraw. Along with two other envoys, he is chosen in the failed embassy to try to persuade Achilles to return to combat.[26]

When Hector proposes a single combat duel, Odysseus is one of the Danaans who reluctantly volunteered to battle him. Telamonian Ajax, however, is the volunteer who eventually fights Hector. Odysseus aids Diomedes during the night operations to kill Rhesus, because it had been foretold that if his horses drank from the Scamander River, Troy could not be taken.[27]

After Patroclus is slain, it is Odysseus who counsels Achilles to let the Achaean men eat and rest rather than follow his rage-driven desire to go back on the offensive—and kill Trojans—immediately. Eventually (and reluctantly), he consents. During the funeral games for Patroclus, Odysseus becomes involved in a wrestling match and foot race with Ajax “The Lesser,” son of Oileus. With the help of the goddess Athena, who favored him, and despite Apollo‘s helping another of the competitors, he wins the race and draws the wrestling match, to the surprise of all.[28]

Odysseus has traditionally been viewed as Achilles’ antithesis in the Iliad:[29] while Achilles’ anger is all-consuming and of a self-destructive nature, Odysseus is frequently viewed as a man of the mean, a voice of reason, renowned for his self-restraint and diplomatic skills. He is also in some respects antithetical to Telamonian Ajax (Shakespeare’s “beef-witted” Ajax): while the latter has only brawn to recommend him, Odysseus is not only ingenious (as evidenced by his idea for the Trojan Horse), but an eloquent speaker, a skill perhaps best demonstrated in the embassy to Achilles in book 9 of the Iliad. The two are not only foils in the abstract but often opposed in practice since they have many duels and run-ins.

Other stories from the Trojan War

Part of a Roman mosaicdepicting Odysseus at Skyros unveiling the disguised Achilles,[30] from La Olmeda, Pedrosa de la Vega, Spain, 5th century AD

Since a prophecy suggested that the Trojan War would not be won without Achilles, Odysseus and several other Achaean leaders went to Skyros to find him. Odysseus discovered Achilles by offering gifts, adornments and musical instruments as well as weapons, to the king’s daughters, and then having his companions imitate the noises of an enemy’s attack on the island (most notably, making a blast of a trumpet heard), which prompted Achilles to reveal himself by picking a weapon to fight back, and together they departed for the Trojan War.[31]

The story of the death of Palamedes has many versions. According to some, Odysseus never forgives Palamedes for unmasking his feigned madness and plays a part in his downfall. One tradition says Odysseus convinces a Trojan captive to write a letter pretending to be from Palamedes. A sum of gold is mentioned to have been sent as a reward for Palamedes’ treachery. Odysseus then kills the prisoner and hides the gold in Palamedes’ tent. He ensures that the letter is found and acquired by Agamemnon, and also gives hints directing the Argives to the gold. This is evidence enough for the Greeks, and they have Palamedes stoned to death. Other sources say that Odysseus and Diomedes goad Palamedes into descending a well with the prospect of treasure being at the bottom. When Palamedes reaches the bottom, the two proceed to bury him with stones, killing him.[32]

When Achilles is slain in battle by Paris, it is Odysseus and Telamonian Ajax who retrieve the fallen warrior’s body and armour in the thick of heavy fighting. During the funeral games for Achilles, Odysseus competes once again with Telamonian Ajax. Thetis says that the arms of Achilles will go to the bravest of the Greeks, but only these two warriors dare lay claim to that title. The two Argives became embroiled in a heavy dispute about one another’s merits to receive the reward. The Greeks dither out of fear in deciding a winner, because they did not want to insult one and have him abandon the war effort. Nestor suggests that they allow the captive Trojans decide the winner.[33] The accounts of the Odyssey disagree, suggesting that the Greeks themselves hold a secret vote.[34] In any case, Odysseus is the winner. Enraged and humiliated, Ajax is driven mad by Athena. When he returns to his senses, in shame at how he has slaughtered livestock in his madness, Ajax kills himself by the sword that Hector had given him after their duel.[35]

Together with Diomedes, Odysseus fetches Achilles’ son, Pyrrhus, to come to the aid of the Achaeans, because an oracle had stated that Troy could not be taken without him. A great warrior, Pyrrhus is also called Neoptolemus (Greek for “new warrior”). Upon the success of the mission, Odysseus gives Achilles’ armour to him.

It is learned that the war can not be won without the poisonous arrows of Heracles, which are owned by the abandoned Philoctetes. Odysseus and Diomedes (or, according to some accounts, Odysseus and Neoptolemus) leave to retrieve them. Upon their arrival, Philoctetes (still suffering from the wound) is seen still to be enraged at the Danaans, especially at Odysseus, for abandoning him. Although his first instinct is to shoot Odysseus, his anger is eventually diffused by Odysseus’ persuasive powers and the influence of the gods. Odysseus returns to the Argive camp with Philoctetes and his arrows.[36]

Perhaps Odysseus’ most famous contribution to the Greek war effort is devising the strategem of the Trojan Horse, which allows the Greek army to sneak into Troy under cover of darkness. It is built by Epeiusand filled with Greek warriors, led by Odysseus.[37] Odysseus and Diomedes steal the Palladium that lay within Troy’s walls, for the Greeks were told they could not sack the city without it. Some late Roman sources indicate that Odysseus schemed to kill his partner on the way back, but Diomedes thwarts this attempt.

“Cruel, deceitful Ulixes” of the Romans

Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey portray Odysseus as a culture hero, but the Romans, who believed themselves the heirs of Prince Aeneas of Troy, considered him a villainous falsifier. In Virgil‘s Aeneid, written between 29 and 19 BC, he is constantly referred to as “cruel Odysseus” (Latin dirus Ulixes) or “deceitful Odysseus” (pellacis, fandi fictor). Turnus, in Aeneid, book 9, reproaches the Trojan Ascanius with images of rugged, forthright Latin virtues, declaring (in John Dryden‘s translation), “You shall not find the sons of Atreus here, nor need the frauds of sly Ulysses fear.” While the Greeks admired his cunning and deceit, these qualities did not recommend themselves to the Romans, who possessed a rigid sense of honour. In Euripides’ tragedy Iphigenia at Aulis, having convinced Agamemnon to consent to the sacrifice of his daughter, Iphigenia, to appease the goddess Artemis, Odysseus facilitates the immolation by telling Iphigenia’s mother, Clytemnestra, that the girl is to be wed to Achilles. Odysseus’ attempts to avoid his sacred oath to defend Menelaus and Helen offended Roman notions of duty, and the many stratagems and tricks that he employed to get his way offended Roman notions of honour.

Journey home to Ithaca

Odysseus and Polyphemus (1896) by Arnold Böcklin: Odysseus and his crew escape the cyclops Polyphemus.

Odysseus is probably best known as the eponymous hero of the Odyssey. This epic describes his travails, which lasted for 10 years, as he tries to return home after the Trojan War and reassert his place as rightful king of Ithaca.

On the way home from Troy, after a raid on Ismarus in the land of the Cicones, he and his twelve ships are driven off course by storms. They visit the lethargic Lotus-Eaters and are captured by the CyclopsPolyphemus while visiting his island. After Polyphemus eats several of his men, Polyphemus and Odysseus have a discussion and Odysseus tells Polyphemus his name is “Nobody”. Odysseus takes a barrel of wine, and the Cyclops drinks it, falling asleep. Odysseus and his men take a wooden stake, ignite it with the remaining wine, and blind him. While they escape, Polyphemus cries in pain, and the other Cyclopes ask him what is wrong. Polyphemus cries, “Nobody has blinded me!” and the other Cyclopes think he has gone mad. Odysseus and his crew escape, but Odysseus rashly reveals his real name, and Polyphemus prays to Poseidon, his father, to take revenge. They stay with Aeolus, the master of the winds, who gives Odysseus a leather bag containing all the winds, except the west wind, a gift that should have ensured a safe return home. However, the sailors foolishly open the bag while Odysseus sleeps, thinking that it contains gold. All of the winds fly out, and the resulting storm drives the ships back the way they had come, just as Ithaca comes into sight.

After pleading in vain with Aeolus to help them again, they re-embark and encounter the cannibalistic Laestrygonians. Odysseus’ ship is the only one to escape. He sails on and visits the witch-goddess Circe. She turns half of his men into swine after feeding them cheese and wine. Hermes warns Odysseus about Circe and gives him a drug called moly, which resists Circe’s magic. Circe, being attracted to Odysseus’ resistance, falls in love with him and releases his men. Odysseus and his crew remain with her on the island for one year, while they feast and drink. Finally, Odysseus’ men convince him to leave for Ithaca.

Guided by Circe’s instructions, Odysseus and his crew cross the ocean and reach a harbor at the western edge of the world, where Odysseus sacrifices to the dead and summons the spirit of the old prophet Tiresias for advice. Next Odysseus meets the spirit of his own mother, who had died of grief during his long absence. From her, he learns for the first time news of his own household, threatened by the greed of Penelope‘s suitors. Odysseus also talks to his fallen war comrades and the mortal shade of Heracles.

Odysseus and the Sirens, Ulixes mosaic at the Bardo National Museum in Tunis, Tunisia, 2nd century AD

Odysseus’ ship passing between the six-headed monster Scylla and the whirlpool Charybdis, from a fresco by Alessandro Allori (1535–1607)

Returning to Circe’s island, she advises them on the remaining stages of the journey. They skirt the land of the Sirens, pass between the six-headed monster Scylla and the whirlpool Charybdis, where they row directly between the two. However, Scylla drags the boat towards her by grabbing the oars and eats six men.

They land on the island of Thrinacia. There, Odysseus’ men ignore the warnings of Tiresias and Circe and hunt down the sacred cattle of the sun god Helios. Helios tells Zeus what happened and demands Odysseus’ men be punished or else he will take the sun and shine it in the Underworld. Zeus fulfills Helios’ demands by causing a shipwreck during a thunderstorm in which all but Odysseus drown. He washes ashore on the island of Ogygia, where Calypsocompels him to remain as her lover for seven years. He finally escapes when Hermes tells Calypso to release Odysseus.

Odysseus departs from the Land of the Phaeacians, painting by Claude Lorrain (1646)

Odysseus is shipwrecked and befriended by the Phaeacians. After telling them his story, the Phaeacians, led by King Alcinous, agree to help Odysseus get home. They deliver him at night, while he is fast asleep, to a hidden harbor on Ithaca. He finds his way to the hut of one of his own former slaves, the swineherd Eumaeus, and also meets up with Telemachus returning from Sparta. Athena disguises Odysseus as a wandering beggar to learn how things stand in his household.

When the disguised Odysseus returns after 20 years, he is recognized only by his faithful dog, Argos. Penelope announces in her long interview with the disguised hero that whoever can string Odysseus’ rigid bow and shoot an arrow through twelve axe shafts may have her hand. According to Bernard Knox, “For the plot of the Odyssey, of course, her decision is the turning point, the move that makes possible the long-predicted triumph of the returning hero”.[38] Odysseus’ identity is discovered by the housekeeper, Eurycleia, as she is washing his feet and discovers an old scar Odysseus received during a boar hunt. Odysseus swears her to secrecy, threatening to kill her if she tells anyone.

When the contest of the bow begins, none of the suitors is able to string the bow of Apollo but then, after all the suitors have given up, the disguised Odysseus comes along, bends the bow, shoots the arrow, and wins the contest. Having done so, he proceeds to slaughter the suitors (beginning with Antinous whom he finds drinking from Odysseus’ cup) with help from Telemachus and two of Odysseus’ servants, Eumaeus the swineherd and Philoetius the cowherd. Odysseus tells the serving women who slept with the suitors to clean up the mess of corpses and then has those women hanged in terror. He tells Telemachus that he will replenish his stocks by raiding nearby islands. Odysseus has now revealed himself in all his glory (with a little makeover by Athena); yet Penelope cannot believe that her husband has really returned—she fears that it is perhaps some god in disguise, as in the story of Alcmene (mother of Heracles) —and tests him by ordering her servant Euryclea to move the bed in their wedding-chamber. Odysseus protests that this cannot be done since he made the bed himself and knows that one of its legs is a living olive tree. Penelope finally accepts that he truly is her husband, a moment that highlights their homophrosýnē (“like-mindedness”).

The next day Odysseus and Telemachus visit the country farm of his old father Laërtes. The citizens of Ithaca follow Odysseus on the road, planning to avenge the killing of the Suitors, their sons. The goddess Athena intervenes and persuades both sides to make peace.

Other stories

Odysseus is one of the most recurrent characters in Western culture.

Classical

According to some late sources, most of them purely genealogical, Odysseus had many other children besides Telemachus, the most famous being:

- with Penelope: Poliporthes (born after Odysseus’ return from Troy)

- with Circe: Telegonus, Ardeas, Latinus, also Ausonus and Casiphone[39]

- with Calypso: Nausithous, Nausinous

- with Callidice: Polypoetes

- with Euippe: Euryalus

- with daughter of Thoas: Leontophonus

Most such genealogies aimed to link Odysseus with the foundation of many Italic cities in remote antiquity.

He figures in the end of the story of King Telephus of Mysia.

The supposed last poem in the Epic Cycle is called the Telegony and is thought to tell the story of Odysseus’ last voyage, and of his death at the hands of Telegonus, his son with Circe. The poem, like the others of the cycle, is “lost” in that no authentic version has been discovered.

In 5th century BC Athens, tales of the Trojan War were popular subjects for tragedies. Odysseus figures centrally or indirectly in a number of the extant plays by Aeschylus, Sophocles (Ajax, Philoctetes) and Euripides, (Hecuba, Rhesus, Cyclops) and figured in still more that have not survived. In his Ajax, Sophocles portrays Odysseus as a modern voice of reasoning compared to the title character’s rigid antiquity.

Plato in his dialogue Hippias Minor examines a literary question about whom Homer intended to portray as the better man, Achilles or Odysseus.

As Ulysses, he is mentioned regularly in Virgil‘s Aeneid written between 29 and 19 BC, and the poem’s hero, Aeneas, rescues one of Ulysses’ crew members who was left behind on the island of the Cyclops. He in turn offers a first-person account of some of the same events Homer relates, in which Ulysses appears directly. Virgil’s Ulysses typifies his view of the Greeks: he is cunning but impious, and ultimately malicious and hedonistic.

Ovid retells parts of Ulysses’ journeys, focusing on his romantic involvements with Circe and Calypso, and recasts him as, in Harold Bloom‘s phrase, “one of the great wandering womanizers.” Ovid also gives a detailed account of the contest between Ulysses and Ajax for the armour of Achilles.

Greek legend tells of Ulysses as the founder of Lisbon, Portugal, calling it Ulisipo or Ulisseya, during his twenty-year errand on the Mediterranean and Atlantic seas. Olisipo was Lisbon’s name in the Roman Empire. This folk etymology is recounted by Strabo based on Asclepiades of Myrleia’s words, by Pomponius Mela, by Gaius Julius Solinus (3rd century AD), and will be resumed by Camões in his epic poem Os Lusíadas (first printed in 1572).[citation needed]

Middle Ages and Renaissance

Dante Alighieri, in the Canto XXVI of the Inferno segment of his Divine Comedy (1308–1320), encounters Odysseus (“Ulisse” in Italian) near the very bottom of Hell: with Diomedes, he walks wrapped in flame in the eighth ring (Counselors of Fraud) of the Eighth Circle (Sins of Malice), as punishment for his schemes and conspiracies that won the Trojan War. In a famous passage, Dante has Odysseus relate a different version of his voyage and death from the one told by Homer. He tells how he set out with his men from Circe’s island for a journey of exploration to sail beyond the Pillars of Hercules and into the Western sea to find what adventures awaited them. Men, says Ulisse, are not made to live like brutes, but to follow virtue and knowledge.[40]

After travelling west and south for five months, they see in the distance a great mountain rising from the sea (this is Purgatory, in Dante’s cosmology) before a storm sinks them. Dante does not have access to the original Greek texts of the Homeric epics, so his knowledge of their subject-matter was based only on information from later sources, chiefly Virgil‘s Aeneid but also Ovid; hence the discrepancy between Dante and Homer.

He appears in Shakespeare‘s Troilus and Cressida (1602), set during the Trojan War.

Modern literature

The bay of Palaiokastritsa in Corfu as seen from Bella vista of Lakones. Corfu is considered to be the mythical island of the Phaeacians. The bay of Palaiokastritsa is considered to be the place where Odysseus disembarked and met Nausicaa for the first time. The rock in the sea visible near the horizon at the top centre-left of the picture is considered by the locals to be the mythical petrified ship of Odysseus. The side of the rock toward the mainland is curved in such a way as to resemble the extended sail of a trireme.

Alfred, Lord Tennyson‘s poem “Ulysses” (published in 1842) presents an aging king who has seen too much of the world to be happy sitting on a throne idling his days away. Leaving the task of civilizing his people to his son, he gathers together a band of old comrades “to sail beyond the sunset”.

Frederick Rolfe‘s The Weird of the Wanderer (1912) has the hero Nicholas Crabbe (based on the author) travelling back in time, discovering that he is the reincarnation of Odysseus, marrying Helen, being deified and ending up as one of the three Magi.

James Joyce‘s novel Ulysses (first published 1918–1920) uses modern literary devices to narrate a single day in the life of a Dublin businessman named Leopold Bloom. Bloom’s day turns out to bear many elaborate parallels to Odysseus’ ten years of wandering.

In Virginia Woolf’s response novel Mrs Dalloway (1925) the comparable character is Clarisse Dalloway, who also appears in The Voyage Out (1915) and several short stories.

Nikos Kazantzakis‘ The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel (1938), a 33,333 line epic poem, begins with Odysseus cleansing his body of the blood of Penelope‘s suitors. Odysseus soon leaves Ithaca in search of new adventures. Before his death he abducts Helen, incites revolutions in Crete and Egypt, communes with God, and meets representatives of such famous historical and literary figures as Vladimir Lenin, Don Quixote and Jesus.

Return to Ithaca (1946) by Eyvind Johnson is a more realistic retelling of the events that adds a deeper psychological study of the characters of Odysseus, Penelope, and Telemachus. Thematically, it uses Odysseus’ backstory and struggle as a metaphor for dealing with the aftermath of war (the novel being written immediately after the end of the Second World War).

Odysseus is the hero of The Luck of Troy (1961) by Roger Lancelyn Green, whose title refers to the theft of the Palladium.

In 1986, Irish poet Eilean Ni Chuilleanain published “The Second Voyage”, a poem in which she makes use of the story of Odysseus.

In S. M. Stirling‘s Island in the Sea of Time (1998), first part to his Nantucket series of alternate history novels, Odikweos (“Odysseus” in Mycenaean Greek) is a ‘historical’ figure who is every bit as cunning as his legendary self and is one of the few Bronze Age inhabitants who discerns the time-travellers’ real background. Odikweos first aids William Walker’s rise to power in Achaea and later helps bring Walker down after seeing his homeland turn into a police state.

The Penelopiad (2005) by Margaret Atwood retells his story from the point of view of his wife Penelope.

The literary theorist Núria Perpinyà conceived twenty different interpretations of the Odyssey in a 2008 study.[41]

Television and film

The actors who have portrayed Odysseus in feature films include Kirk Douglas in the Italian Ulysses (1955), John Drew Barrymore in The Trojan Horse (1961), Piero Lulli in The Fury of Achilles (1962), and Sean Bean in Troy (2004).

In TV miniseries he has been played by Bekim Fehmiu, L’Odissea(1968), and by Armand Assante, The Odyssey (1997).

Ulysses 31 is a French-Japanese animated television series (1981) that updates the Greek mythology of Odysseus to the 31st century.[42]

Joel and Ethan Coen‘s film O Brother Where Art Thou? (2000) is loosely based on the Odyssey. However, the Coens have stated that they had never read the epic. George Clooney plays Ulysses Everett McGill, leading a group of escapees from a chain gang through an adventure in search of the proceeds of an armoured truck heist. On their voyage, the gang encounter—amongst other characters—a trio of Sirens and a one-eyed bible salesman.

Odysseus is also a character in David Gemmell‘s Troy trilogy (2005–2007), in which he is a good friend and mentor of Helikaon. He is known as the ugly king of Ithaka. His marriage with Penelope was arranged, but they grew to love each other. He is also a famous storyteller, known to exaggerate his stories and heralded as the greatest storyteller of his age. This is used as a plot device to explain the origins of such myths as those of Circe and the Gorgons. In the series, he is fairly old and an unwilling ally of Agamemnon.

Music

The British group Cream recorded the song “Tales of Brave Ulysses” in 1967. Suzanne Vega‘s song “Calypso” from 1987 album Solitude Standing shows Odysseus from Calypso‘s point of view, and tells the tale of him coming to the island and his leaving.

Comparative mythology

Over time, comparisons between Odysseus and other heroes of different mythologies and religions have been made.

Nala

A similar story exists in Hindu mythology with Nala and Damayantiwhere Nala separates from Damayanti and is reunited with her.[43] The story of stringing a bow is similar to the description in Ramayana of Rama stringing the bow to win Sita‘s hand in marriage.[44]

Aeneas

The Aeneid tells the story of Aeneas and his travels to what would become Rome. On his journey he also endures strife comparable to that of Odysseus. However, the motives for both of their journeys differ as Aeneas was driven by this sense of duty granted to him by the Gods that he must abide by. He also kept in mind the future of his people, fitting for the future Father of Rome.

Namesakes

Prince Odysseas-Kimon of Greece and Denmark (born 2004), is the grandson of the deposed Greek king, Constantine II.

Notes

- ^ Epic Cycle. Fragments on Telegony, 2 as cited in Eustathias, 1796.35.

- ^ “μῆτις – Liddell and Scott’s Greek-English Lexicon”. Perseus Project. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Entry “Ὀδυσσεύς” at Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott, A Greek–English Lexicon, 1940.

- ^ Stanford, William Bedell (1968). The Ulysses theme. A Study in the Adaptability of a Traditional Hero. New York: Spring Publications. p. 8.

- ^ See the entry “Ἀχιλλεύς” in Wiktionary; cfr. Greek δάκρυ, dákru, vs. Latin lacrima “tear”.

- ^ Entry “ὀδύσσομαι” in Liddell and Scott, A Greek–English Lexicon.

- ^ Entry “ὀδύρομαι” in Liddell and Scott, A Greek–English Lexicon.

- ^ Helmut van Thiel, ed. (2009). Homers Odysseen. Berlin: Lit. p. 194.

- ^ Entry “ὄλλυμι” in Liddell and Scott, A Greek–English Lexicon.

- ^ Marcy George-Kokkinaki (2008). Literary Anthroponymy: Decoding the Characters in Homer’s Odyssey (PDF). 4. Antrocom. pp. 145–157. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- ^ Stanford, William Bedell (1968). The Ulysses theme. p. 11.

- ^ Odyssey 19.400–405.

- ^ Dihle, Albrecht (1994). A History of Greek Literature. From Homer to the Hellenistic Period. Translated by Clare Krojzl. London and New York: Routledge. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-415-08620-2. Retrieved 4 May2017.

- ^ Robert S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, Leiden 2009, p. 1048.

- ^ Glen Gordon, A Pre-Greek name for Odysseus, published at Paleoglot. Ancient languages. Ancient civilizations. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- ^ Apollodorus, Bibliotheca Library 1.9.16

- ^ Homer does not list Laërtes as one of the Argonauts.

- ^ Scholium on Sophocles‘ Aiax 190, noted in Karl Kerényi, The Heroes of the Greeks, 1959:77.

- ^ “Spread by the powerful kings, // And by the child of the infamous Sisyphid line” (κλέπτουσι μύθους οἱ μεγάλοι βασιλῆς // ἢ τᾶς ἀσώτου Σισυφιδᾶν γενεᾶς): Chorus in Ajax 189–190, translated by R. C. Trevelyan.

- ^ “A so-called ‘Homeric’ drinking-cup shows pretty undisguisedly Sisyphos in the bed-chamber of his host’s daughter, the arch-rogue sitting on the bed and the girl with her spindle.” The Heroes of the Greeks 1959:77.

- ^ “Sold by his father Sisyphus” (οὐδ᾽ οὑμπολητὸς Σισύφου Λαερτίῳ): Philoctetes in Philoctetes 417, translated by Thomas Francklin.

- ^ “Women in Homer’s Odyssey”. Records.viu.ca. 16 September 1997. Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae 95. Cf. Apollodorus, Epitome 3.7.

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae 96.

- ^ Iliad 2.

- ^ Iliad 9.

- ^ Iliad 10.

- ^ Iliad 23.

- ^ D. Gary Miller (2014 ), Ancient Greek Dialects and Early Authors, De Gruyter ISBN 978-1-61451-493-0. pp. 120-121

- ^ Documentation on the “Villa romana de Olmeda”, displaying a photograph of the whole mosaic, entitled “Aquiles en el gineceo de Licomedes” (Achilles in Lycomedes‘ ‘seraglio’).

- ^ Achilleid, book 1.

- ^ Apollodorus, Epitome 3.8; Hyginus 105.

- ^ Scholium to Odyssey 11.547.

- ^ Odyssey 11.543–47.

- ^ Sophocles, Ajax 662, 865.

- ^ Apollodorus, Epitome 5.8.

- ^ See, e.g., Odyssey 8.493; Apollodorus, Epitome 5.14–15.

- ^ Bernard Knox (1996): Introduction to Robert Fagles‘ translation of The Odyssey, p. 55.

- ^ John Tzetzes. Chiliades, 5.23 lines 568-570

- ^ Dante, Divine Comedy, canto 26: “fatti non-foste a viver come bruti / ma per seguir virtute e conoscenza”.

- ^ Núria Perpinyà (2008): The Crypts of Criticism: Twenty Readings of The Odyssey (Spanish original: Las criptas de la crítica: veinte lecturas de la Odisea, Madrid, Gredos).

- ^ Ulysses 31 webpage

- ^ Wendy Doniger (1999). Splitting the difference: gender and myth in ancient Greece and India. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-15641-5. pp. 157ff

- ^ Harry Fokkens; et al. (2008). “Bracers or bracelets? About the functionality and meaning of Bell Beaker wrist-guards”. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. University of Leiden. 74. p. 122.

References

- Vasil S. Tole (2005). Odyssey and Sirens: A Temptation towards the Mystery of the Iso-polyphonic Regions of Epirus. A Homeric theme with variations. Tirana, Albania. ISBN 99943-31-63-9.

- Robert Bittlestone; James Diggle; John Underhill (2005). Odysseus Unbound: The Search for Homer’s Ithaca. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-85357-5.(www.odysseus-unbound.org)

- Ernle Bradford (1963). Ulysses Found. Hodder and Stoughton.

- “Archaeological discovery in Greece may be the tomb of Odysseus” from the Madera Tribune

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Odysseus“. Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Odysseus“. Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press